Leading High-Performing School Districts

Nine characteristics of effective districts and the leadership practices that achieve them

School districts are largely invisible and of little interest to the public, except when conflicts among trustees, or between trustees and community groups, generate media attention. School closings, student busing policies and teacher professional development days are examples of issues that predictably attract such attention. While some of these high-profile issues do affect students, the primary work of district leaders to improve the learning and well-being of students is a mystery to most members of the community. The public tends to attribute what students learn exclusively to the very visible schools, teachers and principals with whom they have direct contact. Districts are just not on the public radar – and that makes them politically vulnerable organizations.

Despite their lack of public visibility and political vulnerability, high-performing districts make important contributions to the achievement and well-being of students. Evidence related to this claim, while modest in amount, is longstanding.1

What is it that distinguishes high-performing districts from the rest, and how can these distinguishing features be developed? This is the key question for leaders aiming to enhance the performance of their districts. But evidence to help answer this question is sparse, almost exclusively qualitative in nature and based on relatively weak “outlier” research designs (in which researchers locate a high-performing district and try to figure out why). This is especially troubling when, as some analysts argue,2 school districts ought to be assuming much more leadership for determining the future directions for their schools.

Some analysts argue that school districts ought to be assuming much more leadership for determining the future directions for their schools.

Over the past nine years, a series of initiatives has been undertaken in Ontario by district leaders represented by the Council of Ontario Directors of Education (CODE), in collaboration with the Ministry of Education and its Institute for Educational Leadership (IEL). These initiatives have aimed to identify the characteristics of high-performing districts, the leadership they require and how such leadership can best be developed.

The study of high-performing district characteristics

The first of these initiatives was a series of regional seminars, created with directors, that continued over a period of about three years. Prompted by deliberations during these seminars, the province then funded a large-scale study to identify and describe those characteristics of school systems and their leadership that contribute to significant growth in student achievement and well-being. The study was designed to accomplish this goal by collecting a robust body of quantitative evidence, supplemented with three detailed case studies, about high-performing districts in Ontario.

The framework guiding this study was developed from syntheses of evidence about school system conditions contributing to improved student learning,3 modified through a series of focus groups with directors of education to reflect the policy context and wider environments in which Ontario school systems found themselves. The quantitative portion of the study included survey data collected from 235 district leaders and 1,543 principals in 49 of the 72 districts in the province, along with average, district-level changes in Grades 3, 6, 9 and 10 student math and language achievement over a five-year period. Effects on student achievement4 were significant, and small to moderate in size, for these characteristics:

- broadly shared mission, vision and goals

- a coherent instructional guidance system

- job-embedded professional development provided for all members

- use of evidence to inform decision making

- learning-oriented improvement processes

- a comprehensive approach to leadership development

- a policy-oriented board of trustees

- alignment of policies and procedures with district mission, vision and goals

- productive relationships (internal system and school, parents, community groups, ministry)

In addition, estimating the effects of these district characteristics on students, the study team calculated the effects of both “Professional Leadership” (directors and superintendents) and “Elected Leadership” (trustees) on the other district characteristics. Results indicated that both sources of district leadership had moderate to strong effects on most district characteristics. Professional Leadership had consistently larger effects than Elected Leadership on all but two district characteristics.

The main product of this study, “The Characteristics of High Performing School Districts,”5 was included as the district portion of the Ontario Leadership Framework,6 intended as a guide for school district improvement.

The “Strong Districts” Initiative

While the nine district characteristics are what needs to be developed by senior leaders, how to develop those characteristics was captured in Strong Districts and Their Leadership,7 a paper commissioned by CODE. Using evidence from many sources, this paper provides a more detailed account of the nine characteristics of high-performing districts and also synthesizes existing evidence about the practices and personal leadership resources of “strong” (high-performing) district leaders.

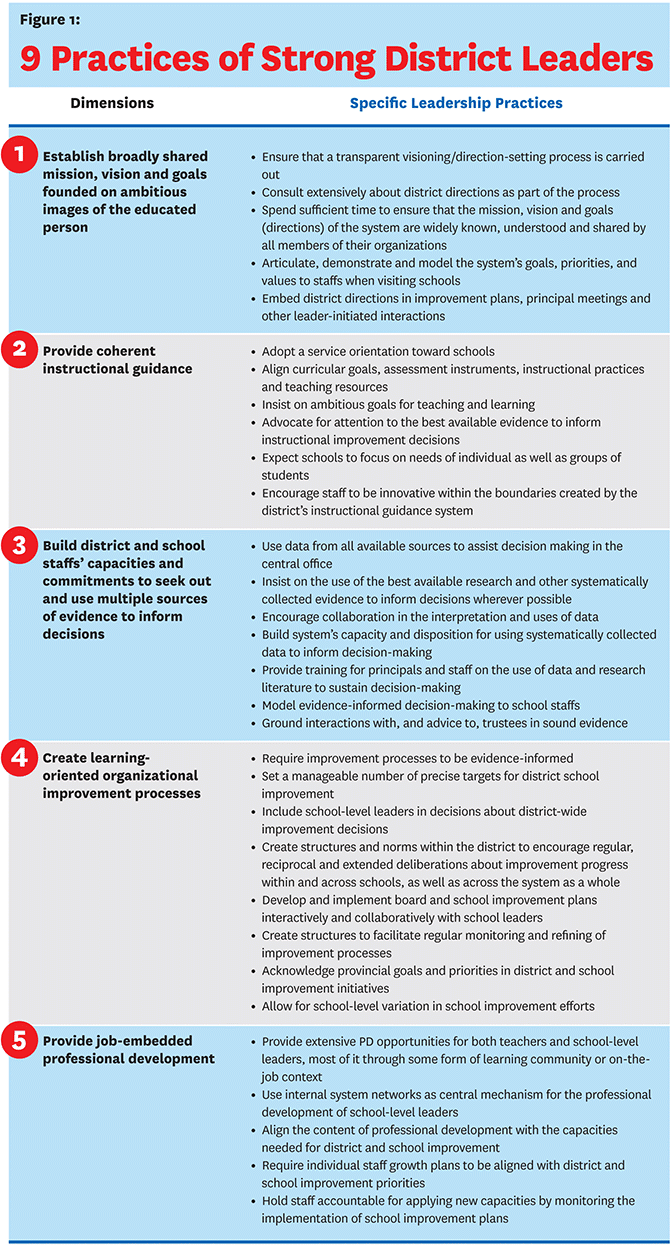

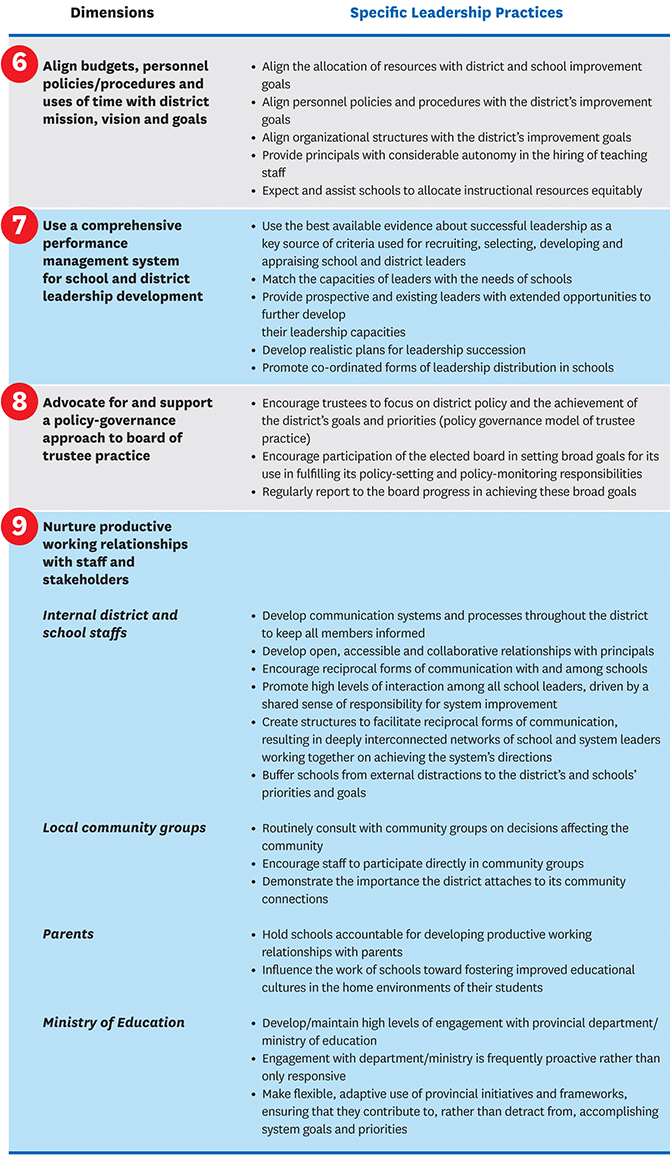

A key finding is that each district characteristic develops in response to a handful of specific leadership practices. While the total number of practices identified is relatively large, it reflects both the extent and complexity of the work done by strong district leaders (see Figure 1).

Underlying almost all strong senior leadership practices are a small number of personal leadership resources. While most are described in the Ontario Leadership Framework, Strong Districts and Their Leadership added two more practices especially relevant for senior district leaders: proactivity and systems thinking. The full paper describes these personal resources and explains why they are part of strong district leadership.

Developing district leadership capacities

After the publication of Strong Districts and Their Leadership, considerable effort was made to introduce its contents to system leaders across the province. Some of the province’s senior district leaders had already begun to use the strong districts framework as a guide for assessing their own districts’ progress and planning for future improvements. But in order to expand use of the research to a substantial majority of districts, a more programmatic opportunity was needed. So CODE, IEL and the Ministry of Education endorsed a proposal to create and field test stand-alone professional development modules aligned with each of the nine characteristics of strong districts. Completed in the spring of 2015,8 each of these modules includes an agenda, a set of slides summarizing relevant research and either two or three case studies. A total of 23 cases were prepared, many of them including video interviews with senior leaders about their cases.

Next steps

A new study, slated to begin in January 2016, is aimed at deepening our understanding of how district leaders can be as strategic as possible in their district improvement efforts. These efforts as a whole illustrate what can be accomplished in the interests of students when policymakers, senior leaders, and researchers engage in authentic and respectful collaboration aimed at a common goal.

En bref: Des dirigeants de conseils scolaires représentés par le Council of Ontario Directors of Education (CODE), en collaboration avec le ministère de l’Éducation et l’Institut de leadership en éducation (ILE) de l’Ontario, ont entrepris une série d’initiatives s’appuyant les unes sur les autres pendant les neuf dernières années. Ces initiatives visaient à dégager les caractéristiques de conseils scolaires performants, le leadership qu’ils requièrent et les façons dont ce leadership peut être développé. Les résultats comprennent l’identification et la description de neuf caractéristiques expliquant les contributions productives des conseils à la croissance des élèves, les approches de leadership favorisant le développement de chacune des neuf caractéristiques, ainsi qu’un programme de huit modules destiné à contribuer à développer ces pratiques chez les dirigeants scolaires. Cet article résume ces travaux et soutient que, dans l’ensemble, ils illustrent ce qui peut être accompli dans l’intérêt des élèves lorsque les responsables de politiques, les cadres supérieurs et les chercheurs collaborent authentiquement et respectueusement en vue d’atteindre un objectif commun.

First published in Education Canada, March 2016

1 For example, P. Coleman and L. LaRoque, “Reaching Out: Instructional leadership in school districts,” Peabody Journal of Education 65, no. 4 (1990): 60-89; K. Leithwood and K. Louis,Linking Leaership to Student Learning (San Francisco: Jossey, 2012); M. Chingos, G. Whitehurst, and M. Gallaher, School District and Student Achievement (Boston: The Brookings Institution, 2013).

2 For example, Coleman and LaRoque, “Reaching Out”; Leithwood and Louis, Linking Leadership to Student Learning; Chingos et al., School District and Student Achievement.

3 For example, Coleman and LaRoque, “Reaching Out”; Leithwood and Louis, Linking Leadership to Student Learning; Chingos et al., School District and Student Achievement.

4 An Effect Size statistic was used to report these results. Even variables with weak effect sizes may be practically consequential depending on costs; multiple variables with weak effect sizes can add up to strong effects. These results are the direct effects of districts on students even though the effects of district characteristics are mediated by many other school and classroom conditions not measured in the study.

5 K. Leithwood and V. N. Azah, “The Characteristics of High Performing School Districts,” Leadership and Policy in Schools (in press).

6 K. Leithwood, The Ontario Leadership Framework 2012 with a Discussion of its Research Foundations (Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Education and the Institute for Educational Leadership, 2012).

7 K. Leithwood, Strong Districts and Their Leadership (Toronto: Paper commissioned by the Council of Ontario Directors of Education, 2013). www.ontariodirectors.ca/projects-current.html

8 K. Leithwood and C. McCullough, Professional Development Modules in Support of Strong Districts and their Leadership (Toronto: Final report to the Institute for Educational Leadership, 2015).