Teen Stress in Our Schools

A 45-minute program to improve coping skills

For the average high school student, life is full of potential stressors. In a recent survey, our research team asked over 900 Grade 7 students what they identified as the biggest stressors in their lives. “Academic difficulties” was reported as the greatest stressor by 33.2 percent of students, followed by “conflict with parents/family” (31.4 percent), “conflict with peers” (20.7 percent), and “conflict between parents” (13.9 percent). Of particular concern is how these students are coping with their stress.[1]

For the average high school student, life is full of potential stressors. In a recent survey, our research team asked over 900 Grade 7 students what they identified as the biggest stressors in their lives. “Academic difficulties” was reported as the greatest stressor by 33.2 percent of students, followed by “conflict with parents/family” (31.4 percent), “conflict with peers” (20.7 percent), and “conflict between parents” (13.9 percent). Of particular concern is how these students are coping with their stress.[1]

Research on stress and coping has found that adaptive coping strategies (e.g. support seeking, problem solving) develop in early childhood and taper off in early adolescence.[2] We asked the participating Grade 7 students how they cope with the stressors in their lives. While adaptive coping strategies were reported (e.g. “listen to music,” “play sports,” “talk to someone”), students also reported an alarming use of maladaptive coping strategies to manage stress. Seven percent of students indicated engaging in “risky behaviours” such as drug/alcohol use and unprotected sex to manage stress. Another concerning behaviour reported by students was “hurting self on purpose” – 7.3 percent of students indicated using methods such as cutting, burning or scratching the skin to manage stress. A slightly smaller percentage of students (5.8 percent) reported “problematic (excessive) video game use.”

Adolescent stress is often a risk factor for poor mental health outcomes such as anxiety and depression; however, there is evidence that the ability to effectively manage stress is strongly related to psychological adjustment.[3] Consistent with previous research, our findings shed light on the emergence of coping difficulties as early as Grade 7, which makes the teaching of adaptive coping skills in early adolescence an integral part of building resilience in students.

The school represents an ideal setting to conduct a universal adolescent mental health program to promote adaptive coping strategies. A universal treatment approach includes all individuals in a target population. This approach may minimize difficulty with screening and recruitment, and prevent problems such as low participation and retention rates.[4] Furthermore, universal mental health programs serve to decrease stigma and increase peer support.[5] Despite their benefits, universal mental health programs are often met with resistance due to concerns related to curriculum interference and the added cost of training. Clinic-based treatment programs have been adapted to the high school setting;[6] however, these school-based programs typically run from six to ten weeks, which is challenging to implement within most school curricula.

The StressOFF Strategies program

In response to these challenges, our research team developed StressOFF Strategies: A Stress Management Program for Teens, a single-session 45-minute program that has been delivered to over 2,000 high school students and received very positive evaluations from both students and school personnel. Given the brevity of the program, we had to be very judicious in the selection of program content to maximize program effects. After a comprehensive review of existing empirically supported stress management programs for adolescents, we designed and then piloted a program to a group of teens. Findings from the review were synthesized with teen recommendations, which led to the identification of four key components ofStressOFF Strategies program content:

- Psychoeducation;

- Decreasing stigma;

- Coping skills; and

- Follow-up (pamphlet and online activities).

Psychoeducation

In the psychoeducation component of the program, students are provided with a developmentally appropriate definition of stress – with a focus on adaptive versus maladaptive stress – followed by the cognitive, physiological and behavioural signs of stress. Students then fill out a brief questionnaire, which gives them an idea of their own stress level (mildly stressed, moderately stressed, or highly stressed). Students are also encouraged to fill out “My Personal Stress Profile,” a brief checklist of the cognitive, physiological, and behavioural signs of stress that they may have experienced. This profile provides students with a way of understanding if their stress generally expresses itself more cognitively, physically, or behaviourally, in order to tailor their coping responses accordingly (which are addressed in the second half of the program).

Decreasing stigma

Though we have made many strides as a society, stigma around mental health issues persists. By making the program universal, we hope to suggest that stress is a common experience, shared by all at one point or another. Following the students’ recommendations, we begin and end the program with a video of Scott, an attractive, successful, university undergraduate student who struggled with stress in high school. In the video, Scott speaks directly to the students, reassuring them that they are not alone in their stress, and that there are strategies to help manage stress, which they will learn throughout the program.

To further strengthen our message that stress is universal, we introduce three images of current, well-known celebrities who have spoken publicly about their struggles with stress, followed by a “Celebrity Stress Trivia” game in which students are provided with scenarios illustrating these popular celebrities’ real struggles with stress, and asked to guess which celebrity corresponds to the given scenario.

Coping skills

An integral part of the program is teaching coping strategies to students. The coping strategies selected for this program are drawn from cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). CBT is a therapeutic approach that emphasizes the idea that our thoughts, or the way we perceive an event or situation, influence the way we feel and behave. Therefore, an important part of CBT is learning how to identify and correct distorted thinking through a process called cognitive restructuring.[7] CBT also incorporates relaxation exercises to help reduce physiological arousal, which can interfere with one’s thinking and handling of difficult situations, and teaches behavioural strategies to help individuals become aware of and modify unhealthy ways of behaving.

Mindfulness refers to being aware of present-moment thoughts and feelings without judging them; rather it entails accepting both positive and negative thoughts and feelings, as they are experienced.[8] While CBT uses cognitive restructuring to engage with negative thinking, mindfulness encourages cognitive defusion, a strategy that helps individuals gain some distance from negative thoughts and feelings and recognize them for what they are – little bits and pieces of language or sensations. By paying attention to thoughts and feelings in this way, mindfulness helps individuals recognize and manage difficult emotions without becoming overwhelmed by them, and provides a way of coming back into the present when these emotions arise.

The strategies from CBT and mindfulness that were selected for the program target the cognitive, physiological, and behavioural signs of stress. Together they form the acronym STRESS – for Stop, Thought challenge, RElaxation, Self-observer, Support and better choices – which can make it easier to recall and access the strategies.

Cognitive strategies: Stop and Thought challenge

With this strategy, we first present students with a negative thought, such as “I’m a complete failure!” We ask them to stop and take a deep breath. We then tell students to challenge the thought by asking: If a friend came up to me and articulated this same thought, would I say, “Yeah, you’re a failure?” Most of the students understand that they would not speak like this to a friend who is upset. Hence, the message we are trying to drive home is, if you wouldn’t say this to a friend, why would you say this to yourself?

“I think that the program was presented at the right time because I was more stressed. I think every school should have this program.” – 15-year-old female student

Physiological strategy: Relaxation

While relaxation can mean different things to different people (some listen to music, others like to take a walk), students may begin to feel stressed in a situation in which they cannot turn to their usual ways of relaxation. One strategy that can be used anywhere and at any time is muscle relaxation. Muscle relaxation reduces physiological stress by progressively tensing and then relaxing each muscle group in the body. Students are guided through a step-by-step muscle relaxation exercise while sitting at their desks.

Cognitive/physiological/behavioral strategy: Self-observer

Through the self-observer mindfulness strategy, students are taught how to become aware of the present moment without judging; just “observing.” As with the muscle relaxation strategy, the self-observer strategy can be used at any time and any place, particularly when experiencing overwhelming thoughts and feelings. Students are guided through “The Chair” exercise, a step-by-step self-observer activity which helps students turn attention away from negative thoughts and feelings by focusing on their senses (e.g. the feeling of the chair, the sounds that come to their ears), and finally turning their observation to their breath, without trying to change or alter anything.

“I am a stressed person and for a very long time I was looking for a way to help my stress problem. With this presentation, I really think my life will be better.” – 15-year-old female student

Behavioural strategy: Support and better choices

Students are encouraged to reflect on the choices they make when feeling stressed, and on whether their behaviours may induce further stress. While having the right tools can be helpful in managing stress, students are also made aware of how simple lifestyle choices, such as eating well, getting enough sleep, and exercising routinely can also reduce stress. Furthermore, students are encouraged to access their support network or to seek help when experiencing difficulty coping.

Follow up

Following the program, students are given a pamphlet that outlines the information provided in the workshop, including the four strategies. Finally, students are directed to the StressOFF Strategies webpage, where students can find program resources and access links to other helpful stress management resources.

Program evaluation

To facilitate delivery and ensure treatment fidelity, we created a detailed script to guide animators through each PowerPoint slide and related activities. The program animators, all university students, were required to learn the script by heart.

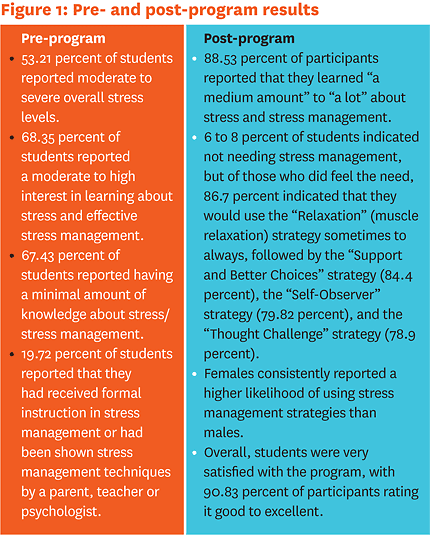

To evaluate the effectiveness of the program, we collected data from 218 Grade 9 students (aged 14 to 16; 56 percent female, 44 percent male) from classes in two large public secondary schools in Montreal, Quebec. Students filled out questionnaires immediately before and after the 45-minute stress management program. The questionnaires addressed our two research objectives: (1) To report on students’ pre-program stress, knowledge of stress and previous stress management instruction; and (2) to evaluate the stress management program by examining participants’ post-program reports of knowledge of stress and stress management and willingness to use stress management techniques, as well as their overall satisfaction with the program. (See Figure 1 for pre- and post-program results.)

Overall, results from the evaluation study of StressOFF Strategies provide encouraging support for the implementation of a single-session, school-based universal stress management program. Although preliminary, our findings demonstrate that a brief stress management intervention can increase students’ knowledge of stress and stress management, and impact their willingness to use stress management strategies in the future.

High school students report moderate to high levels of stress as a result of academic, social, and family difficulties; yet the majority of these students do not know how to effectively manage their stress. However, they are interested in learning about stress management and are willing to use effective stress management strategies once taught. With the increasing emergence of maladaptive coping behaviours at an earlier age, the teaching of effective stress management plays an important role in averting the potentially lifelong consequences of maladaptive coping and chronic stress. Our study has demonstrated that stress management instruction does not have to span several weeks in order to be effective. A brief intervention can increase students’ knowledge of stress and stress management, and open the door to effective strategy use in the long term.

“I have now learned I’m not alone with stress and a lot of people feel the same way.” – 14-year-old male student

Illustration: iStock

First published in Education Canada, March 2014

EN BREF – Les élèves du secondaire indiquent ressentir de plus en plus de stress causé par des difficultés scolaires, sociales et familiales, sans savoir très bien comment le gérer. Par conséquent, un nombre inquiétant de jeunes y font face en adoptant des comportements mésadaptés comme la prise de risques, l’automutilation non suicidaire et l’utilisation problématique de jeux vidéo. Bien que le cadre scolaire soit un lieu idéal pour enseigner comment gérer efficacement le stress, les programmes actuels sont souvent longs, ce qui complique leur utilisation dans la plupart des programmes pédagogiques. Notre équipe de recherche a donc élaboré un programme court – d’une seule séance – portant sur les principaux éléments de la gestion du stress par les adolescents (psychoéducation, réduction de la stigmatisation et habiletés d’adaptation) et pouvant être livré en une seule période de classe. Les jeunes qui y ont participé l’ont évalué très favorablement.

[1] Amy J. Shapiro, E. Roberts, M. E. De Riggi, and N. Heath, “Effective Stress Management Instruction for Teens: What teachers should know” (presentation, Quebec Provincial Association of Teachers Annual Convention, Montreal, QC: November 22, 2013).

[2] Petra Hampel and Franz Petermann, “Age and Gender Effects on Coping in Children and Adolescents,” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 34, no. 2 (2005): 73–83.

[3] Bruce E. Compas, J. K. Connor-Smith, H. Saltzman, A. H. Thomsen, and M. E. Wadsworth, “Coping with Stress during Childhood and Adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research,” Psychological Bulletin 127, no. 1 (2001): 87–127.

[4] Sally Lock and Paula M. Barrett, “A Longitudinal Study of Developmental Differences in Universal Preventive Intervention for Child Anxiety,”Behavior Change 20, no. 4 (2003): 183–199; I. M. Shochet, M. R. Dadds, D. Holland, K. Whitefield, P. H. Harnett, and S. M. Osgarby, “The Efficacy of a Universal School-Based Program to Prevent Adolescent Depression,” Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 30, no. 3 (2001): 303–315.

[5] Carl F. Weems, B. G. Scott, L. K. Taylor, M. F. Cannon, D. M. Romano, A. M. Perry, and V. Triplett, “Test Anxiety Prevention and Intervention Programs in Schools: Program development and rationale,” School Mental Health 2, no. 2 (2010): 62–71.

[6] Diane de Anda, “The Evaluation of a Stress Management Program for Middle School Adolescents,” Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal15, no. 1 (1998): 73–85; Erica Frydenberg, R. Lewis, K. Bugalski, A. Cotta, C. McCarthy, and N. Luscombe-Smith, “Prevention is Better than Cure: Coping skills training for adolescents at school,” Educational Psychology in Practice 20, no. 2 (2004): 117–134; Petra Hampel, Manuela Meier, and Ursula Kümmel, “School-based Stress Management Training for Adolescents: Longitudinal results from an experimental study,” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 37, no. 8 (2008): 1009–1024.

[7] Aaron T. Beck, Gary Emery, and Ruth L. Greenberg, Anxiety Disorders and Phobias: A cognitive perspective (New York: Basic Books, 1985).

[8] Steven C. Hayes, “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Relational Frame Theory, and the Third Wave of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies,”Behavior Therapy 35, no. 4 (2004): 639–665; Jon Kabat-Zinn, Full Catastrophe Living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness (N.Y.: Delacourt, 1990).