Mentoring Pre Service Teachers – Everybody wins

Associate teaching is a reciprocal learning experience

This article introduces preliminary research exploring associate teachers’ visions of their learning within the mentorship experience.

DO YOU REMEMBER the first time you rode a two-wheeler?

After months or years of watching others do it, the magical moment finally arrives when you actually pedal on your own! For pre-service teachers, this moment usually occurs during their practicum placement. Many teacher candidates view this time when they first put theory into practice as the most important component of their teacher education program.1 An essential feature of the practicum experience is the guidance and support provided by the associate teacher. Associate teachers (also known as mentor teachers, host teachers or cooperating teachers) are experienced teachers who model effective teaching practices and provide feedback to advance the development of teacher candidates.2 This guidance steadies teacher candidates as they test and apply their developing knowledge, allowing them to actively advance their praxis.3

Teaching, of course, is far more complex than riding a bicycle. However, the two are similar in that neither can be learned through mere observation or passive reception of instructions. The learning is both in the doing and in the analysis of what was done. The core of an effective practicum experience is the process of gaining an understanding of what works and what doesn’t work, first by doing and then by altering what was done based on observation and collaborative reflection.

But it is not only the pre-service teacher who learns from this experience. Anyone who has ever taught another person a skill can attest that the act of breaking down a concept in order to explain it requires the explainer to carefully examine his or her own understanding. This also holds true for guiding and examining practice with someone who is learning to teach.

Research on learning through mentoring

The voices of associate teachers heard through research speak of playing a variety of roles, including coach, model, confidante and critical friend. Increasingly, teachers and researchers are recognizing that associate teachers also play the role of co-learner. In fact, reciprocal learning was ranked as the “most beneficial aspect” of being an associate teacher in a survey of 134 teachers working with teacher candidates in an Ontario faculty of education.4 Several researchers have established that learning during the mentoring relationship is a two-way street; both mentee and mentor learn from the collaborative relationship.5 Much of this work examines associate teaching in general, identifying reciprocal learning as an incidental benefit of the mentoring experience. The potential of these two-way learning relationships has yet to be fully explored.

In my work as a practicum facilitator for a Bachelor of Education program that specializes in developing French as a Second Language (FSL) teachers, I regularly ask associate teachers if they are interested in continuing their work with teacher candidates. The responses below are typical:

« J’aimerais bien participer encore l’année prochaine dans votre programme de formation. Les TCs avec lesquels j’ai travaillé ces derniers jours m’ont donné beaucoup de bonnes idées et ils ont invigoré [sic] mon programme. »

Author’s translation:

I would like to continue next year with the teacher education program. The teacher candidates with whom I have worked recently have given me many good ideas and have invigorated my program.

« J’aimerais bien continuer à accueillir des stagiaires dans ma classe. J’adore la collaboration. J’ai un “growth mindset” et chaque expérience . . . est une ouverture pour m’améliorer. »

Author’s translation:

I would like to continue welcoming teacher candidates into my classroom. I have a growth mindset and each experience . . . is an opportunity for self-improvement.

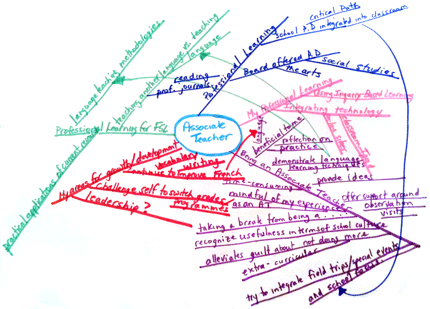

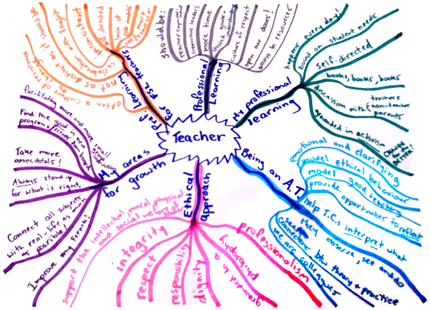

The enthusiasm of these associate teachers inspired me to explore the more intentional application of mentorship experiences within the context of professional learning. Teachers who contributed to the pilot of an ongoing research project created the mind maps that accompany this article. The maps show the teachers’ vision of their associate teaching experience as it relates to own professional learning.

“Mind Map A” shows that the teacher has identified integrating “school PD into classroom practice” as part of her continued professional learning. She links this to her work with teacher candidates, with an arrow from the top to the bottom of the map, noting that as an associate teacher, she has and will “try to integrate… school focus” into her work with the teacher candidate. This associate teacher also highlights her professional learning experiences specific to teaching FSL, and links this learning to areas she will reinforce with the teacher candidate. She identifies continued improvement of her use of French as an area for growth and links her pursuit of this goal to her work with the teacher candidate.

“Mind Map B” shows that the second associate teacher has also identified a need to improve upon her use of the target language. Like the creator of Mind Map A, this teacher connects addressing the language-related learning goal to her work as an associate teacher. Language teachers who teach a language that is not widely used in the local community frequently find it challenging to maintain or advance their language skills. Working with a teacher candidate provides the opportunity to use the target language with another fluent adult speaker. The creator of Mind Map B also identifies the fact that her work as an associate teacher calls upon her to “model good teaching” and “ethical behaviour.” Associate teachers who have participated in other research studies have identified this heightened sense of responsibility due to being observed by the teacher candidate as a source of professional learning.6 Such modeling of “good teaching” may also advance this teacher towards growth in her self-identified area of need: “recording more anecdotal observations.”

Enhancing professional learning

How might you access the reciprocal learning that associate teaching can bring to your teaching practice? A first step would be simply to recognize the potential of mentoring as a professional learning experience. You can then enhance the experience through documentation and reflection. Identify areas of your own practice that you would like to advance, and then think about the links between these goals and your work as an associate teacher. From there, you can develop a plan that may include:

- consciously modeling effective practice for the teacher candidate and highlighting self-identified areas for growth;

- including the teacher candidate in your implementation of school/board/ministry initiatives;

- exploring new resources and practices through co-planning and co-teaching with the teacher candidate;

- purposefully reflecting on challenges and “aha moments” during the practicum experience and linking them to present and future practice.

Continued professional learning is a widely held standard of practice for the teaching profession, with provinces and territories across Canada requiring teachers to complete some form of professional learning plan. Alberta is one province that underscores the role of associate teaching in this context, noting that the annual teacher professional growth plan “may consist of a planned program of supervising a student teacher or mentoring a teacher.”7 Other jurisdictions provide frameworks for teachers to develop professional learning in which they may include associate teaching.8

ONE OF THE MANY benefits of situated professional learning within the practicum is the advancement of experienced teachers’ practice through reflection, modeling and inquiry. Identification of these growth opportunities enables associate teachers to set measurable goals for themselves within the mentorship experience and gain formal recognition for their learning. Increased awareness of the reciprocal learning that takes place within mentoring relationships builds the teaching and learning capacity of teachers at every stage of their career.

First published in Education Canada, March 2015

[i] Clive Beck and Clare Kosnick, “Components of a good practicum placement: Student teacher perceptions,” Teacher Education Quarterly 29, no. 2 (2002): 81-98.

[ii] Ontario College of Teachers, Additional Qualification Course Guideline: Associate teaching, Schedule C teachers’ qualifications regulation (Toronto: Ontario College of Teachers Standards of Practice and Accreditation Department, 2011).

[iii] Praxis: the synthesis of theory and practice.

[iv] Karen Roland, Associate Teacher Feedback: Anonymous & confidential questionnaire (research report, Windsor, ON: University of Windsor, 2009).

[v] Melody Russell and Jared Russell, “Mentoring Relationships: Cooperating teachers’ perspectives on mentoring student interns,” The Professional Educator 35, no. 1 (2011): 6.

[vi] Daniel McCloy, “Learning Teaching: Reciprocal learning,” (PhD diss., Arizona State University, 2011); Andrew Hobson, P. Ashby, A. Malderez and P. Tomlinson, “Mentoring Beginning Teachers: What we know and what we don’t,” Teaching and Teacher Education 25, no. 1 (2009): 207-216.

[vii] http://education.alberta.ca/department/policy/otherpolicy/teacher.aspx

[viii] Ontario, Alberta and Yukon are among the jurisdictions that explicitly acknowledge mentoring as a PD activity.