The Path to Bilingualism

The Common European Framework for languages in Canada

An objective of the federal government’s action plan for official languages is to double the number of high school graduates who have functional knowledge of the second official language. This goal is generally shared by stakeholders at all levels of language education, and for good reason: There are many advantages to being bilingual. Bilingualism enhances divergent thinking, memory, reasoning and problem-solving abilities; awareness and appreciation of different cultures; as well as flexibility, adaptability and openness in attitudes.

An objective of the federal government’s action plan for official languages is to double the number of high school graduates who have functional knowledge of the second official language. This goal is generally shared by stakeholders at all levels of language education, and for good reason: There are many advantages to being bilingual. Bilingualism enhances divergent thinking, memory, reasoning and problem-solving abilities; awareness and appreciation of different cultures; as well as flexibility, adaptability and openness in attitudes. These are desirable qualities for Canadian citizens to share collectively, and they also enhance our creative, innovative potential to participate successfully as a nation in the global economy.

What is bilingualism?

Clearly having a bilingual population is a valuable asset. Yet what is bilingualism? According to federal documents, bilingualism is “the ability to speak two languages”[1] – but what does this actually mean? Is someone who can order coffee in French considered bilingual? Or does the person need to be able to participate in a job interview or discuss complex issues? Without a generally accepted meaning, how do policy makers, administrators, and teachers know if and when students have reached the goal of being bilingual?

Yet a narrow definition for bilingualism is not the solution. Just as not all students will attain the same level of language ability, not all students have the same linguistic needs. A student who wishes to work in the federal civil service requires more advanced communicative skills than the one who merely wants to travel in Quebec. In other words, the many different contexts of language use require different content, focus, and outcomes in learning.

The answer lies not in defining bilingualism but in describing language proficiency more broadly, in a way that reflects how languages are learned and used, includes different levels of attainment and learning contexts, and can be taught and assessed effectively. Why would such a definition of proficiency be helpful? Imagine that it would be possible to:

• Know students’ language level at every point of their learning process – from Grade 4 Core French to Grade 12 French Immersion to public service training and beyond;

• Design and deliver programs suited to students’ levels and needs – from French for working in a restaurant to French for studying at a bilingual university to French for becoming a language teacher;

• Use evaluation tools that track students’ language progress in a way that all educators understand, so that a “B1 level” in spoken interaction means the same in Ontario as it does in British Columbia;

• Organize language instruction according to level rather than grade, so that a student from New Brunswick at Grade 7 A2 level can be transferred to a Grade 8 A2 level classroom in Saskatchewan;

• Relate students’ levels to language learners within and across institutions, so that a student who finishes a federal language course (Explore) at B2 level in Quebec can be considered for admittance to a bilingual university in Canada;

• Relate students’ levels worldwide – meaning an A2 level student in Manitoba can “do” the same communicative tasks in French as an A2 level student in Germany.

Defining bilingualism in a framework

The possibilities listed above are offered by the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR), or “the framework.” Developed by the Council of Europe in 2001, the framework created common terminology so that practitioners in all 47 member states could collaborate to create and compare educational policies, programs, and qualifications. It offers a system to describe and measure language proficiency in a broad way. The use of the CEFR has extended beyond the borders of the EU to include countries such as Brazil, Australia, Japan, and China.

The framework was introduced in Canada in 2006, thanks in large part to the work of the Canadian Association of Second Language Teachers (CASLT). The CEFR is also supported by the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada (CMEC), as it can assist in creating a coherent system of language education across the country.

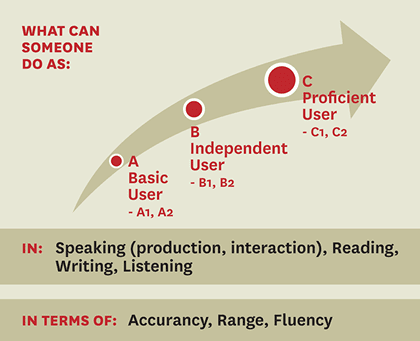

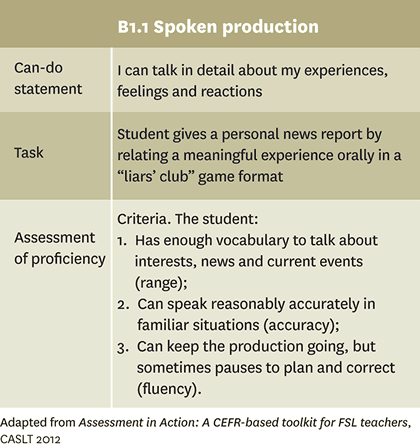

Briefly, the framework provides scales of language use across a continuum of three global levels (A to C) that are further divided into six sub-levels (A1.1, A1.2 to C2.2). Illustrators (called “can do” statements because of their wording) describe what language learners at the different proficiency levels can do in tasks of writing, listening, reading, speaking, and interacting with others. Language performance is assessed by sets of criteria that describe the quality of the performance, such as writing a report, responding to a written text, expressing an opinion, etc.

The benefit of using this framework is that it is:

- Comprehensive: can be applied to different curricula and language programs;

- Flexible: can be adapted to suit the varied language needs and contexts across the country;

- Grounded: based on a commonly accepted theory of language teaching, learning, and assessment;

- Validated: supported by more than 30 years of rigorous research into language teaching, learning, and assessment;

- Recognized: used in over 47 countries;

- User friendly: “can do” statements can be understood and used by administrators, teachers, testers, curriculum developers, and students alike.

What does the framework look like?

How is the framework used in Canada?

British Columbia additional languages curriculum

Federal language bursary program (Explore) CEFR curriculum alignment for St-Jean Campus

What is it? The Explore program, offered by the University of Alberta’s St-Jean campus in La Pocatière, Quebec, aligned its program goals, language levels, and teaching and assessment practices with the CEFR. A toolkit published by CASLT was used to assist language instructors to teach and assess students’ levels using the framework. The aim of the project was to serve as a model for the other 45 Explore institutions across Canada, who wish to align their curricula and programs with the CEFR.

How does it work? The 250 summer students’ language levels were assessed at the beginning of the five-week intensive course with a language test and interview. The students were placed in groups according to their CEFR level. The instructors received guidance to learn about the framework and to adapt and use the CASLT materials to suit their students’ language needs. Students filled in self-assessments and used language portfolios to track their learning throughout the course. The students were assessed for their progress during and at the end of the course to establish their program exit level within the framework.

Future of the CEFR in Canada

The framework provides the means to define and measure proficiency. This is a necessary basis for knowing what constitutes being bilingual and whether the goal of doubling the number of bilingual students has been met. The framework also does much more than that: it defines proficiency in a way that takes into account different language needs, contexts, levels, curricula, and programs across institutions, provinces, and countries. As such, the framework is a valuable tool that has useful implications for second-language education across Canada.

First published in Education Canada, January 2013

Resources

Assessment in Action: A CEFR-based toolkit for FSL teachers (2012) can be ordered from the Canadian Association of Second Languages website: www.caslt.org. Also available in French.

EN BREF – L’un des objectifs du plan d’action fédéral en matière de langues officielles consiste à doubler le nombre de diplômés du secondaire ayant une compétence fonctionnelle de leur deuxième langue officielle. Pourtant, sans définition claire du bilinguisme, ou sans même une approche cohérente de l’évaluation des connaissances linguistiques, comment peut-on déterminer si cet objectif a été atteint? Cet article définit et présente le Cadre européen commun de référence pour les langues (CECR). Ce cadre constitue non seulement un moyen pour décrire et évaluer la compétence linguistique de telle façon qu’elle reflète comment la langue est apprise et exploitée, mais sert également à élaborer un système cohérent d’enseignement des langues à l’échelle du pays. Deux projets cités démontrent l’utilité du CECR en tant que ressource ayant des implications utiles pour l’enseignement d’une langue seconde au Canada et, ainsi, pour réaliser l’objectif d’accroissement du nombre de diplômés bilingues.

[1] Treasury Board Canada Secretariat, Official Languages Policy Framework (2004). www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/pol/doc-eng.aspx?id=12515§ion=text#appA