The Gift of Positive Space Groups:

A Transformation for LGBTQ Students

A colleague recently asked me, “Which situation makes you more anxious – presenting to high school students or to the police?” I didn’t have to think twice. “Definitely high school students!” I present to both groups regularly now, but it hasn’t always been that way.

Last September, I started having weekly conversations with Hamilton Police Services about Creating Positive Space for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Queer (LGBTQ) people. It’s part of their block training, and by the time we wrap up in June, all 800 or so civilians and sworn officers will have had a chance to explore this topic, both as individuals and as an organization.

I am also often asked to speak to high school students about creating LGBTQ Positive Space Groups (PSGs) in their learning environments. That started in 2010, after I compiled a manual for students, teachers, and administrators to assist with implementing PSGs in the Hamilton-Wentworth District School Board (HWDSB), an initiative of then Director of Education, Chris Spence. Of the 18 secondary schools in the Hamilton-Wentworth District School Board, 17 now have PSGs.

Lately however, I’ve had to rethink the anxiety question. The more I assist LGBTQ students in initiating PSGs in their secondary schools – along with their ally classmates and teachers – the more my anxiety dissipates. It’s not just because I’m getting used to the experience; it’s because the response to the conversation is so powerful. The students are more anxious than I am because they’ve been waiting to talk openly about their lives for a long time. Once I say the word “lesbian” or “queer” out loud, it’s as if I’ve given permission for the floodgates to open.

I recently showed up at McKinnon Park Secondary School in Caledonia, Ontario expecting two or three teachers and a handful of students to talk about how to get a group going. Instead, there were nine teachers and almost 30 students. Everyone was eating lunch, and I was nervous, wondering whether I’d be able to pull their attention away from food and fun chatter. However, after a few opening remarks you could hear the proverbial pin drop, and once I opened it up to hear whether homo/bi/transphobia was a reality in their school, community, or families, the sharing was tremendous. One of the lead ally teachers later remarked that she’d never heard students speak so candidly about what they or others were facing because of LGBTQ oppression.

That’s the gift, for both LGBTQ students and their allies; PSGs transform an educational site. LGBTQ teachers, who are often closeted, feel the impact, too, so the benefits can go even further afield.

What is Positive Space, Anyway?

LGBTQ Positive Space Groups (PSGs) are intended to help create a school that

- is free of discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identities;

- allows all students to feel included and welcomed so they may focus their energies on academic objectives as well as partake in school social life and co-curricular activities;

- allows all members of the school community to feel welcomed and included in order to create positive learning and workplace environments;

- decreases fear and disapproval of sexual and gender diversity;

- encourages inclusion of LGBTQ peoples’ lives, politics, culture, families, and histories in curricula, course offerings, and research opportunities.1

The term Positive Space was coined in 1996 at the University of Toronto in response to a homophobic assault on a professor. A module of training on LGBTQ realities was developed, and all participants – faculty, staff, and students – received a sticker with the newly created Positive Space symbol: a mash-up of the rainbow flag and the inverted triangle that was used to mark LGBTQ people during the Holocaust.

A Rose by Any Other Name

While the term Positive Space Group has been promoted here in Hamilton, the majority of groups in the U.S. and Canada are identified with the moniker Gay-Straight Alliance (GSA). However, GSA is problematic under an anti-oppression framework because “gay” does not necessarily refer to lesbian, bisexual, or trans-identities and can, therefore, been seen as exclusive.

In the end, since the groups are primarily started by and for LGBTQ students, it is best when they name them in a way that resonates for their own school community. However, it is important that the name reflect the fact that the groups are specifically for LGBTQ students and are not meant to address diversity in some broader way.

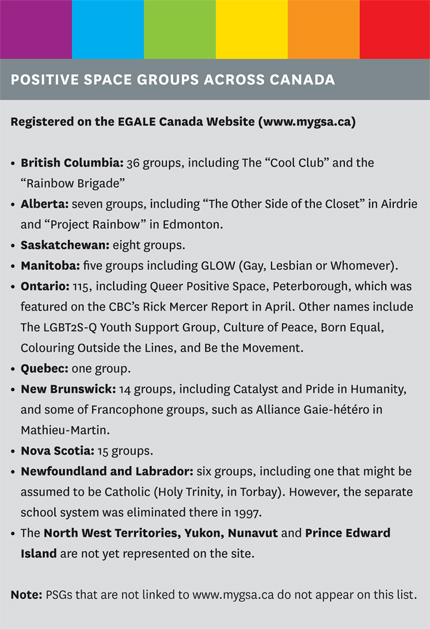

Equality For Gays and Lesbians Everywhere (EGALE) Canada launched a website (www.mygsa.ca) in 2010 to help connect PSGs across Canada. The site also provides resources for educators and parents and identifies 220 groups from coast to coast. PSGs are encouraged to register and provide information about their particular group. Approximately 125 of the groups have GSA in their names, as it is still the most commonly used term. See the sidebar for a province-by-province summary of groups – including some creative names – registered on the EGALE website.

Some of these PSGs have an online presence while others are invisible when searching through student club lists. Pauline Johnson Collegiate and Vocational School in Brantford has a Positive Space symbol right on its homepage with a link to information about upcoming PSG meetings, teachers you can talk to about the group, and some great video links. Rainbow Alliance at a Vancouver school has a video from its 2012 Pink Project, where 1,500 students from Vancouver danced to Lady Gaga’s “Born this Way”.

Not all schools and school systems have been receptive to the concept of PSGs. Premier Dalton McGuinty’s introduction of an amendment to the Education Act to make GSAs mandatory in all Ontario secondary schools, public and Catholic, sparked intense debate in the Separate School system. The response from the Catholic boards has been to ban any reference to sexual orientation or “rainbow” in the group name, and to allow only groups that focus on broader diversity issues.

Benefits for Both LGBTQ Students and Allies

The isolation experienced by LGBTQ youth, who are closeted in all or parts of their lives, leads to a higher rate of alcohol and drug use, smoking, mental health issues, and suicide.2 In a focus group with 15 youth for a Needs Assessment on LGBTQ people in Hamilton, three had already attempted suicide because of feelings of isolation. Although the research to date has been limited on this population in general, national studies in the U.S. and Canada show that LGBTQ youth are three to six times more likely to commit suicide than their straight counterparts and that 30 percent of all completed youth suicides are related to issues of sexual identity.

The isolation experienced by LGBTQ youth, who are closeted in all or parts of their lives, leads to a higher rate of alcohol and drug use, smoking, mental health issues, and suicide.

The Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN) has been conducting an annual National School Climate Survey in the U.S. since 1999. In 2009, they reported on the experiences of 7,261 middle and high school students and found that nearly nine out of 10 LGBTQ students experienced harassment at school in the past year, and nearly two-thirds felt unsafe because of their sexual orientation. The survey results verified that homophobia and transphobia are having detrimental impacts on student achievement and academic success.

The good news was that students in schools with GSAs reported hearing fewer homophobic remarks, experienced less harassment and assault because of their sexual and gender orientation, and were more likely to report incidents of harassment and assault to school staff. They were also less likely to feel unsafe because of their sexual orientation or gender expression, were less likely to miss school because of safety concerns, and reported a greater sense of belonging to their school community.

A homophobic environment has an impact on academic performance, as well. The reported grade point average of students who were more frequently harassed because of their sexual orientation or gender expression was almost half a grade lower than for students who were less often harassed. There is no reason to believe that the experience of LGBTQ youth in Canada would be much different in any of these areas.

In fact, EGALE Canada has replicated some of that research in its first national study in 2011, “Every Class in Every School: The First National Climate Survey on Homophobia, Biphobia, and Transphobia in Canadian Schools”. Both LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ students completed the survey.

- Almost two thirds (64 percent) of LGBTQ students and 61 percent of students with LGBTQ parents reported that they fell unsafe at school.

- The two school spaces most commonly experienced as unsafe by LGBTQ youth and youth with LGBTQ parents are change rooms and washrooms.

- 70 percent of all students (LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ) reported hearing expressions such as “that’s so gay” everyday in school and almost half (48 percent) reported hearing remarks such as “faggot,” “lezbo,” and “dyke” everyday in school.

- Almost 10 percent of LGBTQ students reported hearing homophobic comments from teachers daily or weekly. Even more LGBTQ students (15 percent) heard teachers use negative gender-related or transphobic comments daily or weekly.

- More than a third of youth with LGBTQ parents reported being verbally harassed about the sexual orientation of their parents.

- More than one in five LGBTQ students reported being physically harassed or assaulted due to their sexual orientation.

- Over a quarter of youth with LGBTQ parents reported being physically harassed about the sexual orientation of their parents.

While the Canadian findings identify high rates of homophobic and transphobic verbal and physical harassment, they also found that Safer Schools Policies can have an impact in reducing harassment.

While the Canadian findings identify high rates of homophobic and transphobic verbal and physical harassment, they also found that Safer Schools Policies can have an impact in reducing harassment.

The Role of Safer Schools Policies and PSGs

The EGALE research identified that “generic safe school policies that do not include specific measures on homophobia are not effective in improving the school climate for LGBTQ students.” In fact, “LGBTQ students from schools with anti-homophobia policies reported significantly fewer incidents of physical and verbal harassment due to their sexual orientation.

Students from schools with PSGs (both LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ) are much more likely to

- agree that their school communities are supportive of LGBTQ people;

- be open with some or all of their peers about their sexual orientation or gender identity;

- see their school climate as being less homophobic.

Supports for Ally Teachers

The Ontario Positive Space Teacher’s Association (OPSTA) is an organization committed to helping teachers “transform Ontario schools into learning environments that explicitly welcome, respect, include, support, inspire, and reflect LGBTQ students through their policies and practices.”

Started last year by five teachers from the HWDSB, this group functions mainly through an online presence (www.opsta.com). The site provides a wealth of resources available for students, parents, and teachers to help create Positive Space in their secondary schools.

Given evidence of the powerful impact of the LGBTQ Positive Space movement for LGBTQ students, students with LGBTQ parents (or other family members), and allies, it’s high time the leadership in every secondary school took on the task of ensuring PSGs are up and running. Both the research and resources are there to support this action. Then we can move on to elementary schools, where the conversation needs to start.

EN BREF – L’isolement vécu par les jeunes LGBTQ, dissimulant leur orientation sexuelle dans une partie, voire la totalité de leur vie, accroît leur taux de consommation d’alcool, de drogues et de cigarettes, ainsi que les problèmes de santé mentale et de suicide. Selon des études nationales américaines et canadiennes, les jeunes LGBTQ sont de trois à six fois plus susceptibles de se suicider que leurs pairs hétérosexuels et 30 pour cent des suicides chez les jeunes se rapportent à leur identité sexuelle. Toutefois, les élèves fréquentant des écoles où il y a des alliances entre gais et hétérosexuels disent entendre moins de remarques homophobes, subir moins d’intimidation et d’attaques liées à leur orientation sexuelle et être plus enclins à rapporter des incidents d’intimidation et d’agression au personnel scolaire. Ils ont moins tendance à éprouver de l’insécurité due à leur orientation sexuelle et s’absentent moins de l’école. Ils ressentent aussi un plus grand sentiment d’appartenance à leur milieu scolaire.

1 Deirdre Pike, Creating and Supporting LGBTQ Positive Space Groups in the Hamilton Wentworth-District School Board – A Resource Guide for Secondary School Administrators, Teachers, and Support Staff (2010), 8. www.sprc.hamilton.on.ca/reports.php)

2 A. Peterkin and C. Risdon,Caring for Lesbian and Gay People: A Clinical Guide (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003)