Inclusive Education Supported through Multiliteracies Pedagogy

Teachers provide insight on fostering lifelong learning and cultural diversity in their classrooms

THIS ARTICLE DRAWS on four high school teachers’ experiences to show how a multiliteracies approach can be practised in the classroom. Multiliteracies envisions inclusive education that encompasses:

- cultural and linguistic plurality

- a strong commitment to social justice issues

- technology that enhances pedagogy

- incorporating multimodalities into teaching that draw upon a variety of modes including visual, linguistic, gestural, oral, and spatial.

The examples we discuss are drawn from a national research study, funded by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Insight Grant. Our research explores multiliteracies in Grades 7–12 classrooms and adult community spaces.

Lifelong learning and global citizenship

Lifelong learning is not just about acquiring workplace skills. It offers a vision for a more just, compassionate, and creative society based on the values of “participatory democracy” (Brookfield & Holst, 2011, p. 5). Ideally, adolescents’ education prepares them to become adults who will engage with passion, intelligence, and integrity in shaping the world. Teachers foster a disposition for lifelong learning in their students by opening up opportunities for students to think deeply and holistically about meaningful contributions they can make to their societies. Many of the students in our research indicated they felt more engaged in courses when teachers allowed them to follow their own interests and included topics or assignments that explored cultural diversity.

In our study, a Visual Arts teacher provided an interdisciplinary opportunity for her students to collaborate in a multimedia exhibit with the English department’s Indigenous literature course. The teacher noted, “Even through interviews they [students] had conducted with First Nations elders, they wanted to distill it symbolically within a work, and that process alone, coming from an abstraction, and realizing it visually, is a very difficult thing to do.” Shifting from the oral mode to the visual mode, students needed to find ways to visually symbolize their interpretations of the interviews they had conducted with the elders. The teacher observed that students opened up more about their own cultural backgrounds when asked to be a part of this art exhibit. The students’ artwork was shared with a broader audience of teachers, administrators, parents, guardians, and community members. Thus, this exhibit bridged students’ school and home lives.

The New London Group coined the term “multiliteracies” and called for civic pluralism, involving the “formation of new civic spaces and new notions of citizenship” (New London Group, 2000, p. 15). Our research revealed examples of teachers bringing civic pluralism into their pedagogy. The Civics teacher reflected,

“I think it is my job as a teacher to prepare them [students] for life as citizens of the community that they are in, and I try to make sure that whatever I do, whether it be computers or careers or communications technology, it shows them how best to participate in society.”

This teacher involved students in the community’s Youth and Philanthropy Initiative. Students chose a social justice issue, found a local charity that addressed that social issue, and interviewed someone at the charity. The students then created a presentation to convince the Initiative that this charity deserved their $5,000 grant. Through this assignment, the students had to consider, in philosophical and practical terms, what citizenship meant to them. Initially, the teacher encountered some resistance from students about having to go into the community for this assignment, but ultimately they became enthusiastic, and some students even continued working with the charities afterwards.

Inclusive education and equity

Teachers in this study modelled inclusive education by reaching out to their students with significant learning disabilities, using multimodalities and differentiated assessment and evaluation tools. As one Special Education teacher reflected,

“What’s necessary for some, is good for everyone. And so, ensuring that you are helping every student at the ‘just right’ step of their process of learning, enables them to have the confidence and the tools to show you what they know. And just writing it down on a piece of paper is not the best vehicle for every student.”

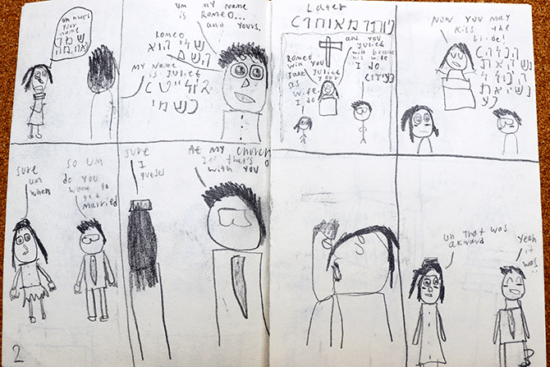

As this teacher recalled, she often had students create “a three-dimensional landscape of where the story takes place. And so, they would tell me why the character starts here doing this… they’re either giving me the plot or they’re focusing on character.” Another example of an alternative assessment involved creating graphic novels that highlighted an important scene or summarized the plot of a literary story through visual means. For example, one student created a graphic novel in English but also translated it into Hebrew. (See photo.) Alternative assessments like these give high-school students the opportunity to demonstrate their knowledge without solely relying on the written mode to express themselves.

In another secondary classroom for students with special needs, a Biology teacher similarly engaged in a multimodal teaching strategy. She explained how she worked with her students to build a model of lungs using balloons. She wanted students to physically see how the diaphragm’s contraction makes the lungs expand. The teacher commented that building the model helped the students “concretely grasp” this abstract concept.

This teacher’s assessment used multimodalities: tactile (blowing on balloons), spatial (making organs proportionate), visual (getting colours and shapes accurate), gestural (ensuring movement mimics human respiration), and oral (team discussions). To follow up, she consolidated students’ knowledge by having them create an interactive book about the respiratory system. (See photo.) Theorists such as Kalantzis et al. (2016) believe that “knowing how to represent and communicate things in multiple modes is a way to get a multifaceted and, in this sense, a deeper understanding” (p. 234). Teachers in this research promoted student success and a deeper understanding by building multimodalities into their assessment practices.

Cultural diversity as an asset in any classroom

An Art teacher in the study questioned, “What would life be like without people wondering and making and doing and creating meaning and connecting culture and using our humanity to inform the good work of the future?” She believed in the importance of identity exploration through various artistic forms. One of her students explored religious identity. This teacher recalled that the student created “a portrait of a girl wearing a hijab – or as an Arabic [sic] student would say a ‘hijabi girl’ – and there were colours all over the hijab that revealed she was wearing [it] as a crown.” Later, that same student painted a portrait of Martin Luther King Jr. Her teacher commented on the power of students creating portraits to represent diversity in a positive light. Serafini (2014) makes the point that “visual literacy combines psychological theories of perception with sociocultural and critical aspects of visual design” (p. 29). Through visual literacy, these young student-artists negotiated ways to visually communicate their interpretations of cultural diversity. In an interview, another student said, “I think it’s important to maintain what was brought down from different cultures. And that way we get to see different views on teaching and different styles.”

Recognizing the importance of cultural and linguistic diversity on students’ experience, a Civics teacher discussed an assignment she used that encouraged students in a rural, monocultural school to think analytically about their community. She explained,

“What I have the students do is create a cultural brochure that introduces immigrant workers to differences that they might face working in Canada as opposed to in their home country. So, it forces the students to actually examine what culture is like here.”

This assignment allowed students to reflect critically on their own culture, which they were so fully immersed in that it might have felt invisible to them. This teacher, as a person of colour herself, recognized that it is vital when teaching a homogenous student body to engage in critical thinking about cultural diversity to encourage students to be prepared for their futures in an increasingly globalized, heterogeneous society.

THE MULTILITERACIES PROJECT web platform (www.multiliteraciesproject.com), founded on this research, is designed for classroom teachers and adult educators to provide them with free resources and ideas for teaching using a multiliteracies approach. The theory of multiliteracies offers a practical way forward for teachers to foster an inclusive classroom that allows students of diverse backgrounds and levels of abilities to thrive in their school classrooms and beyond.

All Photos: courtesy of authors

References

Brookfield, S. D., & Holst, J. D. (2011). Radicalizing learning: Adult education for a just world. Jossey-Bass.

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (Eds.). (2000). Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures. Psychology Press.

Kalantzis, M., Cope, B., Chan, E. et al. (2016). Literacies. Cambridge University Press.

New London Group. (2000). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. In B. Cope & M. Kalantzis (Eds.), Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures (pp. 9–38). Routledge.

Serafini, F. (2014). Reading the visual: An introduction to teaching multimodal literacy. Teachers College Press.