Overcoming Reading Deficits

Implementation of a Tier-3 reading intervention in the Toronto Catholic District School Board

The Toronto Catholic District School Board (TCDSB) introduced EmpowerTM Reading (henceforth, Empower) to address the ongoing needs of exceptional students with reading difficulties.

Over 30 years ago, TCDSB partnered with Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) to introduce Empower in its developmental phase (Lovett & Steinbach, 1997). TCDSB continues to use Empower’s commercial version in up to 100 classes, located in 70+ schools; numbers vary slightly by year.

The TCDSB-SickKids’ partnership occurred when the whole-language approach was influential in shaping educational practice in Ontario. Its opponents, however, presented counter-evidence that basic pre-requisite skills, including phonemic awareness, reading fluency, and vocabulary development (Nathan & Stanovich, 1991), are critical in improving automaticity in decoding and reading, necessary before learning higher-level skills. Persistent deficits in basic word identification skills require direct remediation of phonologically-based reading skills, systematic and explicit instruction in letter-sound and letter cluster-sound mappings, and reinforcement of word identification learning (Rayner, et al., 2001).

TCDSB’s involvement in Empower development began when the identification of learning disabilities was based on the now-defunct model of IQ-achievement discrepancy. Current practice across Ontario school-boards focuses instead on the “psychological processes” underlying a learning disability, of which phonological processing is one. It involves the awareness of phonemes – the alphabetic principle that underlies our system of written language. Specifically, developing readers need an understanding of the internal structure of words to benefit from formal reading instruction (Adams, 1990). Once decoding is efficient, attention and memory processes are freed for comprehension. Phonological awareness therefore assumes a pivotal role in learning to read. It is a strong predictor of a child’s literacy development (Melby‐Lervåg et al., 2012), from Kindergarten throughout school (Perfetti et al., 1987; Calfee et al., 1973).

The Empower program addresses learning problems of struggling readers by remediating core deficits in decoding, spelling, word-reading, vocabulary development, and text comprehension. The program’s initial focus on letter-sound identification and sound-blending training gradually moves to larger sub-syllabic units such as phonograms, vowel clusters and affixes, each with its own metacognitive strategy.

To address reading difficulties confronting special education students, TCDSB deploys Empower as a Tier-3 reading intervention, targeting those with a Learning Disability (LD)/Language Impairment (LI) learning profile for whom previous Tier-1 & 2 interventions (e.g. 5th Block) have been unsuccessful. The main admission criteria are:

- The student is formally identified as LD/LI, or being assessed/tracked for LD/LI difficulties

- The primary presenting concern is difficulty in decoding and/or word identification, or text comprehension, as appropriate for the program being considered

- The student has an Individual Education Plan (IEP)

- Consistent attendance, and ability to participate without disruption

TCDSB implementation model

Select TCDSB elementary schools host Empower program(s), with mandatory training by SickKids-appointed staff, accountability/research tracking, and centralized monitoring/management by the TCDSB Empower Steering Committee. Comprised of interdisciplinary representatives, the Empower Steering Committee oversees program implementation.

With authorization from SickKids, highly experienced TCDSB-appointed special education teachers monitor the fidelity of implementation by serving as internal mentors/trainers. There are two initial training days for teachers, further training during the year, and subsequent refreshers. The mentor provides scheduled classroom visits and consultation via phone/e-mail. Training focuses on instructional methods, Empower lesson components and materials, student monitoring and assessment.

When interviewed, teachers were very pleased with the initial training (despite its intensity) and support/feedback from mentors’ classroom visits.

About half of the 70+ participating schools were selected as Empower “Hubs,” receiving additional staffing allocation. Eligible students from non-Empower schools could transfer to a nearby “Hub” for one year and receive instruction in Empower and all other subjects. Teachers consistently reported that transferred students made academic and social progress similar to other Empower students.

We focus on Empower Decoding/Spelling for Grades 2 to 5. More than 100 60-minute lessons are taught to about 500 students in small classes of 4–7. In addition, the Board recently implemented Decoding/Spelling for Grades 6 to 8, and Comprehension for Grades 3 to 7.

To address core deficits in decoding and spelling, students receive instruction in five decoding strategies in sequence:

- Sounding Out (a phonological letter-sound decoding strategy)

- Rhyming (word identification using known keywords to decode unknown words with the same spelling patterns)

- Peeling Off (stripping prefixes and suffixes from multisyllabic words to get a smaller root, which then can be decoded using one of the other strategies)

- Vowel Alert (trying variable vowel pronunciations according to their frequency

- Spy (seeking familiar parts of unfamiliar words).

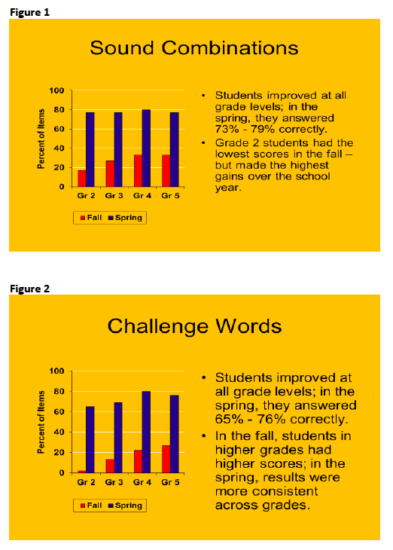

On several letter-sound and word-identification tests, most students made substantial gains in decoding (see examples in sidebar). Students read more in class or at home and were positive about their reading ability. Students admitted to Empower while waiting for assessment for LD/LI difficulties made good progress with Empower. Often they ended up not meeting the requirements of a formal identification, or no longer required a formal IEP. Some formally identified LD students and most LI students made progress, but less so than other students. Others made limited progress because of poor attendance and behaviour, reinforcing the requirement to address these issues before Empower. The behaviour of some students improved after success in decoding.

Teachers recommended that 20–40 percent (depending on the measure/report) of students receive additional reinforcement after Empower to help them cope with reading in higher grades.

Empower teacher feedback

Empower teachers were interviewed/surveyed every year on implementation of Empower. Often, they reported successful implementation. Some problems were often resolved in the first year; others persisted and required central intervention.

When Empower classes first rolled out, staff were pressured to place English-as-a-Second-Language (ESL) and Mild-Intellectual-Disability (MID) students in their classes, as well as students with behavioural and attendance issues. Some teachers had classes of students with varying grade levels and needs. By the following year, however, school administrators corroborated with teachers to adhere to admission criteria, but problems around behaviour and attendance persisted. In response, the Empower Committee provided written instructions to principals, followed by specific procedures to centralize annual screening.

Initially, about 40 percent of classes did not finish the program in one school year, often delaying the class that followed. The Empower Committee therefore required all new classes to begin in September. As a result, classes now finish on time, except under exceptional circumstances (e.g. long-term teacher illness).

At the outset, first-year teachers reported needing 70+ minutes per class. More experienced teachers generally completed instruction in 60 minutes or less.

As the program progressed, most Empower teachers met with regular/special education teachers, often informally, to discuss Empower lessons and students’ needs/progress. Classroom teachers were encouraged to have Empower students read in class and at home. Teachers discussed collaboration on assessment and sharing results, especially when Empower teachers were not familiar with Primary assessment. Support from the principal was essential, especially in addressing scheduling and collaboration. Sometimes, diplomatic negotiation was needed to schedule Empower, mandatory classes taught by itinerant teachers (Gym, French), and major subjects like Math. Empower is fast-paced, requiring uninterrupted class time without announcements, school activities or professional obligations. After the first year of Empower, such interruptions were rare.

Parents were expected to meet the Empower teacher as part of the admission process. Students were encouraged to read at home and discuss passages with parents. On interview night, about half of parents met with teachers who provided them with information on Empower and homework. Some parents were highly cooperative; others less so.

The Empower program requires a strong commitment to implement effectively. However, we feel the results attest to the program’s worth. This success is not only determined by assessment, but by continuing positive feedback obtained from stakeholders that Empower has indeed changed students’ lives and positively impacted their learning. As one Grade 3 student put it: “Thank you for making Empower. I couldn’t even read a book that was easy. I can read books that are chapter books AND 24 pages long!” Parents are equally enthused, as one described her experience: “This program has not only helped my son to learn how to read but also improved his self-esteem. He doesn’t have to pretend to know how to read anymore; he knows that he can actually do it.” Teacher and school administrators are similarly highly motivated to host Empower, as in one principal’s feedback: “The Empower program has made a profound difference to the lives of many students. Students become strategic and successful readers. Over 12 years, I have witnessed the transformative power of the Empower program.” Perhaps what is most rewarding to teachers, frontline staff and the interdisciplinary professionals running Empower is the affirmation that scientifically-based and well-executed remediation programs have a key role to play in the eradication of illiteracy in our 21st century learning, to forever change the lives of children and their families for the better.

References

Adams, M. J. (1990). Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. Bolt, Beranek, and Newman, Inc.

Calfee R.C., Lindamood, P., & Lindamood, C. (1973). Acoustic-phonetic skills and reading–kindergarten through twelfth grade. J Educ Psychol. 1973 Jun, 64(3):293–298.

Lovett, M. W., & Steinbach, K. A. (1997). The effectiveness of remedial programs for reading disabled children of different ages: Does the benefit decrease for older children? Learning Disability Quarterly, 20(3), 189–210.

Melby-Lervåg, M., Lyster, S.-A. H., & Hulme, C. (2012). Phonological skills and their role in learning to read: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 138(2), 322–352. doi.org/10.1037/a0026744

Nathan, R. G., & Stanovich, K. E. (1991). The Causes and Consequences of Differences in Reading Fluency. Theory into Practice, 30(3), 176–183.

Perfetti, C. A., Beck, I., Bell, L. C., & Hughes, C. (1987). Phonemic knowledge and learning to read are reciprocal: A longitudinal study of first grade children. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 33(3), 283–319.

Rayner, K., Foorman, B., Perfetti, C. A., Pesetsky, D., & Seidenberg, M. S. (2001). How psychological science informs the teaching of reading. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 2, 31–74.

Acknowledgments:

The research described in this article has previously been reported to various TCDSB committees. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions/policy of the TCDSB.

The authors wish to express their gratitude to Dr. Maria Kokai (TCDSB), Dr. Marina Vanayan (TCDSB), and the SickKids’ LDRP Team for their guidance and advice. The successful implementation of Empower was only made possible by the vision and firm support of the TCDSB Superintendents of Special Services, past and present, as well as the professionalism and hard work of the many Empower teachers, the Empower Steering Committee, mentors/trainers, and Special Services staff who dedicate their time and career to better the lives of children under our care.