Nunavik’s Compassionate Schools

Leading the way in district-wide trauma-informed approaches

Nunavik’s Kativik Ilisarniliriniq school board launched the Compassionate Schools initiative to better support its students, who experience disparities in health and well-being. Elements of the program include training in understanding trauma, Restorative Practice, and a universal system of Positive Behaviour Interventions and Support (PBIS).

Kativik Ilisarniliriniq is a school board located in Nunavik, a remote region in northern Quebec. Inuit, who have inhabited the region for thousands of years, live in 14 small fly-in villages spaced along the Hudson and Ungava coasts.

The project aims at facilitating the social, emotional and academic success of students, while simultaneously educating teachers and staff on the impacts of trauma on the brain; it also seeks to provide maximum support to teachers.

The region’s legacy of colonization includes residential schools, forced relocations to the high Arctic, sled dog slaughters and the Sixties Scoop,1 yet it suffers from an extreme paucity of resources to help people heal from the impacts of intergenerational trauma. As a result, the current generation of children experiences disparities in health and well-being.

Members of the region’s school board, Kativik Ilisarniliriniq (KI), wanted to find a solution to the resulting challenges they saw students facing. Inspired by schools in Washington that had dealt with similar challenges, KI launched Compassionate Schools as a pilot project in three of its 17 schools in 2012.

The project aims at facilitating the social, emotional and academic success of students, while simultaneously educating teachers and staff on the impacts of trauma on the brain; it also seeks to provide maximum support to teachers. Each school adapts the approach to its home community so as to establish a positive, safe, consistent and predictable framework that is culturally relevant. Schools receive training as well as individual support from a dedicated coach on staff. A travelling regional pedagogical counsellor also visits regularly to encourage reflective practices and build skills in improving class climate, student engagement, and support for students with challenging behaviours.

The progressive implementation of the Compassionate Schools framework reached an important milestone in 2017. That year, all 17 schools had received training on teaching practices that take into account the trauma that may affect some students, and were introduced to the design of a universal system of Positive Behaviour Interventions and Support (PBIS), which creates a consistent intervention approach throughout the entire school. All schools additionally received training in Restorative Practices, an approach that helps facilitate relationships and trust. Schools use these as a foundation for responding to wrongdoing in a way that promotes community outreach, empathy and accountability.

The foundation of PBIS is universal prevention for all students and staff. Examples include teaching behavioural expectations school-wide as well as adopting school-wide approaches to recognizing positive behaviours. Teachers play a major role at this tier as they build relationships with students that can break down the self-doubt, hopelessness, fear, and barriers against trust that can plague students who have experienced trauma. By having clear, consistently taught expectations with frequent feedback, teaching students self-regulation skills, providing calm areas, and striving to identify and meet the needs behind students’ behaviours, teachers and other staff are able to create environments that are psychologically safe for students; as a result, they can feel confident to take the risks necessary to grow and succeed.

Early interventions are introduced for at-risk students who do not respond to the universal prevention. “Check-in Check-out” is one such intervention that involves pairing students with a trusted mentor who provides daily encouragement and support. Goals are set using a progress report with specific co-constructed objectives for which the student receives feedback throughout the day from each teacher. To date, school teams from 15 of our schools have received training on team processes and interventions for at-risk students.

While previously Compassionate Schools Services was a stand-alone project, it has recently merged with Complementary Services. This department is responsible for special education, student counseling and psychological services, as well as a wide variety of other support services. The new department, Complementary and Compassionate Services, led by Tunu Napartuk, will be well positioned to ensure a continuum of academic, mental health and special education services at all levels of prevention and intervention, using a common framework.

With the integration of the Compassionate Schools approach into the delivery of special education and psychological services to students, we are proud to see the school board at the forefront of some of the best practices identified by recent Canadian and international research.

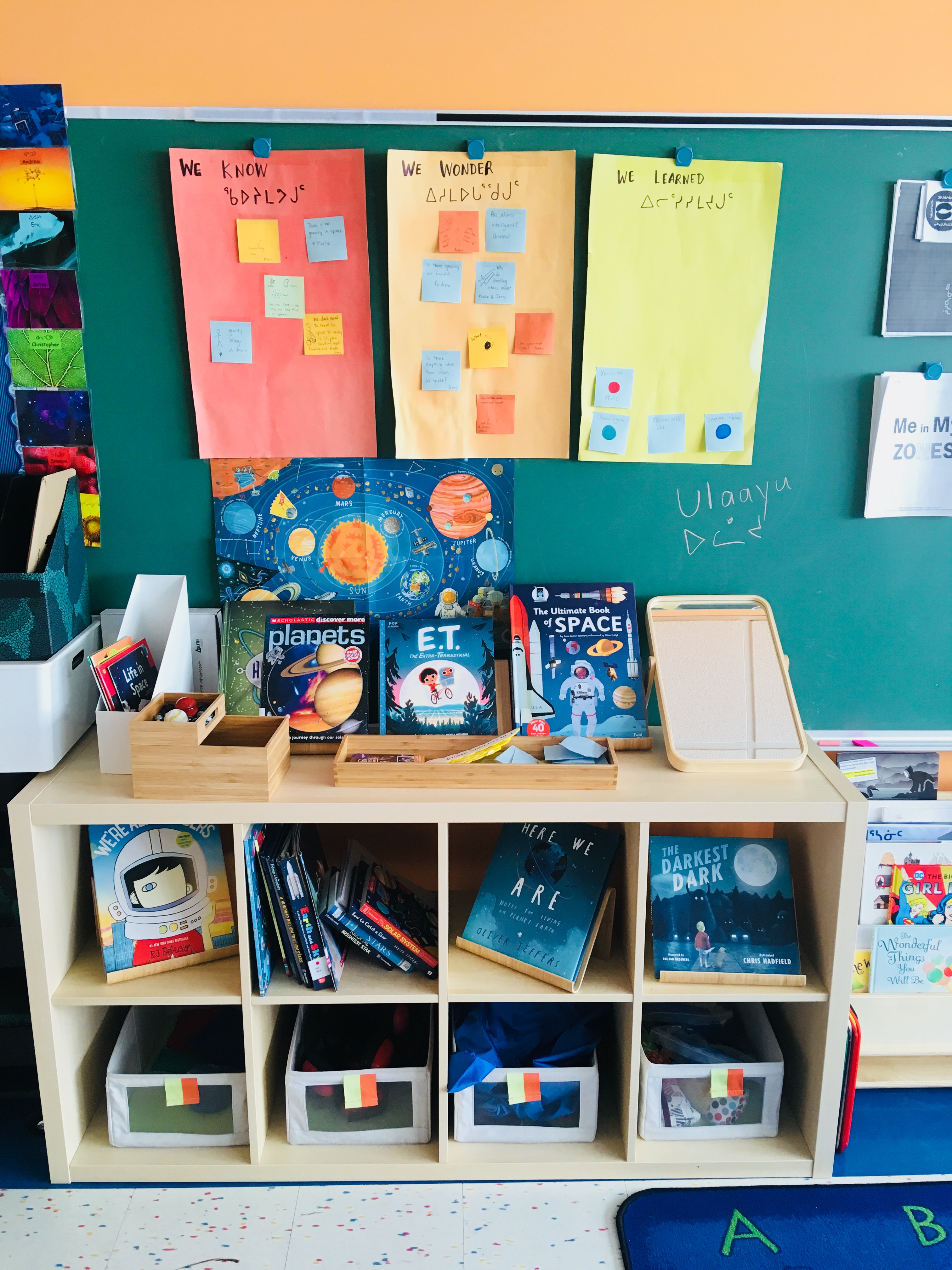

Inside the Harmony Room

By Jenny McManus

The beat of the drum brings the group together around the carpet. We celebrate the morning improvising an ayaya song to notice the subtle changes in nature – like the sun shining brighter through our window – to recognize students’ effort and achievement, and to strengthen their memory recall. Beaming with pride, the students clap out the number of stars they earned that morning as tokens for following expectations based on our school values of respect (susutsaniq), unity (tatiqatigiiniq), harmony (saimautiniq), and vision (tukimuatsianiq).

Every morning, we remind ourselves to listen openly, stick together, be peaceful, and dream big with posters on the wall that we made together, hand gestures that silently redirect, and smaller cards to flip to indicate unexpected behaviour. Each student has a colour on the wall for displaying their names, stars and evidence of learning. In the Saimautivik, or Harmony Room, they find a sense of belonging that nurtures friendships, empathy, and growth.

The Saimautivik is a social and emotional learning space at Pitakallak School in Kuujjuaq. Spearheaded by Jenny McManus, the Compassionate School teacher, it provides a home base for a nurture group, social skills groups, and extracurricular activities. Nurture groups are inclusive interventions for students that the Boxall profile (an online assessment tool) identifies as having delays in social, emotional, or behavioural development and who are struggling to flourish in the regular classroom environment. The Saimautivik brings together teachers and support staff to provide evidence-based practices to support our students in need and experiment with new directions in learning.

As a traditional Inuit value, harmony brings peace between people, agreement between ideas, and understanding in place of conflict. A classroom can be warm and inviting, with comfortable spaces for gathering and calming down, tables for sharing meals or collaborative projects, and nooks for using hands-on materials. The Saimautivik’s bright colours invite play and creativity, yet its organization supports the daily routines and serious, focused study.

Using tools that Compassionate Schools and Complementary Services promote the targeted interventions are supporting growth and change on a school-wide level.

Through the security of routine and predictability, caring adults who model positive relationships, clearly and mutually defined expectations, food sharing, opportunities for hands-on and paper-based numeracy and literacy, and engaging activities that are developmentally appropriate, the students make great gains in their development in a short period of time. Using tools that Compassionate Schools and Complementary Services promote, such as the Zones of Regulation and other trauma-informed approaches, the targeted interventions are supporting growth and change on a school-wide level.

Teachers, families, and the students themselves share stories of increased confidence, wider social circles, and greater academic achievement. Since the introduction of the intervention halfway through this school year, behavioural referrals have been reduced by half.

Rejected furniture and random supplies used to accumulate in this unused classroom; students would hide there when escaping their responsibilities. Now a place for healing and learning, it challenges the traditional concept of a classroom and the role of a teacher.

Find out more

Join our team! Visit www.kativik.qc.ca to view current job openings!

photo: Jenny McManus

First published in Education Canada, December 2019

Notes

1 The “Sixties Scoop” refers to the large-scale removal or “scooping” of Indigenous children from their homes, communities and families of birth. This practice took place during the late 1950s until the early 1980s and it has affected Inuit communities. The physical and emotional separation from their birth families also left many adoptees with a sense of lost cultural identity, which continues to affect adults and Indigenous communities to this day.