Sexual and Gender Minorities in Canadian Schools

Sexual and Gender Minorities in Canadian Schools

I still live with hurtful memories of being a timid and apprehensive gay boy who was bullied mercilessly and suffered immense mental anguish during junior and senior high school. I was subjected to incessant name calling and targeted by packs of boys on school buses and school grounds. Later, as a teacher, I was perpetually in fear of being outed as gay and losing my job. I dealt with unrelenting stressors, like finding pictures of naked men left under wiper blades on my car windshield in the school parking lot. These indelible memories are my impetus for wanting to make life better now for sexual and gender minorities (SGMs or LGBTQ2+ persons) in our schools. In Canada today, there is an established basis for doing this, bolstered by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Since the Supreme Court of Canada decision in Vriend v. Alberta in 1998, which granted equality rights to sexual minority Canadians, there have been continuous changes in law, legislation, and educational policy that have abetted recognizing and accommodating SGMs in school culture and curriculum. More recently, Bill C-16, An Act to Amend the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Criminal Code, which became law in 2017, provided gender minorities with protection against discrimination on the grounds of gender identity and expression.

With such movement forward, what is it like for SGMs to have SGM-specific policy in place in our schools as social spaces where students learn and teachers work? I took up this question in research1 I conducted in a large urban school district in western Canada that had had a standalone SGM policy, rather than merely an umbrella or general equity policy, in place for five years. Having SGM-specific policy is far from the norm in school districts in our country, so I interviewed key interest groups that included students and teachers to learn about their experiences. Students were asked to discuss everyday stressors and supports as they talked about school culture, climate, curriculum, principals, and teachers. Teachers were asked to discuss the importance of having SGM policy and practice that impact the recognition, accommodation, and well-being of SGMs. Here, I share some of their perspectives.

Students’ perspectives: What teachers do matters

The high-school students I interviewed commonly spoke about the need to educate others about SGMs and our issues and concerns. One student who was president of his high-school GSA (Gay-Straight Alliance or Gender-Sexuality Alliance) spoke pragmatically about this:

“I think having more education would be helpful because when people are uneducated, they don’t like what they don’t understand or what they don’t perceive to be normal. I think having education is a really big aspect. Incorporating LGBTQ+ case studies into courses would be really helpful.”

Another high-school student spoke about her former faith-based school where sexual orientation was still a taboo topic. She related, “It was never spoken about. There were no comments on it, and anything you did to try to bring it up, they’d put you down.” She spoke positively about the SGM-inclusive culture in her current school, stating, “I find it very welcoming. You see same-sex couples in the hallway, and there’s nothing – nobody blinks an eye.” She spoke about the teachers, saying, “One of my friends had a teacher who used their preferred pronouns and names. So that’s one teacher I know who’s very accepting. I’m pretty sure there are multiple other teachers who would as well. On the first day, they read off the attendance list and, of course, that’s your legal name. But if you ask, there are multiple teachers who will use the student’s preferred name and pronouns.” Another high school student also spoke about the naming issue, using an example to indicate how students can be negatively impacted in a public way: “One thing that sucks is for Valentine’s Day, they do the hearts. They write everyone’s name on a heart and put them in the lunchroom downstairs. But because they use the attendance list to do it, it’s birth names and legal names. So that can cause anxiety.” One trans-identified student who uses he/him pronouns provided this particular concern regarding naming and roll call. He recounted, “A big issue that you need to work with is substitute teachers. My legal name and the name that I go by are not the same, so I always need to talk to the substitutes ahead of time. That’s a bit stressful. Sometimes they forget. They always try, but you can’t remember everything.” Regarding his teachers in general, this student pondered, “I wish there was some way for the teachers to understand how significant it is to respect pronouns and labels and titles because I feel like some of them don’t understand some of the consequences. The first few times don’t bother you that much, but the more it happens, the more it bothers you. Most of my teachers don’t seem to understand how much it affects me. It makes me feel crappy.” Like other students I interviewed, this student spoke about the need to educate teachers:

“I feel because teachers are directly interacting with and impacting queer youth, it should be part of training them on a PD day or something, just to take a crash course on understanding. I don’t know if those things do happen or what the situation is with that. I just wish in general that people knew more about us and just the facts and less of the perceptions. I don’t know specifically what would be available to them, though. I do wish there was more information that was commonly known. Overall, I think our teachers are pretty supportive – some more than others – just because they’re more educated on everything. And some really try to learn with you, which is helpful. They want you to tell them stuff that they don’t know. There’s still a lot of improvements that can be made, a lot more information that can be shared. With more knowledge, there’s less misunderstanding, there’s less judgment, and everybody can just live together more peacefully and not be angry at each other or confused.”

Teachers’ perspectives: Knowing school culture, being an advocate

Supportive teachers I interviewed saw schools as social spaces where they engaged in strategic actions to advance SGM inclusion. One high-school teacher provided this perspective on what constituted an SGM-inclusive culture in her school:

“The school is very welcoming and comprehensive in terms of how staff accept students and how students themselves are perceived around the school. There isn’t a lot of discussion that we have to do because the SGM policy dictates behaviour. It’s more about creating a culture: We’ll do it because that’s what people do. This results in fewer students seeking out the GSA on a regular basis because the culture of the school itself is so open and accepting that everywhere is a safe place. The school encounters zero parent resistance to pink shirt day and other GSA events. The administration is very vocally supportive of the students wherever they are in their identity journey. They want to put those students first, ahead of any reservations of parents or complaints from community members. Everyone realizes that comfort is not covered under our provincial human rights legislation, but lack of discrimination and the ability to exist in your identity are covered.”

Of course, creating a genuinely accepting SGM-inclusive school culture takes time. Another high school teacher spoke about his GSA work to help non-heterosexual boys become more comfortable with their sexual identities: “In the GSA, it’s always more girls than guys – substantially. It’s probably 80 percent girls and 20 percent boys, if not lower. I’ve talked to other GSA teachers, and they’ve seen the same thing. Many times, I’ve heard girls say that they felt safe. I haven’t really heard a boy commenting either way. Maybe that’s why fewer boys come to the GSA meeting. There generally is more of a stigma for them, especially in high schools.” Paralleling this perspective on non-heterosexual boys’ discomfort, another high school teacher provided this observation: “I don’t think I’ve ever seen any boys holding hands, but I’ve seen lots more girls holding hands – girlfriends. That’s now just as okay as heterosexual couples walking down the hallway.” A junior high school teacher offered a similar perspective, indicating it is not just a high-school issue: “The girls seem to be far more comfortable at the junior high age for sure compared to the boys. Absolutely, I don’t think boys are quite there yet at this stage, which is sad. It’s unfortunate.”

Many teachers spoke to the importance of having a standalone school district policy on sexual orientation and gender identity to fortify the work to create an SGM-inclusive school culture. In this regard, one teacher working in an all-grades setting provided her perspective on living out this policy in word and action:

“It’s about a district level of support that starts with leadership. It’s about letting all staff know that it’s about not having prejudice and discrimination based on a student’s perceived or actual sexual orientation or gender identity. It’s about being appropriate with our responses as a staff if we encounter that, whether it’s in behaviours, comments, or the actions of other students. But it goes so much deeper. It’s in the way you would group students, in washroom use and locker use, in language use in the classroom, and in resources and approaches. So, it’s really helpful in building on safe and caring schools. It gives us something to work toward so we’re all consistent. We have a policy and we have the support of our district to continue to do that.”

In sum, teachers provided an array of reasons why a standalone SGM policy is a good thing. One high-school teacher saw it as assurance enabling SGM inclusion when teachers couldn’t rely on the school principal. He concluded, “Putting a policy on this was a good thing because you’re not always going to have an understanding administrator, a forward-thinking administrator.” A junior high school teacher felt the policy enabled him to start a GSA, which subsequently contributed to more SGM inclusion in his school. He said, “I’ve had students say how much better it is in the school since we started the GSA. I used to hear students say, ‘That’s so gay’ – constantly. I can’t even remember the last time I had to say something to a student about that. It’s just known that that’s not acceptable to do anymore. Those sorts of things to do with language and what’s acceptable in schools – I think a lot of that has to do with the policy.”

A standalone SGM policy that is consistently implemented… is a clear indicator that a school district has the backs of SGM teachers and allied teachers.

Considering whether the standalone policy made a difference for teachers in her district, a teacher working in a K-12 school responded, “I think by our surety that we’ve got our backs covered, that makes us stronger in what we’re trying to achieve.” She also saw the policy as effective in assisting SGM students who require basic accommodation that includes having their physical needs met: “I know last year, one student would go home to go to the bathroom. Of course, they wouldn’t come back. Washroom access is something so simple and so painful at the same time.”

Supporting SGM teachers, creating an SGM-inclusive school

Increasingly today, young SGM teachers choose to be vocal and visible at work, which is enabled when there is policy in place to protect them. However, many SGM teachers in our country still navigate homophobia and transphobia in their schools. Their challenges and concerns are well documented in The Every Teacher Project on LGBTQ Inclusive Education in Canada’s K-12 Schools.2

Importantly, a gay junior high school teacher spoke about the significance of having the policy in terms of SGM teacher welfare:

“I think it’s fantastic. I think it’s awesome. When it got put in place in our school district, it just seemed quite far advanced from where the rest of the province was. Just being able to know you’ve got the backing of the board is huge. Knowing that you can go in and ask these questions and do these things and not be petrified is massive. Not that it ever felt like there was a lot of homophobia in my district. I know people have encountered pockets of it here and there. I know of some horror stories, but I came out in my second year as a teacher. It was never a big deal, but it’s still nice to know that the board has your back.”

Indeed, having a standalone SGM policy that is consistently implemented and periodically reviewed is a clear indicator that a school district has the backs of SGM teachers and allied teachers engaged in SGM-inclusive work. Such specific policy can nurture an SGM-positive school culture and encourage principals to lead the way in being there for SGM students and teachers. In the end, policy is protection and its purposeful implementation is true recognition and accommodation of SGM students and teachers.

In terms of being there for SGM teachers, here are three constructive ways to be accommodative: First, show support. Notably, having strong support from school leaders can create a more open dialogue and space whereby SGM teachers feel safe to deliver and engage in SGM-inclusive education. Second, develop inclusive workplace policies. At the school district level, standalone anti-homophobia and anti-transphobia policies covering SGM staff and students – rather than generic equity policy – should stand alongside workplace harassment policies and be implemented to protect and support SGM staff. Third, create a professional and/or informal network. SGM teachers within the district can form a professional GSA where they meet to share their experiences, learn from one another, and develop trusting and supportive professional relationships.

As well, teachers – including SGM teachers needing mentors – students, principals, and parents can learn from the good work that openly LGBTQ+ educators do. Here is an excerpt from an interview I conducted with an openly gay elementary school principal in the school district who spoke about his work to be a change agent and advocate in his school:

“What do I do at my school? Certainly, we have our safe-contact teachers identified. We also have the safe and caring rainbow stickers. There’s one right as you enter the school, and there’s one on my office door, my assistant principal’s door, and on the classroom doors of the safe contact teachers and other supportive teachers. I’ve had many conversations with my parent council around the work we’re doing in order to have their support for the SOGI [sexual orientation and gender identity] work in our school. Our library collection is also growing as we find more and more stories that depict the LGBTQ+ youth and their families and same-sex families. I also have conversations with my staff about heteronormativity, the gender spectrum, and the language we use with students. So, is it working? I certainly know that my staff is very aware. Also, my sexuality is not hidden from my staff, so my staff know who I am. I also let them know that my partner is male and he’s a grade one teacher. I do it because I want them to know that I believe in the normalization of sexuality and gender in our schools, that it is no big deal. It is just who we are.”

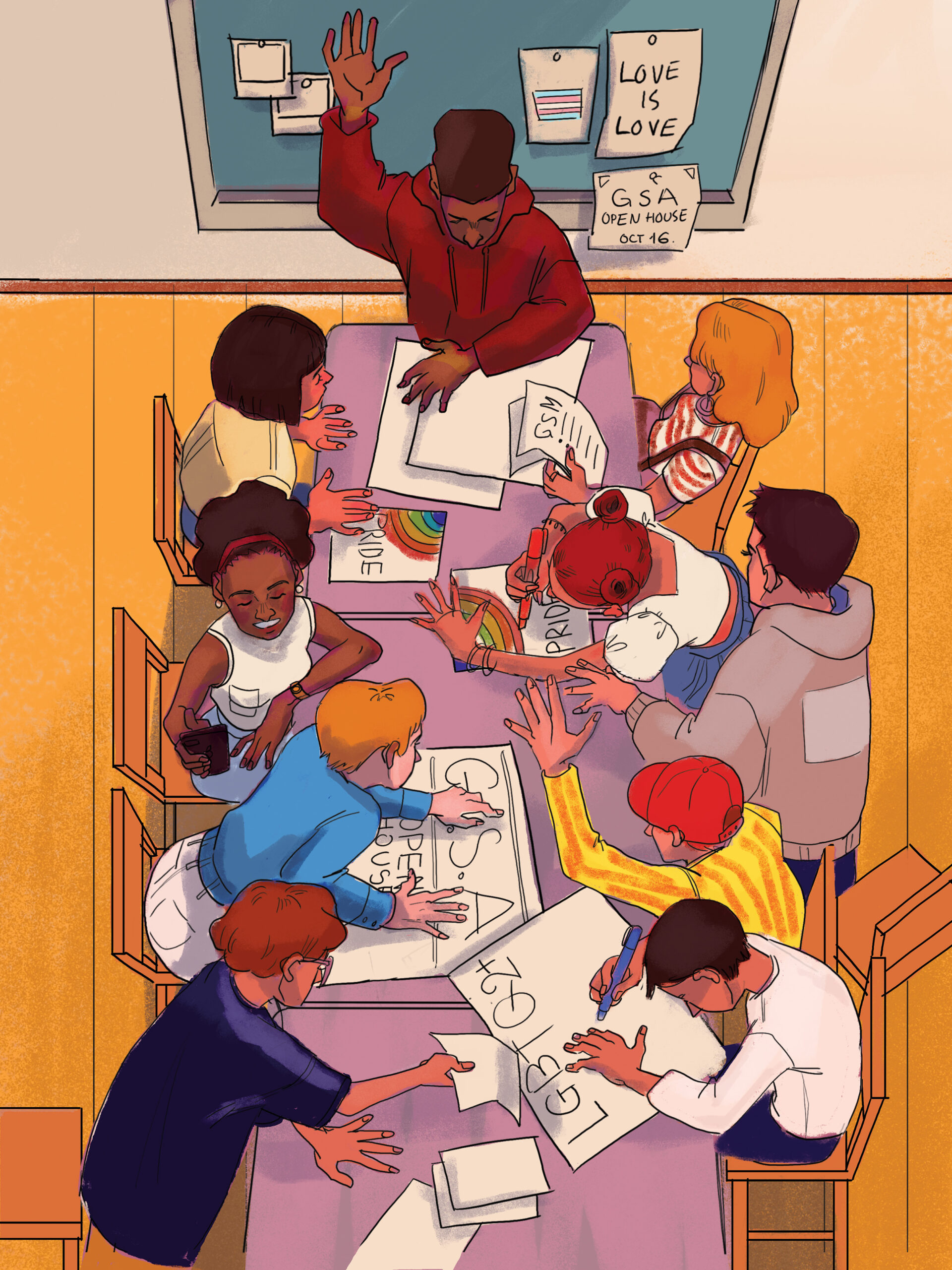

Illustration: Diana Pham

First published in Education Canada, September 2020

Notes

1 The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada funded this research.

2 C. Taylor, T. Peter, C. Campbell, et al., The Every Teacher Project on LGBTQ-inclusive Education in Canada’s K-12 Schools: Final report (Winnipeg, MB: Manitoba Teachers’ Society, 2015). http://egale.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Every-Teacher-Project-Final-Report-WEB.pdf