The Alberta Public Charter School System

A system of secret gardens

In 1994, Alberta Education established Alberta Public Charter Schools as the first of their kind in Canada. The rationale for the establishment of charter schools was to enhance choice and innovation across the province. Alberta Education described the nature of the schools as:

“autonomous non-profit public schools designed to provide innovative or enhanced education programs that improve the acquisition of student skills, attitudes, and knowledge in some measurable way… [They] have characteristics that set them apart from other public schools in meeting the needs of a particular group of students through a specific program or teaching/learning approach while following Alberta Education’s Program of Studies.”[1]

Alberta Public Charter Schools operate under agreements or “charters” with the Minister of Education for the establishment, administration, and renewal of the charter school. The charter describes the unique educational service the school will provide, how the school will operate, and the intended student outcomes. Charter schools are given more autonomy in governance and program delivery than other public school jurisdictions in the province, so long as the school can demonstrate: (1) innovation in education and (2) improved student learning. Their governance also differs from public or separate school jurisdictions. Unlike most public school jurisdictions, each charter school has its own principal, board and superintendent. Initially, charter schools received a five-year agreement from the Minister of Education. More recently, charter schools have been permitted to apply for a 15-year charter agreement. To support each charter school, the Association of Alberta Public Charter Schools (TAAPCS) was established to promote public charter school education in Alberta, play an advocacy role, and promote continued innovation and choice within public education.[2]

In this article, we provide an overview of the nature of Alberta Public Charter Schools, and offer a sampling of findings from a comprehensive study of the TAAPCS system to address two “myths”:

- Alberta Public Charter Schools have more freedom to do what they want to do, and

- Alberta Public Charter Schools are unfairly competing with the public system.

Why parents choose charter schools

Charter schools have proved a popular option in Alberta; for each of the nearly 8,000 students enrolled in 13 Alberta Public Charter School jurisdictions, another student’s name rests on a lengthening enrolment waitlist. Parents are attracted to charter schools for a variety of reasons:

- the desire for greater input and control in determining the education for their children

- a greater chance to find like-minded parents and staff with a common educational goal

- the sense that the mainstream schools cannot meet their child’s specific learning and/or developmental needs

- the belief that charter schools can be more responsive and flexible to changes within the school, with fewer bureaucratic constraints than are found in larger school districts

- they agree with the educational vision and mission of the school

- they feel a greater sense of belonging and community.[3]

Parents who wish to send their children to charter schools have also identified some challenges:

- long wait lists

- few charter schools exist in rural areas

- potential transportation constraints

- limited resources to attend to all diverse needs of children.

Controversial aspects of Alberta Public Charter Schools

Early debates about the implementation of Alberta Public Charter Schools were, and in some respects remain, politically contentious. Critics of charter schools framed it as a form of publically funded private education. This is not surprising, given that in the mid-1990s, strong market-driven educational reforms were prevalent in Alberta and internationally.[4]

More controversially, charter school teachers – unlike public school teachers – are associate rather than full members of the Alberta Teachers’ Association (ATA). This designation was of particular concern to the ATA regarding the full protection of teachers within schools and the potential weakening of their position across the province.

There was further scepticism regarding the inclusivity and equitability of students and families who chose charter schools. Critics felt that the educational mandate would target students perceived to be preferable, due either to their talents or to socio-economic factors. Concerns arose around admissions processes, and the parameters of the educational mandates that could potentially exclude certain children from being considered.

Some of these early debates have been resolved with greater understanding, although discussions still emerge regarding the schools’ legitimacy, innovation, and impact on the larger educational landscape.

Alberta Public Charter Schools

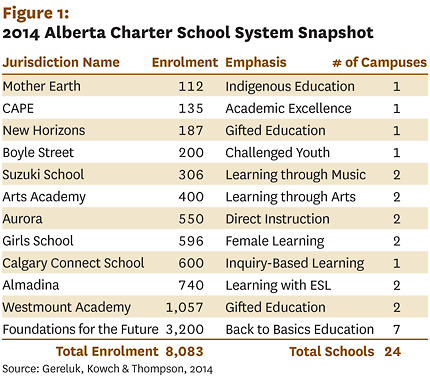

Most Alberta charter schools are located in Calgary and Edmonton. Currently, thirteen charter schools serve different student populations and diverse needs in the Province of Alberta (see Figure 1).

The schools are not restricted to students perceived as “easy to teach,” as may be charged by critics. They incorporate a distinct range of students. However, unlike public schools, charter schools do not receive additional funding for students who may have an Individual Program Plan (IPP) identifying diverse cognitive, emotional, social or behavioural needs. This may limit the range of students accepted into charter schools beyond their educational mandate.

New research about the Alberta Public Charter School system

Numerous studies have been conducted at the micro-level within particular charter schools,[5] but little research has been conducted at the macro-level considering the entire TAAPCS association. In a recent study,[6] we examined Alberta Public Charter Schools on a macro-level. We focused particularly on their ability to adapt and change education, by asking stakeholders to indicate the most influential issues consuming their interests and to identify the people and organizations important in solving their most pressing challenges. We also considered TAAPCS’ internal and external impacts to the broader educational jurisdictions. The resulting snapshot of the Alberta Public Charter School system illustrated a complex mix of the most pressing issues and networks of relationships found within, across and beyond Alberta Public Charter Schools. In this article, we unpack two dominating misunderstandings or “myths” and offer evidence from our research to reconsider the nature of Canada’s only public charter school system.

Myth #1: Alberta Public Charter Schools have more freedom to do what they want to do.

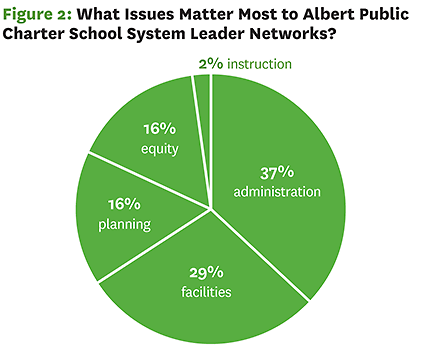

Freedom and autonomy: Alberta Public Charter Schools have the freedom to: 1) provide a specific education focus, and 2) govern through their own administrative and teaching processes. However, when we looked at the entire charter school system network of self-identified influential superintendents, teachers, board leaders, community members and government leaders, we identified several severe constraints on freedom and autonomy of leadership across this school system. We found that system leader networks invest 37 percent of their energy in administration and 29 percent in facilities issues, while spending only 16 percent on planning, 16 percent on equity and 2 percent on instruction issues. While individual schools have freedom to “do what they want” with regards to diverse program emphases and innovation, nearly half (44 percent) of their efforts are disproportionately focused on administration and facility issues, because external student access and space pressures (waitlists) have become primary leadership issues (see Figure 2).

Government agents in charge of facilities form the few critical links between leaders among the schools, limiting the power of the overall leadership network to invest their considerable resources in other issues. As one leader said:

“We don’t have facilities; you can’t grow without facilities. We don’t really create a choice for families in Alberta to go to charter schools because there is no available space there to come into.”[7]

Alberta Public Charter School leaders face limited facility availability (space), so they invest a vast proportion of their time in infrastructure issues. Provincial government education regulations require each school to negotiate for additional space with nearby public boards before they can: 1) acquire old public system spaces or 2) build new spaces. TAAPCS leaders must also negotiate with provincial government infrastructure agents for building capital in an intensely competitive provincial population growth picture. As a system, TAAPCS demonstrates a relatively low level of freedom to organize its interests in the face of change.

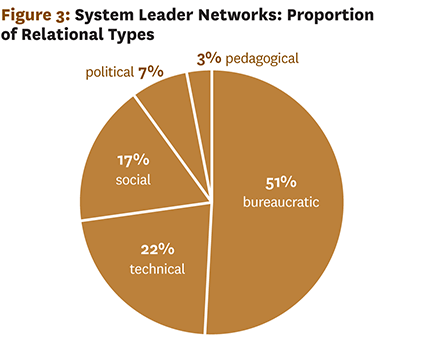

Doing the things they want to do: Research by Goldstein, Hazy, and Lichenstein revealed that certain patterns of relations among school community members (teachers, leaders, parents, students, and government) increase the potential for one part of the system to positively impact all other parts so that a system can “do” what it wants. A lot of good relationships form flexible networks on the basis of shared common values, social supports and trust. When those features trump technical, power and even knowledge-based relationships, a school system becomes more adaptable.[8] By contrast, hierarchical, vertical power-based relationships shown in classic “org charts” are the most brittle forms of organization. Figure 3 demonstrates a majority of bureaucratic and technical relationships among charter school system leaders.

In our study, we analyzed all relational networks and discovered a diffuse, fragmented pattern of leader connections between charter schools and tighter, closed clusters of relations within each school. These clusters indicate a system leader network with dominantly hierarchical, bureaucratic relation types. These types of systems generally lack flexibility or “freedom to do what they want.”

For the Alberta Public Charter School system to “do what it wants,” it needs to connect more among schools, across schools and beyond charter schools, similar to the enduring, deep relationships currently developed between some charter schools and community and business members. Students, nearby school systems (boards), government agents outside the charter administrative group, national and international organizations, professional teacher associations (the ATA) and leader associations (College of Alberta School Superintendents) are generally missing from the current networks.

Myth #2: Alberta Public Charter Schools are competing with the public school system

Currently, Alberta Public Charter School enrollment stands at less than one percent of the total school-aged population in Alberta. The public charter school concept has neither “taken off” as a disruptive innovation in Canada, nor has it threatened public schools more broadly.

Defining competition: Zimmer and Budin[9] defined competition in education as a dynamic in a closed market system where tensions exist among education providers because resources (students) can migrate among school institutions. Given that any school outside a catchment-based, policy-mandated attendance rule is potentially “in competition” with others, Myth #2 could be true on a surface level. To a certain extent, all public schools are in competition with each other.

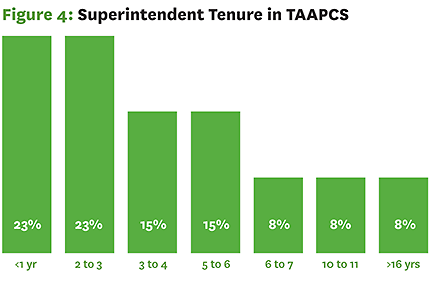

Competing with the public system: For the Alberta Public Charter School system to make a competitive impact on the larger public education systems, the organization would require a long-term plan and concerted action to attract students from outside its system.[10] Our research revealed that TAAPCS leaders lack a collective connection to the world outside the TAAPCS, and we found no evidence that they are actively competing with other school systems. This could be because TAAPCS leaders are turning over quite quickly – while they are very experienced as a group, over 75 percent of them have practiced in the charter system for less than six years (See Figure 4). Long-term marketing/competition plans would be difficult to actualize across the system with high turnover. Furthermore, we found that less than 20 percent of the leadership network efforts were concentrated on system-level change or impacts. Further, 76 percent of the leaders identified the target of their “impact work” to be impacts within charter schools, and not impacts external to the charter schools.

Although Alberta Public Charter Schools are successful as a collection of diverse and innovative schools, they are not as free or agile as many think when pursuing what they want to do as a collective of schools.[11] These schools have evolved over two decades into something of a set of “secret gardens” with an inward focus. Schools have strong internal impact within the boundaries of their schools, but show less external impact across the province. Further, charter school stakeholders describe a difficulty in sharing their educational practices with other school jurisdictions, given some animosity, tension and misperceptions of TAAPCS. They remain fairly disconnected from other education systems or professional educational bodies.

With limited connectivity between and beyond each charter school, no overall strategic plan for marketing, high leader turnover rates, and leader-targeted change programs impacting only other charter schools, the Alberta Public Charter School system is not a major competitor with the public system. TAAPCS does, however, offer important experience, governance, community engagement, structural and pedagogical innovation examples that could improve provincial education system adaptability.

The impact of Alberta Public Charter Schools on the education system as a competitive force is far less than many believe. That said, with the development of more open policy environments and collaboration across education systems in Alberta, this alternative system may offer promise for increasing the capacity of all education organizations in a changing Alberta.

En Bref : L’environnement éducatif albertain change. Le seul système d’écoles publiques à charte du Canada compte maintenant près de 8 000 élèves inscrits et beaucoup d’autres sur des listes d’attente. Cet article présente une vue d’ensemble de la nature des écoles publiques à charte de l’Alberta et certains des constats d’une étude exhaustive du système réalisée par l’Association of Alberta Public Charter School (TAAPCS) pour dissiper deux « mythes » : 1) les écoles publiques à charte de l’Alberta sont plus libres de faire ce qu’elles veulent; 2) les écoles publiques à charte de l’Alberta concurrencent inéquitablement le système public. En raison des cadres de politiques, des malentendus concernant les écoles à charte et des liens limités entre la TAAPCS et le reste du réseau public, ses innovations demeurent une sorte de « jardin secret » enclavé, tourné vers l’intérieur. Ces écoles ont un fort impact interne dans leurs établissements mêmes, mais un faible impact externe dans la province.

Collage: Dave Donald

First published in Education Canada, June 2016

1 Alberta Education, Charter School Handbook (Edmonton: Alberta Education, 2011), pg. 1. https://archive.education.alberta.ca/media/434258/charter-schools-handbook-september-2015.pdf

2 For a full explanation of the role of the Association of Alberta Public Charter Schools, see www.taapcs.ca

3 Lynn Bosetti and Dianne Gereluk, Understanding School Choice in Canada (Toronto: Toronto University Press, 2016).

4 Lynn Bosetti, “The Dark Promise of Charter Schools,” Policy Options 29, no. 6 (2014): 63-67.

5 For a complete list of the internal research projects that have been conducted in Alberta’s Public Charter Schools, please see: www.taapcs.ca

6 Dianne Gereluk, Eugene Kowch, and Merlin Thompson, The Impact, Capacity and Adaptability of the Alberta Public Charter School System (University of Calgary, 2014).

7 Arnold, cited in Gereluk, Kowch, and Thompson, 2014, p. 155.

8 J. Goldstein, J. Hazy and B. Lichtenstein, Complexity and the Nexus of Leadership: Leveraging nonlinear science to create ecologies of innovation (Palgrave MacMillan, 2010).

9 R. Zimmer and R. Budin, “Is Charter School Competition in California Improving the Performance of Traditional Public Schools?” Public Administration Review 69 (2009): 831-845.

10 T. M. Davis, “Charter School Competition, Organization and Achievement in Traditional Public Schools,” Education Policy Analysis Archives 21, no. 88 (2013). http://epaa.asu.edu/ojs/article/view/1279

11 M. Uhl-bein, R. Marion, and B. McElvey, “Complexity Leadership Theory: Shifting leadership from the industrial age to the knowledge era,” The Leadership Quarterly 18, no. 4 (2007): 298-318.