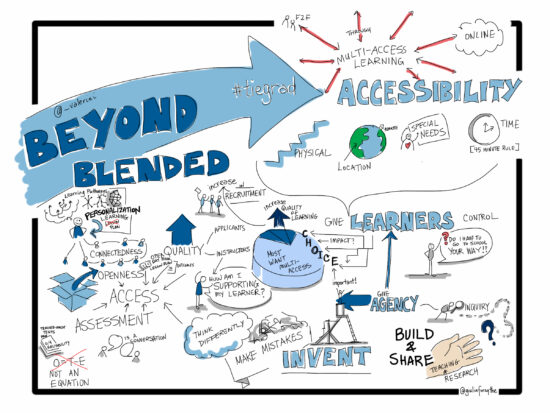

Why NOT to Quit After First Attempts in Online and Hybrid Learning

Exploring the intersection and biases around pedagogy, modality, and access in schools

G. Forsythe, licensed by CC BY NC SA 2.0

*Click on the image to view full-screen

There’s no return to pre-pandemic teaching. We must accept the reality that the need for flexibility is endemic in the K–12 education system.

Without question, teachers, educational administrators, staff, and learners have been run through the gauntlet since the pandemic created sudden and massive shifts to how we teach. These shifts were executed without preparation, without supports, and – for many – while also juggling family commitments while working from home. It makes sense that, through fatigue and frustration, some may want to return to pre-pandemic teaching as quickly as possible. However, in looking at how we will teach in a post-pandemic world, we must examine the privileges and biases that existed in the pre-pandemic school system and resist perpetuating them. We have an incredible opportunity to transform our systems and our practices.

In this article, I’ll review the intersection between pedagogy, modality (i.e. online or face-to-face), and access, explore commonly held biases, and argue that the K–12 sector needs to stay the course – not in repeating how things were done during the pandemic, but in iterating to new and improved ways that support teachers, learners, and educational staff in offering a more socially just and equitable school system.

Modality and equity

As we shift back into a post-pandemic era, how can we teach in a way that ensures access and flexibility for all learners? We were able to pivot an entire system on short notice. Surely, we can embrace inclusion and human rights so as not to abandon those who still remain marginalized and require flexibility when we return.

Ultimately, whenever we pick a modality, we marginalize a learner. When we choose to offer face-to-face-only classes with rigid schedules, we fail to support learners who require flexibility – whether it is to self-regulate and control anxiety or their response to trauma by not being in a classroom a full five days a week, or to get relief from a two-hour commute to the nearest school. Many learners require frequent medical appointments or recovery time for health issues, while others require flexibility for family travel or sport programs. In contrast, when we choose to offer online programs, we may assume the learner has access to the internet at home or the technology to access the course. The design might also require significant parental support, which may not be possible. Which learner has the right to be served within their local community school? Why does one learner get supported in their local context, while the other is asked to leave their community?

Ultimately, we need to support all modalities to implement an inclusive and socially just education system. How we do it requires careful consideration, so it is not burdening the teacher to be a full-time, in-person teacher, while also engaged in online synchronous and asynchronous activities. Both modes can be designed and delivered well, but require some reorganization of roles within a school or district. For example, British Columbia’s School District 69 Qualicum Restart Plan (n.d.) for the 2020/21 school year, hired three teachers assigned to two classrooms in elementary (offering both in-person and remote learning) and cross-enrolled secondary learners in both their home school and the district’s online learning programs. This district supported and retained learners, when other districts forced them into home schooling or out-of-district online programs.

We were able to pivot an entire system on short notice. Surely, we can embrace inclusion and human rights so as not to abandon those who still remain marginalized and require flexibility when we return.

Choosing not to engage technology or not to engage different modes of access results in exclusion for many learners. There are also other considerations, however, such as the loss of funding to a school or district, and loss of teacher jobs, which happens when learners leave a school or district in favour of homeschooling or an online school with a higher teacher-student ratio.

And they do leave. BCEdAccess, an organization serving families of learners with disabilities, released 2020 study findings that support the need for flexibility. In 2021, they documented family intentions to leave the system and found that 67.5% of 453 respondents’ children attended in-person public school in the 2019/20 year. That number dropped to 43.9% in the 2020/21 post-pandemic school year. During the same period, they reported that enrolment increased in other schooling alternatives, with the most frequent being:

- Independent online learning, up 12.1%

- Public online learning, up 7.1%

- Registered homeschooling, up 1.6%

- Hybrid and remote learning, up 1.5%

Both during and pre-pandemic, many students have been pushed out of their local catchment schools and into homeschooling or online programs that are often out of district or private. By not providing flexible and online designs within schools, we are essentially defunding the public school system, reducing teacher jobs, and abandoning learners who need access to education and inclusion in their community school. The irony is that not providing adequate funding and online designs may have cost the system more in accumulated losses. While the indirect impact on the greater economy is hard to measure, learner exclusion from school has a severe impact on working parents – most often mothers – and sometimes results in loss of employment. We need to address systemic gender inequity in how we design both our workplaces and our schools.

Types of Modality Explained

- Multi-access learning: a mix of modes, including a concurrent mix of face-to-face and online learners connecting synchronously via video, and asynchronous connection. The extent to which a learner has freedom to choose their mode varies. For example, there may be a required synchronous portion and required asynchronous participation.

- HyFlex: a type of multi-access learning with full learner autonomy to choose. However, few courses offer full choice due to learning design and workload considerations.

- Blended synchronous or synchronous hybrid: multi-access learning that involves the synchronous mixing of face-to-face and online learners via video.

- Blended or hybrid learning: a consecutive mix of face-to-face and online learning, with all learners being required to participate in each mode. (The term “hybrid” has been misused to refer to both concurrent and consecutive mixing of online and face-to-face components, making it unclear to learners what is expected of them.)

- Online learning: learning that happens fully online. This label is no longer sufficient on its own as learners need to know whether it is synchronous only, a blend of synchronous and asynchronous learning, or asynchronous only.

For more on the landscape of merging modalities, see my EDUCAUSE Review article (Irvine, 2020a).

Modality bias

Since online learning emerged decades ago out of text-based asynchronous learning, we have a historical bias to address: namely, that online learning is passive while face-to-face learning is rich and dynamic. It is key, however, to separate the pedagogy from the modality. The pedagogy applied within a mode will determine whether the learning experience is dynamic or passive (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: A Modality-Pedagogy Matrix

Graphic and bottom right photo: Valerie Irvine, CC BY 4.0. Other photos: UnSplash.

A growing body of research concludes that one learning mode is not necessarily better than the other. The no-significant difference phenomenon is well documented, and the famous Clark vs. Kozma debate on whether media impacts learning is distilled in a blog post by elementary vice-principal, Emily Miller. Clark and Feldon (2014) conclude that “studies comparing the learning benefits of different media are a waste of resources.” Instead, they argue, what’s needed is “many more research and evaluation studies focused on the use of media to improve student access to instructional programs and to reduce the cost of learning” (p. 153). (See Open Educational Resources.)

Open Educational Resources

Integrating technology-based education can also reduce the cost of learning. This cost savings can be realized through shared services and resource creation by both teachers and learners through Creative Commons licenses. Open licensing empowers sharing and remixing to suit local contexts, and can also reduce costs by averting the purchase of corporate for-profit resources. The post-secondary sector has begun embracing open educational resources (OER) to lower textbook costs for students – $20 million in 2020 in B.C. alone (BCcampus). Moving beyond open textbooks into OER-enabled pedagogy (Wiley, 2017) can help K–12 discover, reuse, remix, and co-create Canadian and locally developed resources.

We also need to recognize that learners hold different preferences about modality. In my study of preservice teachers enrolled in a core teacher education course offered in multi-access format, with a required synchronous component, learners varied widely when ranking their preferred modality (Irvine et al., 2013). After having taken the course, the rank order across participants was:

- multi-access learning in the face-to-face group

- blended learning

- multi-access learning in the synchronous online video group

- face-to-face

- online.

Note that the lowest-ranked modes were the binaries of face-to-face and online learning. Most learners preferred a more flexible mix of the two. Various factors influence one’s preference or need for modality (e.g. need for geographic relocation, physical and mental health, length of commute, caregiving, prior experience with different modes, etc.) and preferences may differ across contexts and time periods. If those needs do not match the rigid scheduling of K–12 community schools, it puts additional stress on the student to adapt.

Unfortunately, in many K–12 online schools, it is the opposite extreme: learners are often able to enroll continuously throughout the year and follow different paces asynchronously through learning modules, which results in additional stress for the teacher and potentially poor scaffolding or community-building for the learner. There needs to be a compromise, with a proper needs assessment study of both learners and teachers.

The path forward

We need to ask ourselves why the learners in many online classes do not have the same opportunities as their face-to-face peers in terms of class ratio, design, relational learning, and supports. It is important to address the modality bias that exists around supports required for both online and face-to-face learning. For example, we can and should build inquiry-based learning strategies into our online offerings. We need approaches that focus more on the learner and on co-creating the curriculum, as opposed to course shells literally purchased from a company in Texas. Regardless of mode, the role of the teacher and the conditions around class sizes and supports are the same. Quality learning, whether face-to-face or online, is built around relationships and care-centred approaches for the learner.

Moving beyond the haphazard “emergency remote teaching” era and embracing the integration of technology and online modes will take a concerted effort, through professional development, to advance the digital, networked, and open literacies of teachers and administrators. Inclusion requires technology as a pillar, which means all teachers must foster ways to support learner voice, choice, and access through technology. Furthermore, a deeper understanding is needed to develop a critical lens of digital pedagogy, so as not to fall deep into the pervasive “tech ninja” or “corporate-certified educator” approach. For too long, the K–12 sector has been the target of corporate integration and has perpetuated exclusion. To address this, the Open/Technology in Education, Society, and Scholarship Association (OTESSA), a new Canada-based academic and professional association, was formed to drive research, innovation in practice, and advocacy. In its 2021 federal pre-budget submission, it recently advocated for better supports for both K–12 and post-secondary in the areas of digital, online, and open education.

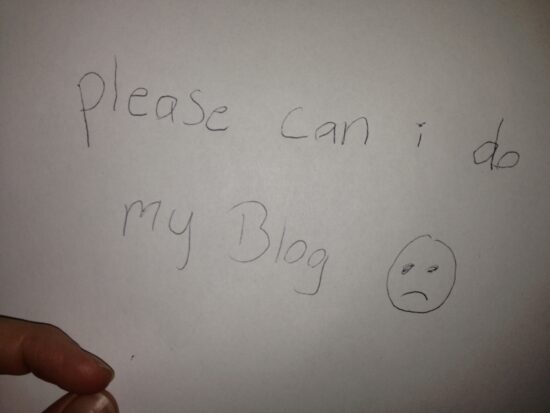

Technology presents rich options for inclusion, but discernment is required, for example, in order to mitigate corporate interests in education (Gilliard, 2018); navigate issues around learner privacy, consent, and data ownership; develop and implement rich online learning strategies and technologies; and identify protections needed to address inequities experienced by marginalized learners (e.g. digital redlining). Not everyone experiences the internet in the same way. Some learners may depend on it for expression of learner voice, when speaking in the physical classroom is not possible (see Figure 2). Some require advocacy to access technology, while others need protection from online harassment. It is no longer appropriate for a teacher to decide not to learn how to incorporate technology, nor is it appropriate for districts or governments not to implement supports for teachers.

Figure 2: Elementary Learner Note Asking for Blogging as a Means of Expression

Photo: Valerie Irvine (with permission), CC BY 4.0.

Learning about technology can be a stressful experience. However, practica are similarly stressful experiences for pre-service teachers, with experiences of failure throughout – yet these challenges during face-to-face teaching do not deter most early career educators from continuing. In fact, failure is expected, and these teachers are encouraged to find supports as they learn and iterate in their practice. With forays into technology integration and exploring online modes, teachers and administrators need to work through challenges to discover practices that work best in their context and for their learners. What we do know is that face-to-face classes cannot simply be transferred online; they need to be adapted. As educators, we need to continue experiencing and learning from failures, reflecting and iterating, regardless of modality, and with proper supports.

In my 2019 offering of a multi-access course with a cohort of 25 MEd learners, I received 5/5 teaching evaluations – but I have been iterating my approaches since 2007. I was fortunate to teach my Educational Technology MEd cohort again in July 2020, after the learners had been through an incredibly stressful spring with the pivot. Many were eager to reflect on their pivot teaching experiences and determine how to return to school in the fall with new designs and solutions. After having this chance to reflect and read relevant research, the cohort co-created a website that shared remote teaching resources that they developed to assist others (Remote Teaching Resources, n.d.). Teachers are the key to shifts in our education system, but they cannot do it alone.

While it varies by school district and province, modality bias continues in that many online schools are seen as a cash cow for a district. In many collective agreements, there is weak language around the protection of online teachers compared to bricks-and-mortar ones, and this in turn weakens supports for learners. Many of the online schools I have visited use asynchronous learning only, continuous enrolment, and large class sizes, compared to local in-person schools. If we truly want an equitable school system, we need to start by providing online learners the same class sizes and the same access to dynamic pedagogical approaches. If we want to break the bias against online schooling as passive, then we need to stop perpetuating the mechanisms that make it a self-fulfilling prophecy. It is my strong belief that our K–12 school system needs to move toward embedding online learning within local catchment schools to support inclusion and flexibility, and to ensure equal standards are provided to online learners in terms of class sizes and supports. This may also ensure that when learners experience times when they need flexibility, they can be supported without leaving the public system. All too often, once they leave, they are unlikely to return. As a result of full inclusion, more teacher positions will be retained to be there for the learners.

THE INTERSECTION between technology and education is complex and requires an informed and nuanced approach. We cannot return to pre-pandemic teaching, because all of our stakeholders have been changed by the pandemic. It’s time to check our individual and systemic biases and take steps to correct the inequities – and never go back.

Photo credit: Adobe Stock

This is part of the first edition of Education Canada, powered by voicEd radio, a cross-platform professional learning experience.

EXPLORE THE LATEST EDITION OF EDUCATION CANADA, POWERED BY VOICED RADIO (MARCH 2022)

Have you listened to the lively podcast episode featuring Dr. Valerie Irvine, among other researchers? Listen here!

References

BCcampus. (2020, October 31). $20 million in 2020. https://bccampus.ca/2020/10/31/20-million-in-2020

BCEdAccess. (2020, August 18). Survey results show need for clarity and flexibility in #BCED fall plans. https://bcedaccess.com/2020/08/18/survey-results-2

BCEdAccess. (2021). Considering leaving the system. https://bcedaccess.com/2021/07/02/report

Clark, R. E., & Feldon, D. F. (2014). Ten common but questionable principles of multimedia. In R. E. Mayer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139547369

Gilliard, C. (2018). How ed tech is exploiting students. Chronicle of Higher Education, 64(31), 1–1.

Irvine, V. (2020a). The landscape of merging modalities. EDUCAUSE Review, 55(4). https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/10/the-landscape-of-merging-modalities

Irvine et al. (2013). Realigning higher education for the 21st-century learner through multi-access learning. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 9(2). https://jolt.merlot.org/vol9no2/irvine_0613.htm

Mayer, R. E. (Ed.) (2014). The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139547369

Miller, E. (2019, September 17). Clark vs. Kozma – media and learning. MISSMILLERSLEARNNGJOURNEY. https://missmillerslearningjourney.opened.ca/2019/09/17/clark-vs-kozma-media-and-learning

National Research Center for Distance Education and Technological Advancements. (2019). No significant difference. https://detaresearch.org/research-support/no-significant-difference

OTESSA. (2021, August 9). Sharing our OTESSA federal pre-budget submission. https://otessa.org/news/sharing-our-otessa-federal-pre-budget-submission

Remote Teaching Resources. (n.d.). About. https://edtechuvic.ca/remoteteaching

School District 69 Qualicum. (n.d.). Restart Plan. https://web.archive.org/web/20200924133657/https://www.sd69.bc.ca/Lists/Announcements/Attachments/385/SD69%20Restart%20Plan%20with%20UPDATED%20COVID-19%20Health%20and%20Safety%20Guidelines%20-%20September%203%202020.pdf

Wiley, D. (2017, May 2). OER-enabled pedagogy. Improved Learning. https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/5009