Journeys in Youth Mental Health

Complex young lives in a fractured system

Young people with mental health challenges are among our most vulnerable students in Canada. They are also among our most interesting and courageous. Their lives can be difficult and are too often stigmatized, even though so many are working hard to change this. Many of these young people are navigating a sea of additional troubles such as poverty, loneliness, marginalization, fear and frustration that lead to the spirals of decline[1] and cultures of silence[2] that they have so eloquently detailed for us.

We know a lot about the alarming trends in mental illness in the lives of modern Canadian youth. The Canadian Mental Health Association[3] now estimates that 10-20 percent of Canadian youth are affected by a mental illness, with 3.2 million (12-19 years) at risk for developing depression. Others estimate that 30 percent of students suffer from psychological distress[4] with only a minority (1 in 5) receiving formal supports, which suggests why Canada’s youth suicide rate is now the third highest in the industrial world.[5] We also know that the growth in social inequality and poverty are closely related to mental health for youth.[6] In fact, youth from impoverished backgrounds are three times more likely than their wealthier peers to experience mental health challenges. The most pressing factors in poor mental health include poverty, learning difficulties, abuse/neglect, isolation, lack of support, and lack of access to quality health care and education.[7] However, we know far less about the journeys that these young people are taking toward better mental health.

Journeys: knowing young lives

I knew that it wasn’t just being depressed for a few days, but for a long period of time being depressed… everyone says that getting help is easy, but it really isn’t, like when you get help, you have to wait so many months to actually get the help. So I just feel like nobody does anything for those few months while you’re waiting, and that’s what people really need to do.

And when I went to my cousin, because I could trust her, and tell her I was depressed, she said, ‘What do you have to be depressed about?’ and that’s so depressing, because it’s like, do you not realize that being 16 is hard?

Few researchers and educators have yet had the opportunity to focus on the journeys and experiences of these remarkable young people. Most research illustrates the important, if paradoxical, processes of diagnosis and treatment. But too few young people receive either, and diagnoses can also lead to labeling and further stigmatization. Moreover, what awaits too many kids and families is a heartbreaking experience with a youth mental health system that is fractured and ruptured.

Where have these kids been and where are they going? As educators and parents, this is our shared concern. How do we best assist in the life journeys of these young people? Mapping the journeys of young people into and out of mental health care is one good way of seeing the complexity of these young lives and the best ways to help. Journey mapping is a newer approach to research that gathers stories from youth relating to their experiences and provides visual maps of how they have navigated the system. This strategy is now used by international researchers to identify barriers and facilitators in access and care for mental health.

Our systematic review of this international research literature on journeys in youth mental health yielded 25 recently published English-language journal articles from Canada, Italy, Eastern Europe, New Zealand, the U.S., the U.K., India and China. Three themes arose in our synthesis of this literature:

1. youth journeys in mental health are non-linear in character;

2. barriers and facilitators exist at personal and systemic levels and often in paradoxical fashion; and

3. schools and teachers are crucial in this journey.

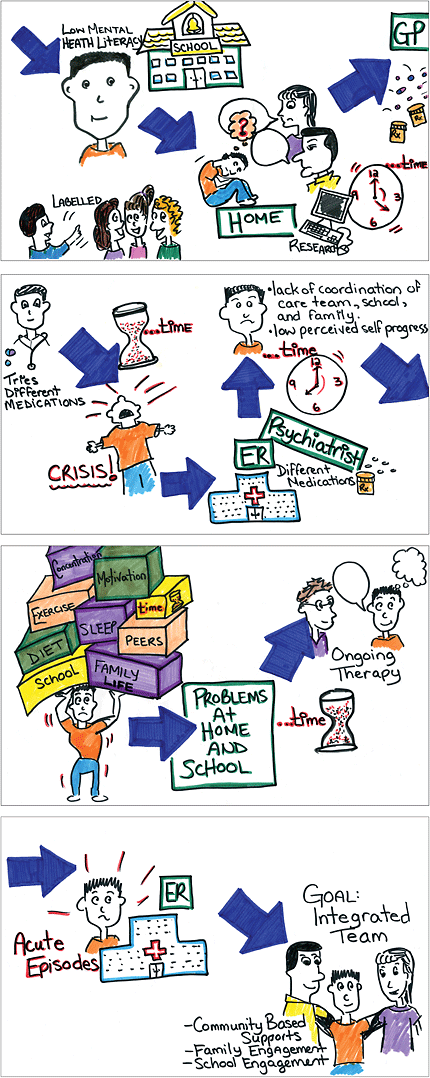

Young people take individualized and dynamic journeys to seeking mental health supports.[8] These journeys often start long before they receive formal care from a primary health care provider and with their own early experiences and interactions at home and in school.[9] The non-linear character of these journeys shows us where we could best intervene in a too-often fractured system. We can see in the visual maps how the elements of the system become tied together in a back-and-forth motion as youth and families move in and out of primary health care, school supports, acute health care, and so forth. The recent work in patient journey mapping from Kamloops, B.C.[10] offers an excellent illustration of the journey, with long-term wait times and breaks in the continuity of care. We have further developed this model to assemble a journey map that represents lessons and themes found in our review of literature (see illustrations 1 to 4).

Our image shows the paradoxical journey model that we have detected and demonstrates how personal relationships and systemic structures encountered by youth can exacerbate or alleviate problems that accompany mental health challenges. For example, while there is a shortage of skilled mental health professionals in some areas, most work very hard on a daily basis to go above and beyond their job descriptions in providing excellent care despite the heavy loads. Another example of the paradox is that while poverty stretches the resources and time of these families, many parents are going to extraordinary lengths to advocate for their children in the face of great adversity. Thus, mirror-image supports exist for each barrier, as evidenced in a surprising range of facilitators from which we must launch meaningful change for these young people. Teachers, parents, friends and mental health professionals could form a core community of helpers.

Notably, young people also identify their schools as significant in their journey. In some cases, the school is not seen as a safe or supportive place to be and/or to seek advice or information. School peers are identified as “silent actors” in the journey, with a role that remains both unclear and complex. The role of school peers in inciting stigmatization is clear; however there are also signs of school peers acting in supportive and assistive roles. There is a need for schools to do better in providing these safe spaces for knowledge about mental health.[11]

“Taking mental health to school”

With the complexity and nonlinearity of the youth journeys in mental health, we must ask if and how the school can best provide a reasonable space for prevention and assistance. When youth arrive at school each day, they enter the halls and classrooms with the lives they are immersed in. These lives collide with the range of human and structural relationships that make up the everyday spaces of school. We know that these students are asking for early and local access to mental health supports, a place where they belong without stigma, and a school environment that will both increase mental health awareness and decrease stigma.

An important Canadian study was recently released from the Centre of Excellence of Child and Youth Mental Health in Ontario in which the authors provide an overview of the best ways we can “take mental health to school.” The evidence shows how schools are both necessary and helpful in addressing youth mental health. Not surprisingly, the report finds that “student mental health needs exceed the current capacity of school systems to respond adequately. Education leaders are looking for: leadership and coordination, professional development, and guidance in selecting programs and models of cross-sectoral service delivery…”[12] Programs found to be of use in schools relate to stress or anger management, reducing violence and substance abuse, and modifying the school environment to promote self-awareness and positive relationships. School boards were directed to implement such programs with fidelity and in collaboration with local mental health agencies and parents.

In our recent project on mental health in schools, the investigative team from the Hospital for Sick Children and University of Prince Edward Island took the pulse of students and educators regarding mental health literacy.[13] Working with a mural created by eight young people who experienced mental illness, we installed their original image in six secondary schools in Ontario and four in P.E.I., to invoke a conversation about mental health literacy (see photo on page 4). The image has now been viewed by approximately 7,000 students and teachers in Canada who have shared with us a meaningful conversation about mental health and stigma. The installation of the mural was somewhat different in each school, with many young people and teachers assisting us in finding a prominent place for it to hang and acting as ambassadors for the mural during the two weeks of installation in each school. The installation was followed by a large group “talk back” session in the form of an assembly in which the Canadian Mental Health Association joined us in leading a session about the mural and about youth mental health. This was followed by focus group conversations with students and educators (separately) and by analysis of the writings and comments they provided on large sheets of paper and comment cards left for this purpose.

Early analysis of the data from P.E.I. schools suggests that the majority of students and educators were grateful for the opportunity to have a mental health conversation. To many, it seemed long overdue. They also commended the young artists for their demonstration of great courage in sharing their mental health journeys in artistic form. In fact, some of these schools have now taken on similar art-inspired projects with their own students for Mental Health Awareness Week. The students appreciated the use of art in depicting the complex experiences of young people in mental health, as they felt that it allows for deeper understanding and interpretation of the experiences they are facing. Many students also expressed that the mural and conversation in the school provided reassurance that they were not alone in their mental health experiences. They reported a clear desire to learn more about youth mental health and illness. Students wanted the opportunity to have further discussions, learn about the clinical aspects of mental health and illness, and better understand what services are available to them in school and community. They expressed a strong need to better address and eliminate stigma in their schools and communities.

I think the mural spoke of issues that people struggle with. I think the best ways to get knowledge are by having small meetings and discussing it to give everyone the chance to speak in a small group. I think art is a beautiful and approachable way to discuss and get knowledge on mental health. – student

The thing for me is that, I am not trained in that [mental health support]. We are talking about kids, but let’s face it, there are teachers and adults in the community who have all these issues… And my curriculum doesn’t really allow for a broad conversation, right? So I see the mural as a stimulator of mental health discussion and it shows the point of having the conversation, and how we keep that going.” – educator

Our review of the literature and our interviews with students and teachers in the mural project uphold important messages about youth journeys in mental health. We contend that Canada is moving along a good path in addressing the alarming trends in youth mental health. We offer youth journeys as a tremendous jumping-off point in examining the complexity of these young lives and in pointing to promising ways to support them. There is need to better coordinate services, reduce wait times, meaningfully address stigma and open up new spaces for families, schools, and mental health professionals to assist youth in their journeys to mental health. Their experiences call us to action in breaking the spirals of decline and cultures of silence that society has left them to negotiate.

Next Steps

We are pleased to announce ACCESS-MH,[14] a five-year project in Atlantic Canada, funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Our study applies youth mental health journeys with related statistical information from Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Building upon the knowledge and methods now emerging in youth mental health journeys, this project includes conversations with parents, teachers, primary health care providers, and community members. We also invoke arts-based methods of understanding experiences and mapping journeys. The variety of participants will further identify complex problems youth face in seeking mental health care. Our work aims to better assist in the creation of a more coherent network of support and programming for our vulnerable and courageous Canadian youth.

Photo: Katherine Boydell

First published in Education Canada, March 2014

EN BREF – La santé mentale des jeunes est une préoccupation de taille de la société et des écoles canadiennes. En fait, il s’agit d’une question dont on parle de plus en plus dans le monde entier. Ce texte présente une nouvelle façon prometteuse de comprendre le problème en plaçant les parcours de vie des jeunes au centre de notre attention. Nous ouvrons ainsi de nouveaux espaces où les écoles peuvent collaborer avec des partenaires de la collectivité et du domaine médical de la santé mentale pour constituer un système plus cohérent destiné à entourer la vie complexe et courageuse de nos élèves.

[1] K. Tilleczek and V. Campbell, “Barriers to Youth Literacy: Sociological and Canadian insights,” Language and Literacy 15, no. 2 (2013): 77-100.

[2] S. Kutcher and A. McLuckie, Evergreen: A child and youth mental health framework for Canada, for the Child and Youth Advisory Committee, Mental Health Commission of Canada (Calgary: 2010).

[3] Canadian Mental Health Association, Fast Facts About Mental Illness. www.cmha.ca/media/fast-facts-about-mental-illness/#.Us1uj7SmYk8

[4] A. Paglia-Boak, R. E. Mann, E. M. Adlaf, J. H. Beitchman, D. Wolfe, and J. Rehm, The Mental Health and Well-being of Ontario Students 1991–2009: Detailed OSDUHS findings (Toronto: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, 2010).

[5] E. J. Costello, H. Egger, and A. Angold, “10-year Research Update Review: The epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: Methods and public health burden,” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 44, no. 10 (2005): 972–986; CMHA, Fast Facts, www.cmha.ca/media/fast-facts-about-mental-illness/#.Us1uj7SmYk8

[6] For a current review of literature linking social inequality, poverty and mental health see Tilleczek, Ferguson, Campbell and Lezeu (in press), “Mental Health and Poverty in Young Lives: Intersections and directions,” Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health.

[7] E. L. Lipman and M. Boyle, Linking Poverty and Mental Health: A lifespan view (Ottawa: The Provincial Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health at CHEO, 2008).

[8] K. Boydell, R. Pong, T. Volpe, K. Tilleczek, E. Wilson, and S. Lemieux, “Family Perspectives on Pathways to Mental Health Care for Children and Youth in Rural Communities,” Journal of Rural Health 21, no. 2 (2006): 182-188.

[9] S. De la Rie, G. Noordendos, M. Donker, and E. van Furth, “Evaluating the Treatment of Eating Disorders from the Patient’s Perspectives,” International Journal of Eating Disorders 39, no. 8 (2006): 667-676.

[10] S. Scott, S. Sze, K. Weatherman, and R. Gorospe, “Kamloops Patient Journey Mapping Report, Child and Youth Mental Health” (unpublished manuscript, 2013).

[11] K. M. Boydell, T. Volpe, B. M. Gladstone, E. Stasiulis, and J. Addington, “Youth at Ultra High Risk for Psychosis: Using the Revised Network Episode Model to examine pathways to mental health care,” Early Intervention In Psychiatry 7, no. 2 (2013): 170-186.

[12] D. Santor, K. Short, and B. Ferguson, Taking Mental Health to School: A policy-oriented paper on school-based mental health for Ontario (Ottawa: The Provincial Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health at CHEO, 2009), 6.

[13] K. Boydell, “Using Visual Arts to Enhance Mental Health Literacy in Schools,” in Youth, Education and Marginality: Local and global expressions, eds. K. Tilleczek and B. Ferguson (Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2013).

[14] Atlantic Canada Children’s Effective Service Strategies in Mental Health is a CIHR-funded project lead by Dr. Rick Audus (MUN), Dr. Kate Tilleczek (UPEI), Dr. Scott Ronis (UNB) and Dr. Micheal Zhang (SMU).