Are Teachers in Trouble?

Research on teachers’ mental health points to high rates of distress, but a deeper understanding is needed

What is the relationship between the emotional load of teachers’ work and individual manifestations of illness? We need to document and address clinical needs – such as pain, functional impairment, mental illness and social isolation– that go deeper than simple “wellness programs.”

I first heard about the National Standard for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace in 2017.

That year, I was part of a small delegation of teachers who were attending (for the very first time) the Nova Scotia Federation of Labour Biennial Convention in Halifax, N.S. Of all the amazing insights I gained that weekend, learning about directly connecting workplace stress to worker wellness was a key moment for me.

The “Standard” was originally launched in 2013. Supported by the Mental Health Commission of Canada, it is a set of voluntary guidelines, tools and resources designed to help organizations prevent psychological injury at work. The standard aims to connect overall worker wellness with more tangible ideas like stress and workplace absenteeism.

As a union leader, my job centres around helping teachers navigate the increasingly complex world of public education. Naturally, my perception of that complexity is coloured by my role.

My phone seldom rings when teachers are doing well, and my phone is seldom quiet for very long.

However, I am also keenly aware that the angst I witness in my own members is not limited to my one small corner of the world.

The global educational landscape is littered with stories of teacher shortages and excessive attrition rates.

As I read more about psychological wellness, I began to question the frequently cited but hard to define platitudes often used to describe teachers in crisis. Words like “stress” and “burnout” are frequently associated with the teaching profession, but they are hard to pin down. The terms still have an almost ephemeral ring to them, much like PTSD used to. (PTSD – post-traumatic stress disorder – struggled for years for definition, let alone acceptance.) I began to look for research, any research, that explored the connections between the stress being felt by teachers in the classroom and their overall health. Much to my chagrin, my searches were fruitless.

“Students’ and teachers’ healthy minds and bodies are critical to quality public education.”

Then, in another fortunate turn of fate, I met MSVU researcher Dr. Krista Ritchie, Assistant Professor at Mount Saint Vincent University and a scientist at the IWK Health Centre in Halifax. Her program of research makes connections across the fields of education and health. Through a multitude of research projects and collaborations over time, she has formed a strong commitment to applied research for the public good, framed by the central tenet that healthcare is an education issue and education is a healthcare issue.

According to Ritchie, opportunities for clinicians, patients and care providers to learn about illness and new evidence-informed treatments are critical to quality healthcare. Similarly, students’ and teachers’ healthy minds and bodies are critical to quality public education. One of the keys to being able to approach this applied research effectively is the willingness to establish meaningful and trusting collaboration across stakeholders. As such, she has sought to collaborate with community groups, schools, hospitals, and most recently the Nova Scotia Teachers’ Union (NSTU).

NSTU President Paul Wozney says, “Ninety-one hundred NSTU members have expressed a clear desire to partner in research that illuminates the growing struggle teachers experience with mental health, and with mental health issues that develop due to workload and the evolving complexity of their jobs.” They view research as a way to delineate the negative impact mental health issues have on their personal wellness, vital relationships and ability to do their jobs. They voted in overwhelming support of this action at our Annual Council in 2018; our board of directors subsequently approved a proposal from Dr. Krista Ritchie to undertake collaborative research to this end.

If your organization, school district or faculty of education is an EdCan member (see the list here), you can enjoy unlimited access to our online content! Click here to create your online account.

Through this most recent collaboration, a team approach is being used to identify a way to do high quality research that explores the relationship between the emotional load of teachers’ work and individual manifestations of illness. This includes such things as pain, functional impairment, mental illness, and social isolation.

Perhaps most importantly, the research attempts to find ways in which these factors influence the nuanced decisions teachers make every day that shape student learning and engagement.

Certainly, what statistics we do have indicate a clear need for further examination of the impact of wellness on the classroom.

Canadian statistics indicate that approximately 25 percent of adults experience mental illness at some point.

Statistics Canada estimates that 4.8 percent of adult Canadians have depression.

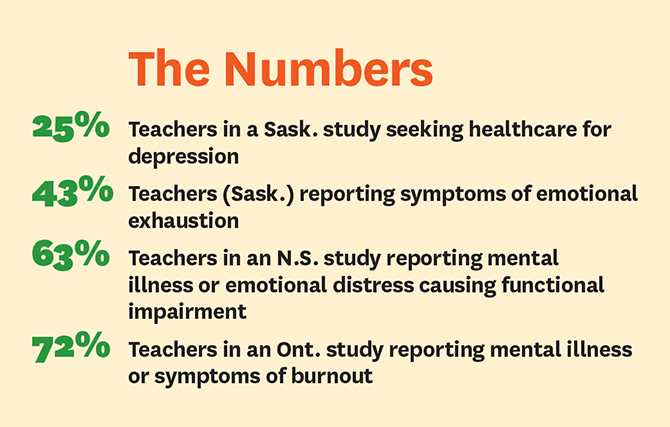

When it comes to the teaching profession, a 2012 report revealed that 25 percent of 745 teachers interviewed in Regina and Saskatoon were seeking healthcare for depression and 43 percent reported symptoms of emotional exhaustion.1

A thesis recently published from Western University reported that 72 percent (almost 3 in 4) of surveyed teachers identified as having either mental illness or symptoms of burnout resulting from stress, such as avoidance strategies and social disengagement.2

Here in N.S., Dr. Ritchie and the NSTU have partnered on an ongoing study of public school teachers.

Initial analysis of the data collected so far indicates that 63 percent of surveyed teachers reported that they currently have mental illness or emotional distress resulting in functional impairment of work and home responsibilities. Of these respondents with illness or distress, 71 percent reported that their health problems were interfering with their normal social activities with friends, family, neighbours, or social groups.

This is concerning because social support is a protective factor against mental illness.

Although it is too early to draw strong conclusions about whether teachers are experiencing higher rates of mental illness than the national average, these studies tell us that we need to be asking the question and generating valid and reliable prevalence rates.

This area of research could be of tremendous value in directly informing healthcare needs and program planning for teachers. To even begin to consider the potential impact on students, we must generate population level statistics that can guide provincial and national conversations.

Who helps the helpers?

It is equally important to situate these statistics in the teaching and learning contexts where students are learning every day. As part of the effort to meet that goal, Ritchie has been joined by Laura Leslie, a St. Francis Xavier University PhD student. Leslie comes to her PhD studies with over 15 years’ experience as a teacher in Nova Scotia schools, and with a background in counselling. Her research interests are in the impact of trauma on students and schools – an interest sparked by her own experiences as a classroom teacher supporting students affected by traumatic and adverse life events. Community violence, illness, loss, poverty, abuse, witnessing or experiencing frightening events are just some of the experiences that can have a significant impact on children in our schools.

During her years of teaching these students, Leslie came to recognize how supporting students with trauma was affecting the health of her teaching colleagues. She found herself going to the empirical literature and asking the question “Who helps the helpers?”3

That question is one that is thankfully starting to be asked more often. New research is revealing the prevalence of secondary trauma symptoms in educators in today’s classrooms. Further research is needed to understand and support teachers with these ongoing, daily and often pervasive challenges.

“Psychological health in the workplace needs to become a major focus across the educational landscape of our nation.”

Within the teaching profession, we bear witness daily to human flourishing. Seeing students learn to read, gain independence and learn about themselves is a great privilege. This privilege is situated in trusting relationships with children – those very individuals upon whom society places so much value. Yet within the ranks of those charged with their care and academic development, there exists long documented evidence of high attrition rates, particularly among early-career teachers.4

Psychological health in the workplace needs to become a major focus across the educational landscape of our nation. These efforts need to move beyond simple wellness programs that, although helpful, do not compare to documenting health needs that must be addressed by healthcare professionals.

Whether it be among classroom teachers, university academics, community members or educational leadership, collaboration in addressing this issue will be key.

We all do better by reaching across institutions and working together to generate high quality and relevant evidence to solve real problems.

Photo: iStock

First published in Education Canada, March 2020

Notes

1 R. R. Martin, R. Dolmage, and D. Sharpe, Seeking Wellness: Descriptive findings from the survey of the work life and health of teachers in Regina and Saskatoon (Saskatchewan Teachers’ Federation, Saskatoon, SK, 2012). www.stf.sk.ca/sites/default/files/seeking_wellness.pdf

2 K. Marko, “Hearing the Unheard Voices: An in-depth look at teacher mental health and wellness,” (Thesis, University of Western Ontario, London, ON, 2015), 2-15

3 H. A. Lawson, J. C. Caringi, R. Gottfried, B. E. Bride, and S. P. Hydon, “Educators’Secondary Traumatic Stress, Children’s Trauma, and the Need for Trauma Literacy,” Harvard Educational Review 89, no. 3 (2019): 421–447.

4 L. Darling-Hammond, “The Challenge of Staffing our Schools,” Educational Leadership58, no.8 (2001): 12-17; B. Kutsyuruba, L. Godden and L. Tregunna, Early-career Teacher Attrition and Retention: A pan-Canadian document analysis study of teacher induction and mentorship programs (Kingston, ON: Queen’s University, 2013).