(Trans-multi)culturally Responsive Education

A critical framework for responding to student diversity

A (trans-multi)culturally responsive education calls for beginning with what the students have, including their cultural ways of knowing, the diversity of their learning experiences, and their self-identified cultural identities. It asks teachers to (re)think: What do we need to “undo” and “unlearn” to (re)create curriculum that is responsive to the multiple needs of today’s diverse students?

“It’s students’ cultural diversity that makes it enjoyable to teach. I can’t imagine teaching in a monocultural classroom… cultural diversity is a gift.”

Canadian teachers in general recognize and value student diversity. Then why, in many Canadian classrooms, do culturally diverse students find themselves “lacking” and “lagging behind”? Why is there a dissatisfaction among parents that schools are not effectively tapping into the potential of their children? For example, a teacher in my recently completed doctoral research shared: “The parents of certain cultural backgrounds complain that I am teaching ‘baby math’ and that their children can do a higher math. I tell them that I am teaching a Canadian curriculum in Canadian style!” Another teacher justified her teaching by claiming: “It makes sense that if they [culturally diverse students] have come to Canada, they need to adapt to our Canadian style of teaching.” Yet another teacher, who felt that only a third of students understand what is being taught in their urban Canadian classroom, confessed: “Sometimes, I wish that I had all Canadian children in my classroom.”

Looking at these statements, one may wonder, what do we mean by a “Canadian style” of teaching in a contemporary, diversity-rich classroom of Canada – a country that takes pride in its multicultural national identity? Who are the students in these classrooms? What do we mean when we wish for a classroom with all “Canadian children”? What could be a curriculum of initiation for these “Canadian children” who are increasingly becoming more and more diverse – culturally, ethnically, linguistically, religiously, geographically, and also in terms of gender(ed) sexual identities, exceptionalities or dis/abilities? No teacher enters in a classroom with the intentions of making learning difficult or incomprehensible for their students. So, why do teachers in these Canadian classrooms continue to teach in a prescribed style of teaching that is trapped within the boundaries of official curricula?

The Canadian context

Contemporary Canadian classrooms mirror the growing cultural diversity that is inherent in every aspect of Canadian life. Recent population projections suggest that immigrants, embracing the diversity of more than 200 ethnic origins, will account for 25-30 percent of Canada’s population by the year 2036.1 The Indigenous populations of the country add to this cultural diversity. This exponential increase in the number of students that have come from diverse cultural backgrounds makes multicultural education an essential requirement in contemporary Canadian classrooms.

In the Canadian Teachers’ Federation’s 2012 national teacher survey, the teachers identified student diversity as one of the greatest challenges.2 This concern was reaffirmed by the ten K-12 participating teachers of my doctoral research, who were teaching in public schools in a large urban city in Western Canada. These teachers felt that cultural diversity makes it hard for them to reach their students.

One may take pride in the fact that Canada was the first country that recognized the multicultural nature of its population by establishing a national Multicultural Policy. Since the inception of this policy in 1971, education has been considered the key to address the challenges posed by various dimensions of cultural diversity.3 However, lack of federal control and multiple interpretations of multiculturalism and cultural diversity in various Canadian provinces has resulted in a mosaic fabric of multicultural education that is fragmented and incomplete.4

Often culturally diverse students feel uprooted and unwanted, as their cultural ways of knowing remain unacknowledged and their voices unheard in many Canadian classrooms. Despite claims of multiculturalizing education, the contemporary education system in Canada still privileges Eurocentric, masculine, “white” modes of knowledge as the norm, which only widens the achievement gap for diverse students. Although school policies speak of valuing diversity, the realities of classrooms are often limited to mere “celebration” of cultural ways of knowing in the form of 4Ds: Dance, Dialect, Diet and Dress. Can Canadian teachers, who themselves constantly feel challenged by the growing student diversity, be blamed? How could we change this inequitable landscape of Canadian education, which continues to label “difference” with a deficit-based perspective? Whose responsibility is it?

Education is a collective responsibility. We may hope for a top-down change at the policy level. However, rather than waiting for others, we may begin with ourselves, and think how as educators, we might empower ourselves and our diverse students. One way to do so is by inviting education that is (trans-multi)culturally responsive.

What is (trans-multi)culturally responsive education?

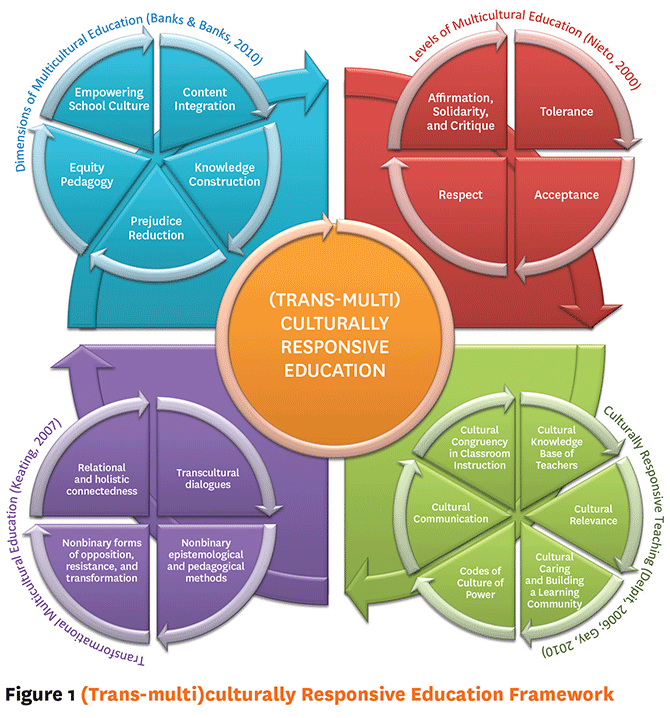

A (trans-multi)culturally responsive education critically examines current practices of multicultural education to unravel the inequities that are embedded in everyday modes of schooling. Guided by critical and transformational multicultural education perspectives5 and Gay’s notion of culturally responsive teaching,6 this education invites teachers to inquire into their own teaching practices and transform these by espousing culturally responsive teaching. Figure 1 illustrates this education framework.

Inviting us to embrace culture as a way of life and cultural diversity as an encompassing aspect of life, a (trans-multi)culturally responsive education calls for beginning with what the students have: their prior knowledges, which may include their cultural ways of knowing, the diversity of their learning experiences, and their self-identified cultural identities. It asks teachers to (re)think: What do we need to “undo” and “unlearn” to (re)create curriculum that is responsive to the multiple needs of today’s diverse students? How might we bring education that educates the heart, mind, body and spirit?7

Envisioning Canadian multiculturalism as jazz,8 where diverse cultural groups’ unique rhythms are recognized as they all come together to create music, this (trans-multi)culturally responsive education invites teachers to think about their students’ culture and cultural identities as continually evolving. Considering the harmony that is crucial to play jazz, it encourages teachers to design their classrooms as (trans-multi)culturally responsive cultural spaces where “difference” among their culturally diverse students is not only tolerated, accepted or respected but valued with affirmation, solidarity and critique.9

Embracing anti-racist, equity pedagogy at its core, this education encourages teachers to become change agents – the cultural brokers and cross-cultural counsellors who are continually working toward dismantling systemic prejudices and establishing an empowering school culture by initiating transcultural dialogues and teaching all students codes of power.10 To translate all these understandings into a reality, it urges teachers to become (trans-multi)culturally responsive educators.

Becoming (trans-multi)culturally responsive educators

Becoming a (trans-multi)culturally responsive educator is an ideological and pedagogical commitment that requires a teacher to first become a (trans-multi)culturally responsive person. There are three main components to this process:

1. Embrace comprehensive understandings of culture and cultural diversity and acknowledge our identity as (trans-multi)cultural human beings. It is essential to acknowledge that culture is a dynamic way of life. Comprised of consciously and unconsciously learned patterns of verbal and non-verbal behaviours, language, values, beliefs, modes of thinking, norms, and socio-political elements of identity, culture continually evolves throughout our lives. It simultaneously constructs us and is constructed by temporal politics and distributions of social power in society. Moreover, each one of us holds multiple cultural identities as we socialize differently into various modes of life. A (trans-multi)culturally responsive education invites us to transcend our individualized cultural identities to relate with each other as (trans-multi)cultural members of one human kin. Hence, when talking about cultural diversity, teachers need to understand that culture does not simply mean differences based on race, ethnicity, nationality or any other fixed identifications, but includes all dynamic cultural experiences that students bring into school.

2. Educate the (w)hole child intellectually, emotionally, socially, and politically by building a community of learners: By utilizing 6Cs: choice, collaboration, communication, critical thinking, creativity and care, teachers can create welcoming, safe and inclusive classroom environments that support (w)holistic learning of all students. Drawing upon Indigenous ways of knowing, they can foster relational connectedness and affirming attitudes, which value cultural differences as potential resources rather than hurdles in learning. By differentiating their instruction and assessments, the teachers can give students choices to learn through multiple sensory modes. To empower students in collaborative co-construction of knowledge, they can begin by strengthening their own and students’ cultural knowledge base. They may do so by inviting students, parents and community members to share their cultural ways of knowing. Thus, by integrating both historical and contemporary cultural resources into classroom learning experiences, teachers can promote creativity, inter-generational learning and cross-cultural communication. They can develop critical thinking and cultural consciousness by deliberately engaging students in transcultural dialogues, which could enable students to critically analyze the information presented and see and understand the differences in their own and other people’s cultures in a respectful, relational manner. In all these processes of learning, it is crucial that teachers embody authentic caring,11 which emphasizes treating others how they wish to be treated, not how we would like to be treated in a similar situation (i.e. realizing that we cannot truly “put ourselves in another’s shoes”).

3. Engage in critical self-reflective inquiries and complicated conversations to co-construct (trans-multi)culturally responsive curricula: Guided by the method of currere,12 teachers can engage in critical self-reflective inquiry about their own biases and prejudices. They can examine how their pre-held assumptions about specific subjects and students’ diversity might lead them to hold misconceptions and take prejudiced actions towards diverse students. For example, often teachers consider science and math as culture-free, neutral subjects. They may also have stereotypical understandings about student diversity such as: All students of a particular culture are good in math. Beginning with themselves as reflective practitioners, teachers can work toward identifying and dismantling the systemic inequities embedded in contemporary modes of schooling. They can initiate complicated conversations to: 1) interrogate what cultural knowledges are missing in the curriculum that is being taught, 2) identify what is being taught as hidden curriculum (such as through bulletin boards, posters and textbooks), and 3) utilize this information to co-construct curricula that is (trans-multi)culturally responsive.

Some examples of (trans-multi)culturally responsive education

How can teachers enact these theoretical understandings with(in) moments of teaching and learning? (Trans-multi)culturally responsive education requires teachers to reflect on their own intentions of teaching and constantly inquire into their pedagogical actions and see how these might have contributed to either perpetuating or preventing the systemic inequities. One such inequity emerged during my doctoral research. The participating teachers claimed that they see their students only as “individuals” and treat all students the “same.” They took pride in acknowledging that that they do not consider students’ culture while teaching.

By contrast, a (trans-multi)culturally responsive educator is cognizant of the fact that seeing students only as “individuals” does not acknowledge their cultural backgrounds. In their efforts to treat all students, the “same,” the teachers may actually perpetuate systemic discrimination by ignoring the difference. For example, when certain female students expressed their discomfort in learning about sexually transmitted diseases and artificial reproductive technologies in a whole-class, mixed-gender Grade 10 setting, the teacher in this case, justified their teaching approach as per the “Canadian curriculum” and with the insistence that they treat all students the “same” as “this is Canada” where most students are fine with discussing such topics.

Many may agree with this teacher’s views, but a (trans-multi)culturally responsive education invites teachers to think and act differently: Would it hurt to consider seeking students’ opinion in advance and to involve them in making certain classroom decisions, such as giving them choices and autonomy to learn about certain topics in individual or group settings? Rather than expecting all students to participate in whole-class discussions and respond to questions verbally, which they may find discomfiting, teachers may consider using online platforms for discussing and assessing students’ learning of these topics. They may also collaborate with community organizations to create opportunities for students to engage with people in a community context and learn these sensitive topics in an authentic, cross-cultural manner.

Differences in students’ socio-economic status (SES) is another characteristic that teachers often do not consider. Again, one may see it as a positive thing. But the issue of ignoring the SES of students becomes problematic when it creates social hierarchies and causes stigma among certain students. For example, it is still a customary practice in many Canadian public schools to send and collect hot lunch and field trip forms through students. Are the teachers aware that students can read their forms and that those whose parents have checked the option requesting financial help, may perceive themselves as inferior compared to the students who are able to pay full cost? This stigma may affect these students’ participation and engagement in learning. Some schools have established online systems where parents can make direct payments. However, the problem persists when teachers give reminders by announcing the names of students who have not paid and/or brought these forms back. This is a structural issue within the school system, and the teachers may not want to communicate with parents about payments or permission slips individually, but they may begin the conversation within their schools and ask: Could there be a way of approaching these parents directly?

Teacher expectations of parental participation in parent-teacher conferences and volunteering may also put certain students on the margins. One may not admit it directly, but often the students whose parents are able to show up for these conferences and volunteer at the school, are regarded with much appreciation by the teachers and school administrators. These students are also reported to have higher self-esteem compared to students whose parents are not able to make it to these events. The teachers may just deal with the matter at the superficial level by sending occasional invitations to these “absent” parents or they may take the challenge to reach out to them on a routine basis. It may sound daunting, but a (trans-multi)culturally responsive education encourages teachers to develop their understandings of different family structures and the diversity of responsibilities that students and their parents may have. It encourages teachers to establish connections with their students and their families, beyond the boundaries of their classrooms. One way to begin might be to hold individual conferences with two or three students each week and to communicate with their families in person or through emails, rotating as needed. Teachers may also approach their school’s multicultural worker and/or parent-teacher association to establish a group where parents of diverse cultural groups may support each other in meeting the needs of their children.

The bottom line is that to reach each and every student in a (trans-multi)culturally responsive manner, it is crucial that teachers make every effort to grow personally, professionally and communally and learn with (and not about) the diverse cultures that they may have in their contemporary diversity-rich classrooms. Further, rather than merely teaching the “prescribed curriculum,” teachers need to engage in a critical self-reflective inquiry by asking: What is missing and/or hidden in the curriculum that we teach in our schools? Why do we need to teach and learn particular concepts? Whose knowledge are we privileging and why? How could we bring diverse cultural knowledges into our contemporary diversity-rich classrooms and co-create knowledge that is (trans-multi)culturally responsive?

Thus, (trans-multi)culturally responsive education is a way of being that involves teaching, learning and living as a (trans-multi)culturally responsive educator. By doing so, we can greet each and every student’s voice with 6 Rs: respect, relevance, reciprocity, responsibility, relationality and reverence for diverse cultures!

Photo: iStock

First published in Education Canada, September 2019

Notes

1 J. Morency, É. C. Malenfant, and S. MacIsaac, Immigration and Diversity: Population projections for Canada and its regions, 2011 to 2036. (Catalogue no. 91-551-X, Minister of Industry, Statistics Canada: January 25, 2017).

2 B. McGahey, “National teacher survey shows diversity as a key challenge in Canadian classrooms,” (news release, Canadian Teachers’ Federation: Jan. 31, 2012). www.ctf-fce.ca/en/news/Pages/default.aspx?newsid=1983984744&year=2012

3 R. Joshee, C. Peck, L. A. Thompson, et al., (2016). “Multicultural Education, Diversity, and Citizenship in Canada,” in J. Lo Bianco, & A. Bal (Eds.), Learning from Difference: Comparative accounts of multicultural education (Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2016), 35-50.

4 R. Ghosh and A. A. Abdi, Education and the Politics of Difference: Select Canadian perspectives (Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc., 2013).

5 J. A. Banks and C. A. M. Banks, Multicultural Education: Issues and perspectives (Hoboken, NJ: 2010); A. Keating, Teaching Transformation: Transcultural classroom dialogues (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007); S. Nieto, Affirming Diversity: The sociopolitical context of multicultural education (New York: Longman, 2000).

6 G. Gay, Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, research, and practice (2nd edition) (New York: Teachers College, 2010.)

7 J. Archibald, Indigenous Storywork: Educating the heart, mind, body and spirit (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008).

8 G. Ladson-Billings, New Directions in Multicultural Education: Complexities, boundaries, and critical race theory, in J. A. Banks and C. A. M. Banks (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Multicultural Education (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2004), 50-65.

9 Nieto, Affirming Diversity.

10 Banks and Banks, Multicultural Education; Gay, Culturally Responsive Teaching; Keating, Teaching Transformation.

11 N. Noddings, “The Language of Care Ethics,” Knowledge Quest 40, no. 5 (2012): 52-56.

12 W. F. Pinar, The Method of “Currere” (paper presented at the Annual meeting of the American Research Association, Washington, D. C.: April 1975).