Trauma-Informed Practice

Why educator wellbeing matters

On behalf of the Ontario Principals’ Council

Most initiatives in education begin with the introduction of a new word. Think “wellbeing,” “equity,” or “reconciliation.” Each term serves as a beacon illuminating new layers of complexity in education, revealing deeper student needs or system requirements, inspiring more meaningful goals, and pointing the way to better teaching and leadership practices.

And yet, as each word is systemically blended into the daily parlance of education, its unique brightness begins to dim. Its disruptive power and innovative potential fades. Terms that once challenged educators to think with greater pedagogical breadth and depth are used so frequently – and, at times, so casually – that their meaning becomes diminished. Ironically, words meant to capture our attention, create a sense of urgency, and sensitize us to the complexities of human experience, often risk simply becoming yet another education buzzword among many.

Arguably, the word “trauma”1 is one such word. Having entered the fringes of education less than two decades ago, the term – along with its associated “trauma-informed” and “trauma-sensitive” – is now mainstream. Spurred on by the pandemic, the idea that schools are not only places of learning, but should also be places of “healing,” is now a widespread educational aspiration.

But how are we actually doing when it comes to genuinely supporting students who experience trauma? How are educators feeling about their understanding of trauma, and their ability to effectively address the complications that trauma often brings to the classroom? The Ontario Principals’ Council (OPC) recently undertook an online survey and qualitative interview study of school administrators across Ontario to better understand this question. In all, 652 principals and vice principals completed the survey, representing both elementary and secondary schools in 25 English public boards throughout the province. The complete report can be found online at www.principals.ca/RPR.

Student trauma matters, now more than ever

Administrators were first asked to estimate the percentage of students in their schools impacted by trauma, both prior to the pandemic and following it. Almost one-third of administrators estimated that 10 percent or fewer of their student population was impacted by trauma prior to the pandemic. However, estimates grew significantly when school administrators were asked to consider their students within the context of the pandemic. Almost one in four administrators believed that 20–30 percent of their students were impacted by trauma. The number of administrators who believed that 30–50 percent of their students were impacted by trauma doubled when considering the pandemic.

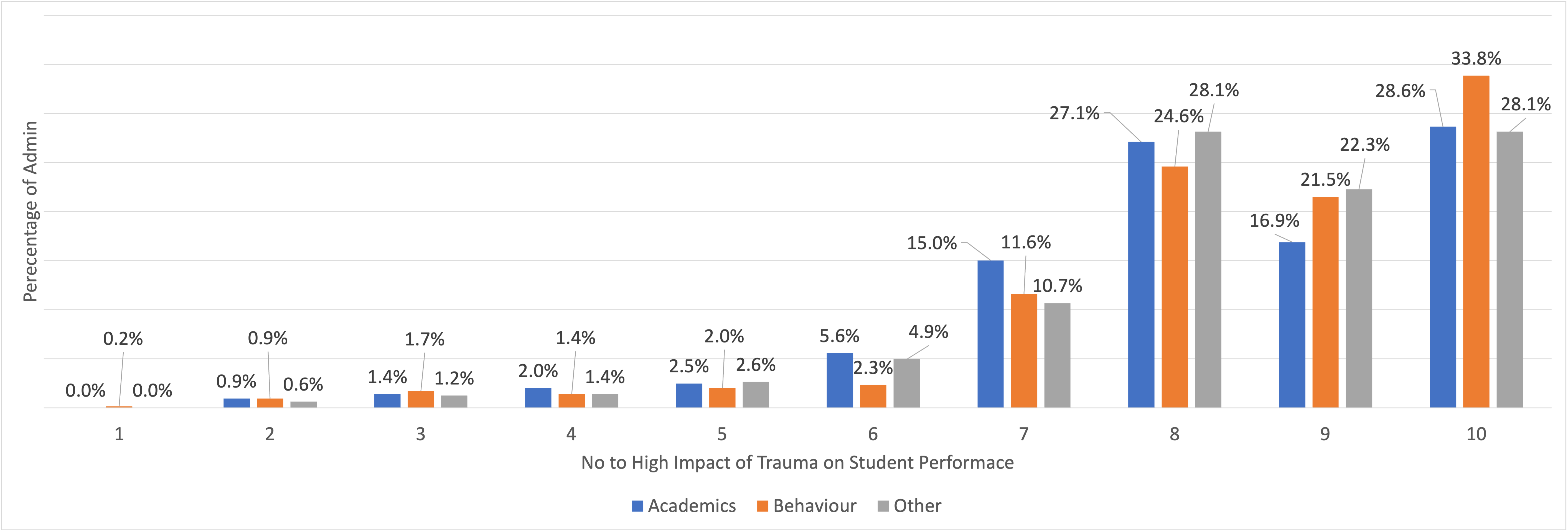

When asked to rate the degree to which they believe trauma is negatively affecting student performance on a scale of 1 (low impact) to 10 (high impact), administrators indicated a strong conviction that trauma is significantly impacting academics, behaviour, and other student issues such as attendance or overall attitude toward school (See Figure 1). For example, more than one-quarter of administrators rated the impact of trauma on academic performance as 10/10. One-third of administrators rated trauma’s impact on behaviour as 10/10. More than one-quarter of administrators rated the impact of trauma on attendance or overall attitude toward school as 10/10.

Figure 1: Overall, what impact do you believe the effects of trauma have on your students’ academic performance, behaviour, and other student issues such as attendance or attitude toward school?

Given the prevalence of trauma, administrators reported that a significant amount of teaching time is spent dealing with issues connected to student trauma. For example, half of the administrators estimated that their staff spend 10–30 percent of their teaching time dealing with issues related to student trauma. One in ten administrators estimated that 40–60 percent of teaching time is spent dealing with student trauma-related concerns.

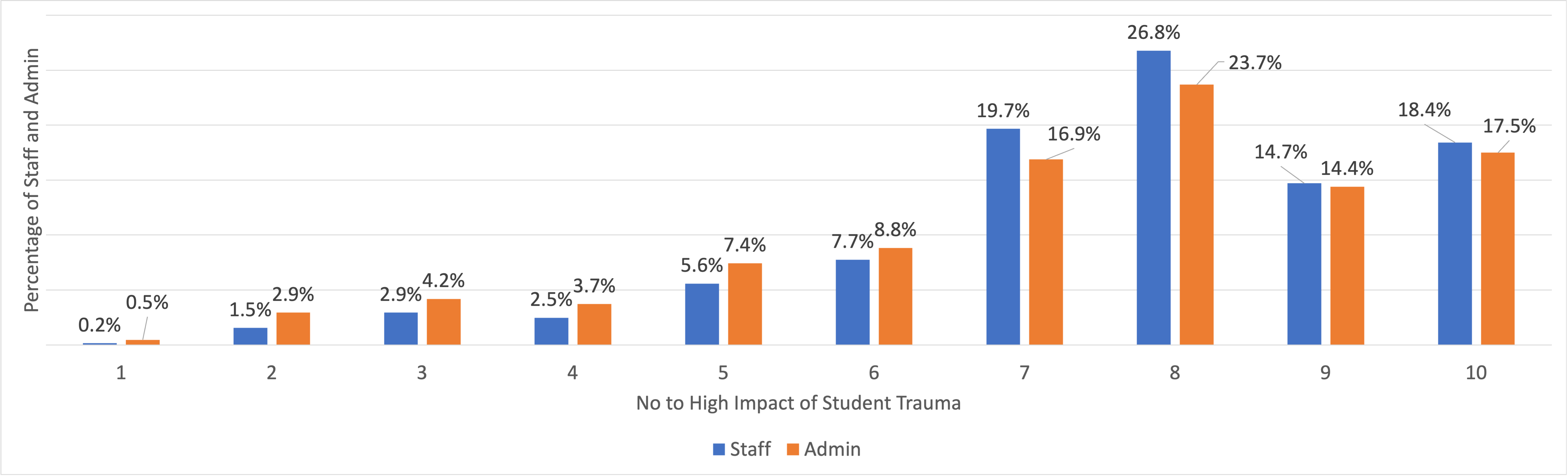

Trauma impacts educators, too

Student trauma also impacts educators. For example, on a scale of 1 (no impact) to 10 (high impact), 80 percent of administrators rated the negative impact of dealing with student trauma on educator wellbeing as 7/10 or higher. One-third of administrators rated the impact as 9/10 or higher. School administrators also reported experiencing the effects of dealing with student trauma on their own wellbeing. Almost three-quarters of administrators rated the impact as 7/10 or higher. Close to 1 in 5 administrators reported the impact as 10/10 (See Figure 2).

Figure 2: To what degree does dealing with student trauma negatively impact your staff’s wellbeing, or your wellbeing?

Necessity of trauma sensitivity

Consistent with their concern about the prevalence of trauma in their students and its impact on school success, administrators were strongly in favour of adopting a trauma-sensitive approach in education, with over half rating the necessity as 10/10. A total of 85 percent of administrators rated the necessity as 8/10 or higher.

However, administrators tended to rate their schools’ present ability to support students affected by trauma as moderate. On a scale of 1 (poor) to 10 (excellent), almost 1 in 10 administrators rated their school as 2 or lower, while less than 2 percent of administrators rated their school as 9/10 or better. Just over half of administrators rated their school’s ability as 5/10 or poorer.

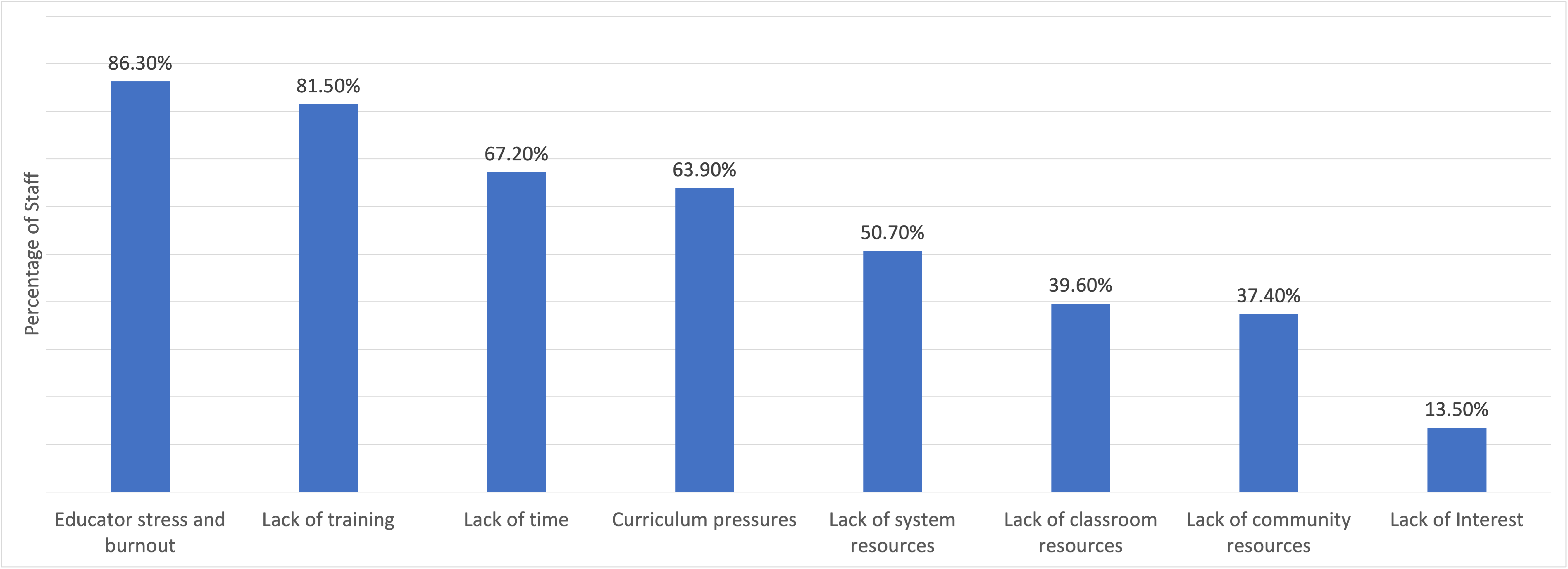

Barriers to trauma-sensitive education

Given their struggles to more effectively support student trauma, administrators were asked to indicate the barriers that their staff face in more fully practising a trauma-sensitive approach. The most prevalent barrier, identified by 86 percent of administrators, was educator stress and burnout. This was closely followed by lack of staff training, lack of staff time, and curriculum pressures (See Figure 3).

Figure 3: What, if anything, gets in the way of your staff’s ability to consistently adopt a trauma-sensitive approach? (Check all that apply)

Administrators also reported facing significant barriers when it came to leading a school-wide trauma-sensitive approach. The most frequently reported barrier, identified by three-quarters of administrators, were the competing demands of other administrative duties. Two-thirds of administrators identified stress and burnout as a barrier. This was closely followed by an overall lack of time. Half of the administrators also identified lack of training as a barrier, followed by lack of system support.

From the interviews with individual administrators, it was clear that they and their staff view student trauma as an important priority in education. However, it was also clear that most educators are struggling to address trauma effectively. They want to do better, but they find themselves exhausted by existing demands and often overwhelmed by the prospect of taking on more, especially something that often feels beyond their level of expertise.

Principals share their experience

| Sometimes when there is so much going on, with trauma, behaviours from students, staff anxiety and stress, it is a lot of stress put on administration. This is starting to burn me out – as well as colleagues that I speak to about this.

I am finding it more and more difficult to approach problems with staff and students with the level of empathy and patience that I feel that I should have. I am feeling very “done”… if that makes sense. The wearing fatigue plays a huge role in mustering the resilience, by the end of the week, to fully and deeply engage in problem-solving. The cumulative effects of trauma are what I am attempting to navigate – and I think many of my colleagues are as well. Quite frankly, there are too many items that are affecting our role as leaders. We are NOT health experts, trauma experts and the board really has no foundations on this either. Nor do they know how to support people on the front lines. Schools are flailing, as is morale. Let us lead without all these other unexpected expectations that affect schools! I’ve become hyper aware of the relationship between trauma (or perceived trauma) and behaviour of students. I am increasingly aware that my expertise in identifying trauma and dealing with behaviour resulting from trauma is insufficient on a daily basis. It has, however, created a strong team bond at our school in order to, every day, try to meet the needs of all students. |

Widening the trauma lens at school

Childhood trauma is first and foremost a fundamental violation of the safety and security of relationships with adults. Therefore, safety and security can only be restored through relationships with adults. And yet, while healing must happen through adults, such healing is rarely easy or straightforward, especially in the classroom.

Supporting students who have suffered trauma is often challenging. The experience of each student is vastly different and the ways in which trauma affects them is wide-ranging and complex. Some students may be oppositional, others overly compliant, while still others are utterly disengaged. Students often require a lot of time and support, progress is slow, and solutions are found through trial and error. Boundaries are tested, core beliefs are challenged, and personal emotional hot buttons are often pushed.

Educators have a critical role to play in helping students heal from the effects of trauma. However, becoming trauma-informed involves more than simply adding “trauma-sensitive” practices to the existing work of educators. While it includes providing educators with practical classroom tools, it also requires a widening of the wellbeing lens toward a greater awareness of the many pressures already on educators. It requires changes on a system level to relieve some of those pressures and the strengthening of organizational structures to more effectively support educator wellbeing. This includes the creation of workplace cultures that genuinely allow educators to be vulnerable and to share both their successes and failures without judgment. It involves moving away from simply reminding educators to practise self-care, to a greater organizational commitment to mutual care. It means ensuring that educators don’t feel alone in the classroom. Above all, it means remembering that of all the teaching strategies, the “strategy” that matters the most is the educator themselves.

LEARN MORE ABOUT HOW EDCAN SUPPORTS K-12 WORKPLACE WELLBEING

note

[1] Trauma is the lasting emotional response that often results from living through a distressing event. Experiencing a traumatic event can harm a person’s sense of safety, sense of self and ability to regulate emotions and navigate relationships. Long after the traumatic event occurs, people with trauma can often feel shame, helplessness, powerlessness and intense fear. (The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health)

Photo: iStock

First published in Education Canada, September 2023