Reconceptualizing Teacher-Student Relationships to Foster School Success: Working Alliance Within Classroom Contexts

The environments in which children live and learn have a significant impact on their development. Since classrooms are undoubtedly one of the most influential contexts in which children participate, it is not surprising that positive teacher-student relationships have been shown to contribute to students’ overall school adjustment, including their psychosocial, behavioural, and academic functioning.[1] However, teachers often find it a challenge to develop meaningful connections with all of their students, particularly with those who demonstrate learning and/or behavioural difficulties.

Tyler is a bright and lively Grade 5 student in Ms. Rose’s homeroom class. Although he is usually easy-going, he has difficulty focusing in class and often becomes loud and disruptive during work periods. When speaking with Ms. Rose, he often complains that no one likes him or listens to what he has to say. Tyler’s performance and engagement in classroom tasks is inconsistent. He sometimes appears to understand what is expected of him, but at other times appears completely lost. He rarely asks for help and often seems confused about where he went wrong. When a difficult situation arises in the classroom, Tyler will often refuse to discuss it or consider how he may have reacted differently. Several times, he has become oppositional and had angry outbursts when confronted by Ms. Rose about his behaviour.

Ms. Rose tries hard to build a relationship with Tyler, but his inconsistent behaviour is frustrating. Most teachers have experienced a similar situation; they understand the importance of forming an emotional connection with their students, but find it challenging, especially with students who experience difficulty in the classroom due to a combination of social skills, behaviours, and inconsistent academic performance. This is of utmost concern, since a positive teacher-student relationship seems to have an ongoing protective influence, especially for children who are struggling at school.

The Challenge in Building Relationships

An emotional bond is a fairly abstract concept, so it is not surprising that emotional connections can be difficult to target and improve. Can we truly describe the concrete behaviours that enhance the quality of teacher-student interactions? How might we begin to understand ways to build relationships with our most difficult students?

While we know that strong, positive teacher-student relationships improve student engagement and the likelihood of school success, this relationship is often too narrowly defined. In fact, existing research tends to measure the quality of the relationship exclusively as the degree to which teachers perceive a liking, trust, connectedness, or a general absence of conflict between themselves and their students. This bond is clearly important, but relationships in the context of the classroom are also influenced by the interactions relating to learning goals and tasks.

Vanessa is a student in Ms. Steacy’s Grade 3 class. She gets along well with teachers, school staff, and her classmates. Vanessa has recently been identified as having a reading disability, and she is finding it very difficult to keep up with classwork and assignments. Although Vanessa is a very agreeable student, she will often leave her work unfinished. Ms. Steacy believes that she has a strong bond with Vanessa, but senses that Vanessa does not feel like a contributing and productive member of the classroom. She wants Vanessa to feel comfortable asking questions and coming to her for extra help. At times, Vanessa seems unaware of what is expected of her and does not believe that her reading difficulties will improve. This impacts Vanessa’s perceptions of herself and her abilities, as well as her willingness to take risks in her learning. She often finds the reading demands overwhelming and will give up when confronted with tasks that she thinks are “too hard”. During conversations with Ms. Steacy, Vanessa becomes negative about her progress and questions the point of doing the work when she can’t read.

Because the classroom should be an environment that fosters strong and positive working relationships, it is necessary to recognize the complexity of the interactions that take place within this context.

Ms. Steacy has a positive emotional connection with her student. Vanessa likes and respects her teacher and enjoys working in her classroom. But she does not feel secure in trusting her teacher with her learning needs – likely due to her past experiences with failure in reading. In this example, we can see the limitations in understanding the teacher-student relationship as primarily an emotional connection. This restrictive definition can make it difficult to teach concrete skills that enhance the quality of interactions, to focus on students’ needs related to the tasks of learning, and to surpass personality differences that may exist between teachers and students. Because the classroom should be an environment that fosters strong and positive working relationships, it is necessary to recognize the complexity of the interactions that take place within this context.

Broadening the Definition of Relationship

In the counselling psychology field, this working relationship is defined as the “working alliance”, referring to the quality of the relationship between therapist and client. The quality of alliance has consistently been found to be one of the best predictors of positive outcomes for clients participating in therapy. The construct of the working alliance is comprised of three components: bond, goal, and task.[2] The aspect of bond represents the emotional component of the relationship, based on mutual trust, respect, and caring. However, alliance also encompasses the aspects of relationship that focus on building a sense of partnership; this includes the shared development and understanding of the established goals and the tasks that need to be undertaken to achieve those goals.

In order to expand the investigation of working alliance to the classroom setting, my colleagues and I developed the Classroom Working Alliance Inventory (CWAI)[3] – a questionnaire that considers both teachers’ and students’ perceptions, and broadens previous definitions to consider variables unique to a classroom working relationship. This inventory replicates the three critical components of alliance: bond, goal, and task. The Bond questions ask teachers and students about their general feelings toward one another (e.g., “I believe Tyler likes me” and “My teacher and I trust one another”).

While this first component taps the emotional aspects of relationship, the remaining components focus on the collaborative aspects that characterize a working relationship. The Goal questions measure the extent to which the teacher and student feel that they are collaborating on the classroom goals by tapping their mutual understanding about classroom objectives (e.g., “We are working towards goals that we have agreed upon together” and “We agree about what I need to do differently in school”). The Task questions ask whether teachers and students feel that assigned tasks are relevant to each individual student’s learning and will help him or her achieve success (e.g., “I am confident that what Vanessa is doing in school will help her learn better in the areas that she has difficulty” and “My teacher and I agree about the things I need to do to help me improve my schoolwork”).

In our recent work, the CWAI was completed by 430 Grade 3 students and their teachers and was found to be an internally consistent and externally valid measure of teacher-student relationship, supporting its use in research.[4]

Investigation of the Working Alliance Within Classrooms

Over the past several years, we have begun to investigate how teacher-student alliance is related to perceptions of school performance, school satisfaction, and various other school-related outcomes. The first study to employ the CWAI examined elementary students’ and their teachers’ reports of alliance, and how these reports related to perceptions of students’ school performance. We found that students who felt that they had a strong working alliance were more likely to engage in positive learning behaviours, as rated by both themselves and their teachers. Teachers’ ratings of alliance, on the other hand, predicted only their own views of student performance, and not the students’ perceptions of their own engagement. These findings indicated to us that student evaluations can provide important information about the quality of classroom working alliance, a notion that has previously been overlooked in much of the teacher-student relationship literature based solely on teacher reports.[5]

In a further study, we found that both teacher and student ratings of working alliance were related to elementary students’ reports of school satisfaction. Not surprisingly, students who felt that they had strong, positive working alliances with their teachers were more likely to enjoy and have positive attitudes toward school, engage in classroom activities, and express affiliation with their schools.[6]

In one of our most recent studies, we were interested in examining classroom working alliance among upper-elementary students with and without special needs (identified learning and/or behavioural difficulties). We found that teachers generally had more negative perceptions of their alliance with students with special needs, whereas, students with and without difficulties showed no difference in their own perceptions of alliance.

In this study, ratings of alliance were found to influence a number of school-related outcomes for all students. However, when examining academic competence and school satisfaction, it appeared that the collaborative elements of working alliance (goal/task) were particularly important for students with special needs. That is to say, students with special needs who felt that they had a positive and collaborative alliance with their teachers were less likely to express levels of low academic competence and school satisfaction.[7]

Putting Classroom Working Alliance Into Practice

Understanding alliance. It is clear that the quality of teacher-student relationships can contribute to a classroom atmosphere that fosters student success. However, until recently, we had yet to explore the construct of working alliance within an educational context. The research conducted to date offers strong evidence that positive teacher-student working alliance is related to students’ overall school adjustment. Although students with special needs appear to have more strained relationships with their teachers, there is an indication that the collaborative aspect of alliance can play a protective role for these students and compensate for other factors that place them at risk for school difficulties. As this reconceptualization of teacher-student relationship encompasses not only emotional connections (bond), but also collaboration (goal/task), it is helpful for teachers to understand that each of these elements holds equal weight. We want to connect with our students on an emotional level, as well as recognize our partnership surrounding the work of schools and classrooms.

As this reconceptualization of teacher-student relationship encompasses not only emotional connections (bond), but also collaboration (goal/task), it is helpful for teachers to understand that each of these elements holds equal weight.

School-based interventions. When a student is experiencing difficulties at school, our interventions rarely focus on enhancing relationships. Our research has suggested that students’ perceptions of alliance are associated with various school-related outcomes and that we should consider how students are feeling about the working relationships they have with their teachers. This is particularly important during the early elementary years when students who have difficulties with the school environment may benefit from interventions to foster their affiliations with teachers in the classroom before their adjustment is threatened. This could be accomplished by meaningfully involving students in a collaborative effort to promote understanding and agreement of classroom goals, rules, structures, and activities. Teachers can also seek students’ input about their own strengths and needs, while aligning the tasks of the classroom or their resource support with the difficulties that students acknowledge.

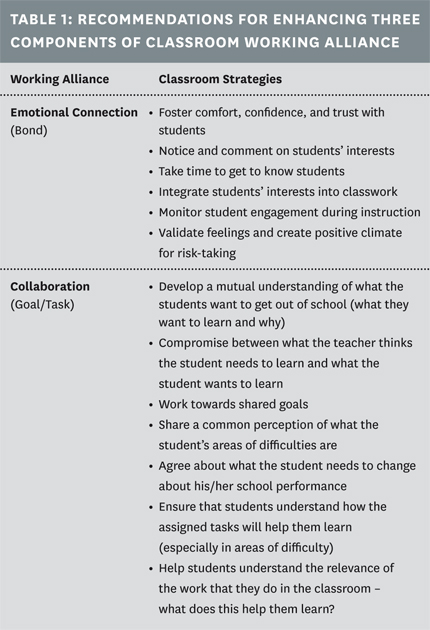

Alliance-building. It is not surprising that the relational aspects of the classroom are often overlooked in teacher education. Using our previously limited understanding of relationship, it can be difficult to provide teachers with concrete guidelines and tools for developing emotional connections with each of their students. How can you learn to “like” someone? Some teachers are less skilled or comfortable with developing emotional bonds with their students, and some students can certainly pose a challenge in trying to establish these connections. The construct of working alliance provides another way for teachers to develop meaningful relationships with their students, through collaboratively setting goals and clearly linking classroom tasks to those goals. Table 1 provides some simple suggestions to get us started in the task of developing guidelines for alliance-building within the classroom.

Conclusion

Teacher-student relationship has previously been shown to be a powerful predictor of students’ classroom and school adjustment. Beyond the characteristics of warmth, trust, and bond that define an emotional connection, a positive working relationship also includes a sense of collaboration and partnership shared between the teacher and the student.

EN BREF – Il a été démontré que la relation maître-élève est un prédicteur déterminant de la capacité d’adaptation de l’élève à sa classe et à son école. Au-delà des caractéristiques relatives à un climat chaleureux, à la confiance et à l’engagement qui définissent un lien affectif, une relation de travail positive comprend également des valeurs partagées de coopération et de partenariat entre l’enseignant et l’élève. Le questionnaire CWAI (Classroom Working Alliance Inventory- Inventaire des relations de travail en classe) tient compte des perceptions des enseignants et des élèves et donne un sens élargi aux définitions antérieures caractérisant les variables propres à la relation de travail en classe. Cet inventaire reprend les trois composantes critiques d’une relation de travail réussie : engagement, but et tâche. Des études indiquent que des élèves ayant le sentiment de profiter d’une solide relation de travail sont plus susceptibles d’avoir des comportements d’apprentissage positifs, selon leur propre évaluation et celle de leurs enseignants.

Thank you to my colleagues who have contributed to this program of research: Dr. Nancy Heath, Department of Educational & Counselling Psychology, McGill University and Dr. Elana Bloom, Lester B. Pearson School Board, Montreal, QC.

[1] R. C. Pianta, Enhancing Relationships Between Children and Teachers, (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1999).

[2] A. O. Horvath and R. P. Bedi, “The Alliance,” in Psychotherapy Relationships That Work: Therapist Contributions and Responsiveness to Patients, J. C. Norcross, ed. (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2002).

[3] N. L. Heath, J. R. Toste, L. Dallaire, and M. Fitzpatrick, Classroom Working Alliance Inventory (McGill University, 2007).

[4] J. R. Toste, N. L. Heath, and C. M. Connor, The Construct Validity of the Classroom Working Alliance Inventory (CWAI). Manuscript in final preparation.

[5] J. R. Toste, N. L. Heath, and L. Dallaire, “Perceptions of Classroom Working Alliance and Student Performance,” Alberta Journal of Educational Research 56 (2010): 371-387. Retrieved from http://ajer.synergiesprairies.ca/

[6] J. R. Toste and N. L. Heath, Fostering Resilient Classrooms: Exploring the Relationship Between School Satisfaction and Teacher-student Alliance. Manuscript in final preparation.

[7] J. R. Toste, E. L. Bloom, and N. L. Heath, Differential Role of Classroom Working Alliance in Predicting School-related Outcomes for Students With and Without Special Needs. Manuscript in final preparation