Cultivating Well-Being

A systems approach

The stress that teachers experience has many sources. Teachers often report feeling undervalued, underprepared, unsupported, overworked, isolated, and marginalized. A Canadian Teachers’ Federation (2014) survey found that eight in ten teachers feel their stress levels have increased over the previous five years. Reasons cited for elevated stress levels include an inadequate amount of preparation time, limited opportunities for planning and collaboration with colleagues, lack of professional development opportunities, and insufficient support with curriculum implementation. Stress impacts teacher well-being, social emotional competence, and the ability of teachers to provide the emotional and instructional support that is characteristic of safe, caring, learning environments.1

When educators experience burnout, the emotional exhaustion that sets in can negatively impact teacher instruction and elevate student stress levels, leading to further mental health issues in the classroom.2 Teacher burnout can cause students to perceive the classroom as negative, which can lead to increased behavioural problems – and it is problem behaviours that teachers cite as a major source of job dissatisfaction, turnover, and lowered expectations. In Canada, stress and burnout has contributed to the high number (25 to 30 percent) of teachers who leave the field entirely within the first five years of beginning their career.3

A district-wide model for supporting teacher well-being

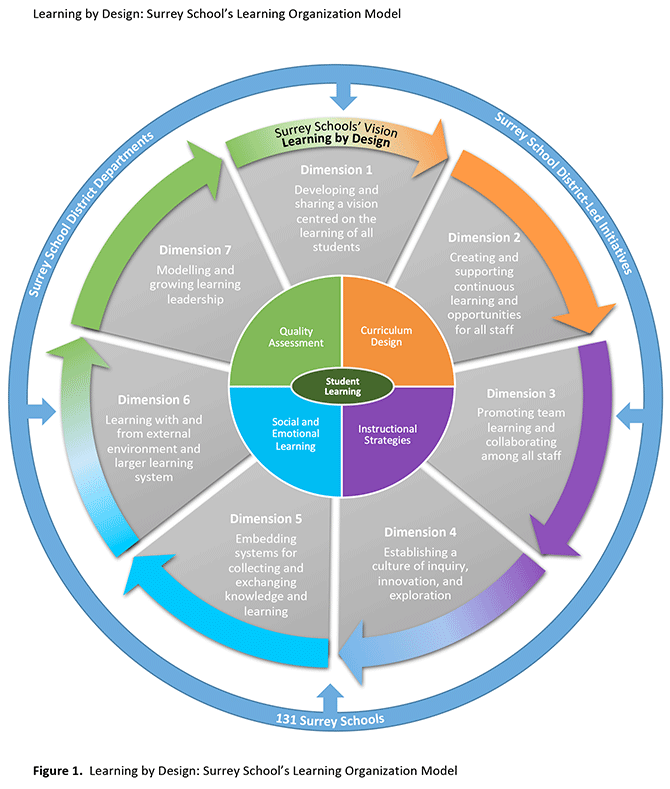

The OECD (2016) has conceptualized an integrated School as Learning Organization model4 with seven key dimensions, described in Figure 1 below. The Surrey School District (SD 36) has developed and implemented a district-wide shared vision for learning – Learning by Design – that puts into action each of the OECD dimensions.

A key aspect of Learning by Design is our commitment to supporting ongoing professional learning through research, innovation, and collaboration as part of our four Priority Practices:

- Curriculum Design that deepens learning and supports students in gaining important core competencies

- Quality Assessment that focuses on the learning process and provides multiple opportunities for students to demonstrate their learning

- Instructional Strategies that are carefully crafted by teachers to enrich learning experiences for all students

- The implementation and support of quality Social and Emotional Learning through research-based processes and practices.

Below we describe a collection of district-wide initiatives, aligned with our four Priority Practices that promote educator well-being, self-efficacy, and connectedness. These initiatives were underpinned by research into best practices, and designed and implemented by multi-department teams. Within our systems change approach, we have in place formalized research, monitoring, and evaluation activities to ensure program challenges are identified and addressed.

Strategies for supporting teacher well-being

Social Emotional Learning for educators When educators demonstrate social emotional competencies (SEC), it translates into positive impacts on teacher-student relationships, a healthier classroom climate, greater student Social Emotional Learning (SEL) and academic achievement, and implementation of more effective SEL and classroom management strategies. Research finds that teachers high in SEC tend to have lower levels of workplace stress, a greater sense of personal accomplishment and satisfaction in their career, and are often better able to provide emotional and instructional support to students.5

Providing professional development grounded in SEL for educators not only provides them with skills to improve their own mental well-being and emotional resiliency, it also provides them with tools to take those skills and implement them with the learners in their schools.

The Surrey Schools’ SEL for Educators (SEL4E) initiative has been offering a series of workshops that provide educators with tools to increase their SEC by developing:

- A greater sense of self-awareness and teacher efficacy

- Mindfulness practices that support teacher well-being

- Increased emotional resilience

- Self-compassion in teaching and learning.

Educators who took part in this initiative reported that they have the confidence to bounce back from a challenging day due to a better understanding of SEL practices, that the skills they learned will support them in overcoming challenges in their career, and that they can identify, assess, and implement strategies that will support their SEC and resiliency.

A district of our size faces barriers to offering SEL professional development opportunities on a wide scale. While it’s great that we have many requests from school staff to take part in SEL4E, the number of requests often exceed what our resources will allow. The district is committed to increase capacity and provide for more collaborative and experiential learning opportunities.

Supporting an SEL climate in schools Educational research finds that system-wide approaches can contribute to improved social emotional competencies for student populations and school staff.6 The Surrey SEL Initiative is a school-wide systems approach to integrating academic, social, and emotional learning (SEL) across the district as a means to promote equitable outcomes for all students, while also promoting teacher wellness and resiliency.

To fuse SEL practices at the level of a school community, our approach incorporates capacity building, collaboration, and reflection on the pedagogical practices teachers adopt and implement in their classrooms. It uses resources from the CASEL Guide to School-wide Social and Emotional Learning to support our schools in assessing the SEL climate of the student population and staff, and to guide planning and monitoring of implemented SEL programs and activities.

Teachers and administrators form a school-based SEL Team and participate in a collaborative process, supported by the District SEL Team. Each school receives release time for one teacher (SEL Lead) one day per week to support the implementation of quality SEL practices. The SEL Lead works side-by-side with classroom teachers in their school to co-plan and co-facilitate the implementation of SEL-based curriculum to enhance learners’ skills development.

This model builds on relationships that exist within a staff. While changes in staff are always the concern, we have found that the nature of this work is taking root and proving sustainable beyond one individual. Evaluation efforts are currently underway to better understand the impacts of the Surrey SEL initiative and the sort of district supports that are needed at all levels of the school system.

Comprehensive mentoring support Mentor 36 is a joint initiative between Surrey Schools (SD 36) and the Surrey Teachers’ Association. It aims to foster a sustained culture of collaborative mentorship at every site in Surrey, supporting professional growth and a sense of belonging for Surrey teachers, through strength-based, non-evaluative learning opportunities such as:

- Ongoing professional learning sessions for teachers who are in the first five years of the profession and new to the role

- Ongoing professional learning for mentors/facilitators

- Peer-to-peer support and collaborative cohorts.

Currently, Mentor 36 has 91 elementary mentors and 126 elementary mentees, as well as 136 secondary mentors and 110 secondary mentees. Feedback data revealed that the majority of mentees (59 percent) were comfortable sharing their vulnerabilities and discussing instructional strategies with their own mentors. About two-thirds of mentors (67%) felt they had developed a safe and trusting mentoring relationship, as evidenced by their mentees reaching out and connecting, feeling comfortable and safe to ask for support, and discussing classroom issues.

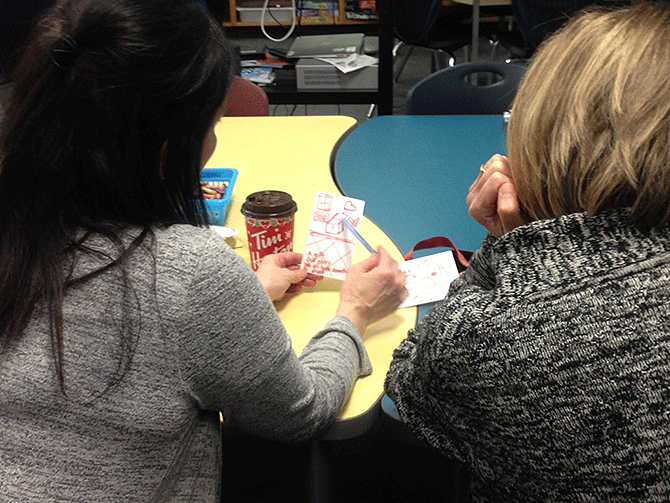

At a Mentor Learning Session, mentors created a collaborative drawing depicting the benefits of teacher mentorship.

Collaboration time and efficacy building as strategies to address stress

A review of best practices by the Centre for the Use of Research Evidence in Education7 finds that collaboration that enables co-learning, co-development, and joint work for educators is linked to improved professional knowledge, skills and practices, and increased expectations for student learning. Increased collaboration and communication between teachers often both reduces feelings of isolation and improves teachers’ knowledge and skills. These in turn lead to lower teacher burnout and greater feelings of capability to meet challenges in the classroom.8

Two of Surrey’s programs to support students also support teacher wellness by providing opportunities to collaborate and share learning to better meet the needs of specific students:

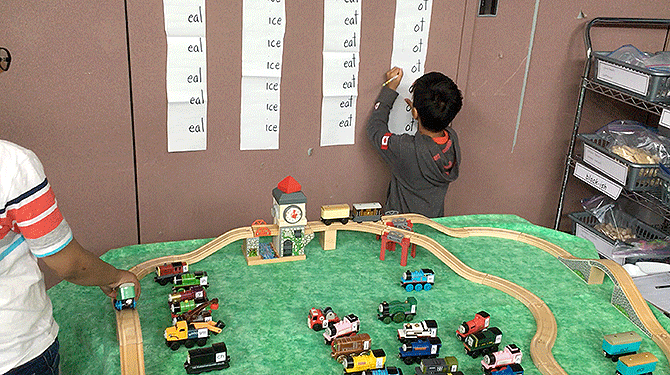

The Inner-City Early Learning initiative provides early literacy and numeracy support for “at-promise” students in Kindergarten and Grade One who may be demonstrating challenges in literacy and/or numeracy development since the 2012-2013 academic year. Specialist teachers in literacy and numeracy work collaboratively with classroom teachers in 26 inner-city schools.

Grade One students collaborate to build (with onset-rime trains) and record words with the support of their Early Literacy Teacher.

These early literacy and numeracy supports have provided a success story for our inner-city schools. One challenge is that only three of the original 25 early literacy and early numeracy teachers from the 2012-2013 start-up are still with the program. This rate of turnover impacts the professional capacity building of the department as a whole, and it is more difficult to maintain connections and trust when relationships between early learning support staff and classroom teachers have to begin anew each school year. Despite these challenges, this initiative continues to successfully support some of the district’s most vulnerable learners.

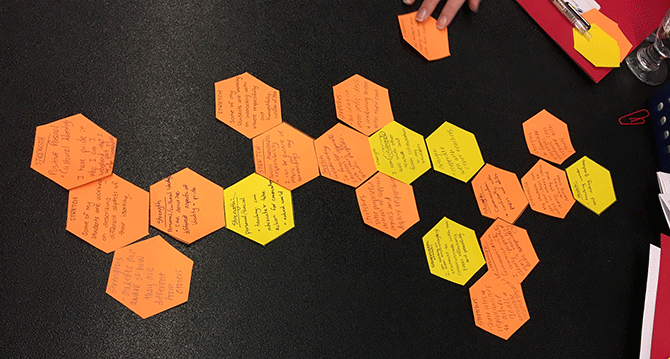

The Knowing Our Learners Initiative offers School Teams (teachers and administrators) the opportunity to participate in Knowing Our Learners (KOL), a collaborative initiative that aims at enhancing instructional and assessment practices with the support of Curriculum and Instructional Helping Teachers. This year, 175 teachers in 55 schools participated in this program, which focuses on knowing our learners’ stories, strengths and challenges, and using this knowledge to design effective learning environments that keep social and emotional well-being, quality assessment, and evidence of learning at the heart of every child’s learning experience.

KOL activities led to teachers feeling supported and more aware of ways to align their learning intentions with student needs and to make informed decisions about teaching strategies and interventions based on research and other supports. Beyond the impacts KOL sessions had on teacher practices, the initiative was grounded in teacher-to-teacher relationships, open dialogue, and peer reflections. KOL was effective because it was “situated in relationships.” As one participant commented, KOL sessions “made me feel working with [my colleague] made me more [sensitive to] what is working and what’s not. I felt it improved our capacity to know how each other worked to help students.”

Knowing our Learners Honeycomb Activity: Teachers wrote and made connections of strengths and stretches of their own Core Competencies with those of their students.

Sustainability challenges and the road ahead

While many Surrey schools have embraced the initiatives previously discussed, maintaining motivation and engagement year over year can be challenging. Additionally, while we have found school-wide buy-in for many sites, in some instances only pockets of teachers have been engaged in these collaborative opportunities. We are working toward overcoming these challenges by ensuring rigorous research and evidence collection activities are embedded throughout each initiative, in order to make adjustments for future planning of district-led initiatives. Our process and outcomes-based program evaluations are formative in nature, grounded in best practices in evaluation designs, and include the stories and reflections of school staff.

The district also ensures that participation in its professional learning opportunities is predicated on school staff either forming or being part of a team at their school site (e.g. SEL School-based Teams). This can still pose a challenge when team members bring to the initiative different goals and competencies on which they wish to focus. We address these differences by connecting Helping Teachers and teacher mentors with specific school sites to help facilitate team discussions and bring clarity around the team’s goals and activities.

With a district focus on social and emotional learning, we are addressing not only the health and well-being of students, but of our teachers as well. We believe that healthy and capable teachers foster healthy school classrooms and give students the best possible chances for success. Surrey School’s Learning by Design framework reflects our systems approach to cultivating well-being. By building teachers’ SEL competencies, we are able to address teacher burnout and stress, support teacher wellness, elevate teacher autonomy and voice, and build resiliency through cross-departmental collaborations.

The primary authors wish to recognize contributions from: Gloria Sarmento (Director of Instruction, Building Professional Capacity Department), Taunya Shaw (District Helping Teacher, Social and Emotional Learning), Courtney Jones (District Helping Teacher, Inner City Early Learning Support), and Sharon Lau (District Helping Teacher, Mentoring)

Illustration: iStock

Photos: Courtesy authors

First published in Education Canada, September 2020

Notes

1 M. T. Greenberg, J. L. Brown, and R. M. Abenavoli, Teacher Stress and Health: Effects on teachers, students, and schools, (Edna Bennett Pierce Prevention Research Center and Pennsylvania State University, 2016).

2 Schonert-Reichl, “Social and Emotional Learning and teachers,” The Future of Children, 27, 137-155.

3 P. A. Jennings and M. T. Greenberg, “The Prosocial Classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes,” Review of Educational Research 79 (2009): 491-525.

4 OECD, What Makes A School a Learning Organisation? A guide for policy makers, school leaders and teachers, (Paris: OECD, 2016).

5 K. A. R. Richards, C. Levesque-Bristol, T. J. Templin, and K. C. Graber, “The Impact of Resilience on Role Stressors and Burnout in Elementary and Secondary Teachers,” Social Psychology of Education 19 (2016): 511-536.

6 G. G. Bear, S. A. Whitcomb, M. J. Elias, and J. C. Blank, J. C. (2015). “SEL and Schoolwide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports,” in Handbook of Social and Emotional Learning: Research and practice (New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2015).

7 CUREE, Understanding What Enables High-Quality Education: A report on the research evidence (London: Pearson Education, 2016).

8 Richards et al., “The Impact of Resilience on Role Stressors and Burnout in Elementary and Secondary Teachers.”