What is a Teacher’s Expertise?

What exactly do teachers do that justifies the claim to be a professional? What is the body of unique expertise that defines a teacher? If you ask that question of most teachers—or parents or students—you are liable to get a rambling response that makes reference to training or experience, and perhaps to some specific disciplinary expertise or personal charisma, but never really answers the question.

What exactly do teachers do that justifies the claim to be a professional? What is the body of unique expertise that defines a teacher? If you ask that question of most teachers—or parents or students—you are liable to get a rambling response that makes reference to training or experience, and perhaps to some specific disciplinary expertise or personal charisma, but never really answers the question.

This is unfortunate because in the absence of such a conceptual framework it is easy to lose sight of the full landscape of issues that constitute teaching professionalism and thus to become narrowly focussed on particular aspects. Having a “big picture” view aids in reflection on experience, self-assessment and professional growth plans, and in dialogue with others about teaching. It also helps the teacher to think strategically about what influences student response and what actions may help or hinder in the quest for student engagement. Moreover, having a shared conceptual framework with others enables richer professional dialogue.

In my previous post I suggested that engagement results from a student’s perception of Connection, Self-Efficacy and Agency—the operative word being perception. Engagement is a voluntary, internally-motivated student response over which a teacher has no direct control. Nonetheless, it is the teacher’s responsibility to do whatever it takes to provoke those perceptions because that is the only route to intellectual engagement and thus to deep learning and transformational outcomes.

Student diversity precludes there being any prescriptive process for achieving this elusive goal, but I believe that one can understand the professional skill set that must be brought to bear, and thus define a teacher’s professional expertise in broad terms, in order to enable clearer thinking and richer discourse about teaching.

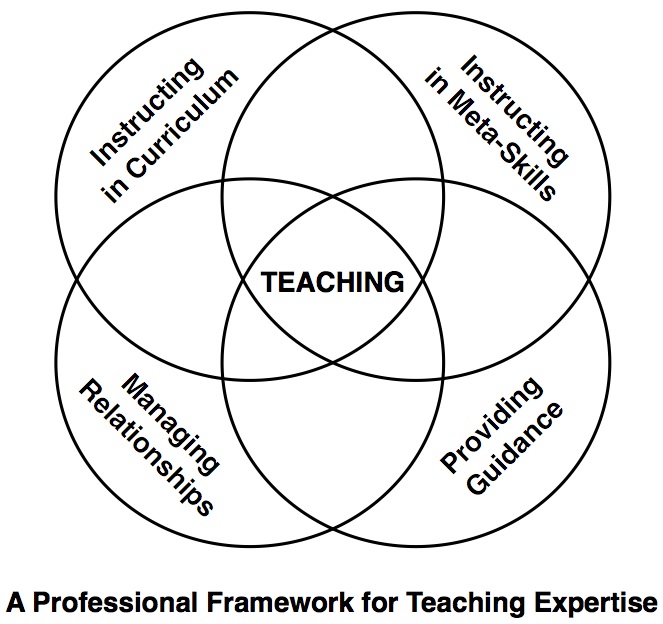

Towards this end of improved strategizing for engagement and more productive professional dialogue in general, I suggest that teaching expertise can be thought of in terms of four cornerstone competencies: managing relationships, instructing in curriculum, instructing in meta-skills and providing guidance. (See footnote).

Each of the four domains is internally complex, they overlap and they are in many ways interdependent, but taken together I believe they provide a useful conceptual framework for the gestalt of a teacher’s professional expertise.

Managing Relationships includes the ability to establish appropriate relationships with students, particularly those with whom it is hardest to so, and creating a classroom culture in which students have supportive learning-focussed relationships with each other. In addition, a teacher must form constructive relationships with colleagues and parents, and once again it is when these relationships are challenging that a teacher’s expertise in creating and managing relationships is demonstrated.

Instruction in Curriculum includes everything from the strategic level of curriculum and unit planning to the tactical level of classroom techniques such as asking open-ended questions or organizing a student debate. It is the part of the framework that is most often the focus of conversations about teaching and of professional development activities. That is OK, but if we are exclusively focussed on building an instructional repertoire and neglect the other domains in the framework then teaching will not be effective because no matter how polished a teacher’s instructional skills, learners will not thrive unless there is equal proficiency in the other cornerstone competencies.

Instruction in Meta-Skills means helping students to develop enabling abilities such as organizing themselves, setting goals, persisting in the face of difficulty, collaborating with others, disagreeing agreeably, thinking critically, keeping an open mind and so on. While these skills are generally not mentioned explicitly in curriculum documents, they are essential to learning success and one cannot assume that students will develop them on their own. Although they will not show up on report cards, these foundational skills may be greater determinants of a child’s future life prospects than the curriculum itself.

Providing Guidance begins with the fact that a teacher stands in loco parentis and is, therefore, responsible for providing social and emotional support for learners (which is true right through graduate school). There are limits to this, of course, but within the instructional context a teacher must provide personal support and encouragement as well as instructional support. Additionally, this quadrant includes formative and summative assessment, from the feedback that is embedded in ongoing interaction with students through the more formal mechanisms that occur periodically. The heart of the matter for the teacher, however, is providing formative assessment as an embedded and ongoing part of instruction. Peer and self-assessment are also important and a teacher must be able to create the environment for them to flourish as well.

Having such a conceptual framework would, I believe, help a novice teacher to connect the dots of their pre-service training and help them to make more cumulative sense of their subsequent teaching and pro-d experiences. In the absence of such a framework these experiences can too easily seem cacophonous and overwhelming. Throughout a career, such a framework can help a teacher to plan more strategically and to explain more succinctly and coherently to students, parents and colleagues what s/he does and why. In relation to the challenge of engagement, it describes the types of “levers” that a teacher can employ to elicit student perceptions and responses that are liable to result in their internally motivated decision to engage deeply in their learning.

What makes a teacher effective is a complex personal blend of understandings, skills and dispositions. It is as ineffable as parenting—with a rather large family!—and reducing the elements to a list, or even a framework, inevitably fails to capture the subtle elegance of truly good teaching, but I hope that this framework captures enough of the essence to be helpful for personal reflection and professional discourse.

Footnote: There are many existing frameworks. ASCD, for example, promotes Charlotte Danielson’s Framework for Teaching and the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership has produced Professional Standards for Teachers. I find these and other examples to often be too complex and/or focussed on teacher evaluation to be used as a scaffold for teachers’ own reflection on experience and planning for professional growth, but I do not suggest that the version described here is the Holy Grail of frameworks. If there is one that suits you better or if you wish to design you own, please do so. What is important is that you have a framework that is simple and explicit to help you think and talk about your practice in a holistic way.

Previous blog – What Leads to Engagement?