What’s in a Name?

Fostering a sense of community through the wonder of names

What happens when students research the roots, meaning and stories behind their own names? Identity is at the heart of the names inquiry, encouraging students to tackle the existential questions “Who am I?” “Who are they?” and “Who are we?”

It was a cold March morning. Desks began to shuffle as 28 Grade 5 and 6 students gradually entered the classroom. Standing at the front of the room, I heard a soft whisper: “Who is she?”

“Shh! Quiet, I want to find out who she is,” responded another student.

Silence suddenly filled the room. Twenty-eight sets of eyes now stared at me, anticipating an elaborate introduction, begging me to disclose some much-needed and expected information: my name. This is the moment I had been waiting for, the moment when I was going to try something highly unusual.

“Welcome to Social Studies! I would like to begin with a story and the request that you do not tell anyone your name for the next three days.” Noticing that every student seemed to be nodding in agreement, I flicked off the main light, turned on a small lamp and began reading the story I had so carefully selected.

One by one the students became immersed in the story of two parents struggling to bestow a name upon their child. Once the story was finished, a student near the front of the classroom asked, “What do you think the world would look like without names?”

Intrigued by his question, I encouraged him to start exploring possible answers. Slowly, other students began contributing to the conversation, posing questions and brainstorming possible answers. A classroom once quiet was now an animated commons inviting all students to engage in the discussion.

“Can I be a Canadian citizen without a name?”

“What would happen if we were all named the same thing?”

“Why do we need different names?”

“If I didn’t have a name then there would be no point in being a good person, because no one would know who I was,” stated a Grade 5 student with tear-filled eyes.

Immediately struck by the depth of her observation, I pondered her statement. Although it seemed simple, it revealed something deeper: the desire every human being has to be known and to know others, to feel valued as an individual, to belong.

The wonder of names

The verb wonder can be thought of in two ways: the first is to experience curiosity or doubt – often expressed as the phrase, “I wonder what would happen if…” The second is to be fixated or fascinated with or by something.1 Wonder can also be a noun, which is the emotion of amazement and admiration provoked by an encounter with a person, place or thing. In the coming weeks, the ordinary topic of names began filling the classroom with wonder as students embraced it as their topic of study. Students talked with family members, learning more about their heritage, and enthusiastically shared their discoveries. “Did you know I wasn’t named until I was one year old? My parents followed an ancient African name-giving tradition.” As discussions unfolded, it became clear that names embodied “… a living topography, a living, interrelated place full of its own diversity, relations, multiplicity, history, ancestry, and character.”2

Inquiring into names was challenging, requiring students to reconstruct existing understandings of themselves and others. At times, some students became upset by the meaning of their name, thinking it was not as cool as their peers’. “Why does my name mean olive? It is not nearly as cool as a name meaning one with a gentle spirit.” Facing these situations required careful responses that encouraged students to immerse themselves in further historical investigations. Students worked collaboratively as research groups, supporting one another to discover the hidden history of each other’s names rooted in ancient societies: “Did you know that Olivia means olive, which symbolized peace and friendship in Ancient Greece?” Whatever challenges or triumphs presented themselves, the class learned to be in it together.

But do I belong?

Inquiring into names was challenging, requiring students to reconstruct existing understandings of themselves and others.

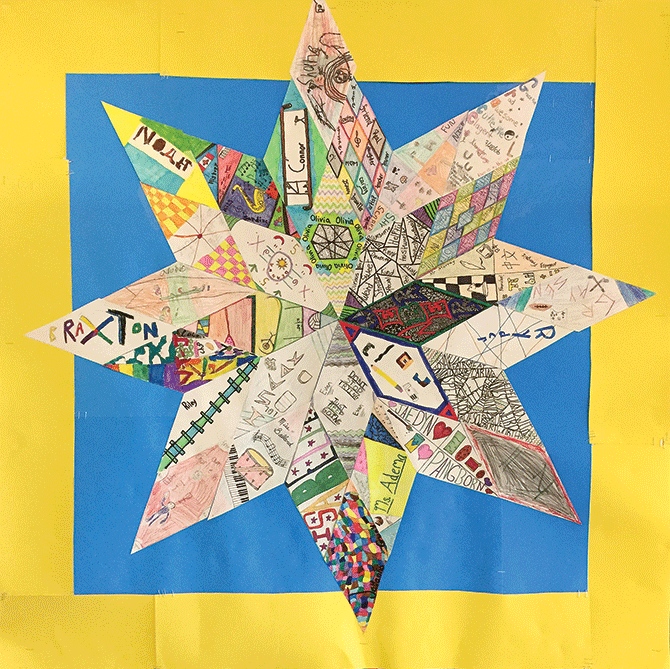

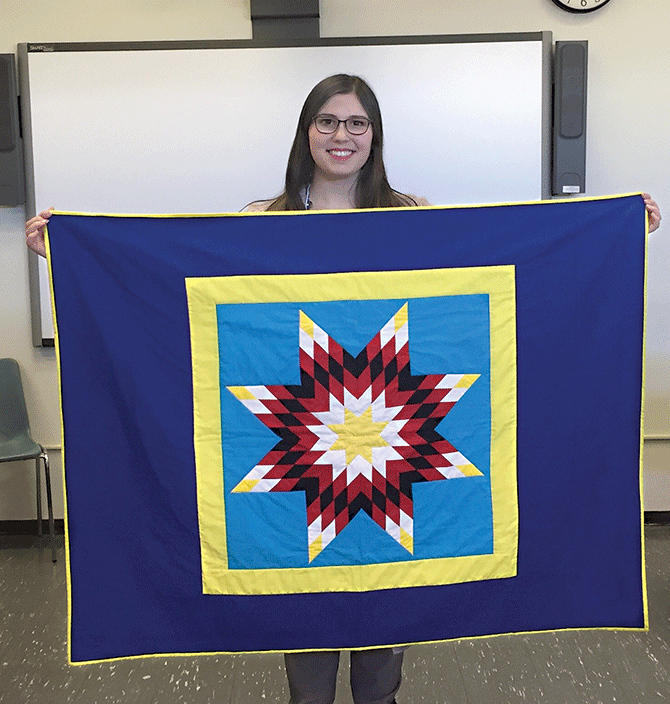

For young students, finding a community and establishing a sense of genuine belonging can be both challenging and scary. During recess or lunch breaks, students’ sense of belonging would regularly come under question due to various social encounters. To address this problem, the class created a paper star quilt to serve as a visual representation of belonging, a constant reminder that we are one community full of unique individuals with different names and histories. A group of students suggested reaching out to administration, option teachers, and school counselors, inviting them to create a piece of the quilt so as to embrace the full breadth of their community. One student explained that “although certain people may not appear to belong, every community can have and create space for difference. Everyone can belong.” Learning that Indigenous traditions require star quilts to be gifted, the class decided to give their paper quilt to the school, hanging it in the hallway outside of their classroom.

Curricular implications

Across Canada, identity is one of the foundational building blocks of most social studies programs, providing opportunities for topics such as diversity, race and gender to be explored as living experiences. Identity is at the heart of the names inquiry, tackling the existential questions “Who am I?” “Who are they?” and “Who are we?” in ways that encourage and require autobiographical investigation. With every student having a name, it yielded a starting point to uncover and grasp identity as fluid and complex, a collection of living experiences that brings into question what it means to share a Canadian identity that is multi-faceted, yet uniquely individual.

Having students grasp the fluidity of identity and accept who they are as more than their names required encouraging them to inquire into notions of identity and citizenship as they apply to their world. Through the learning process, social studies became enriched as students and teachers realized that names are a doorway into who a unique individual is and is becoming; that names are stories full of endless possibilities, best discovered in community with others.

Photos: Courtesy Katelyn Jardine

First published in Education Canada, March 2019

1 Dwayne E. Huebner, “The Capacity for Wonder and Education,” in The Lure of the Transcendent: Collected essays, by Dwayne E. Hubner (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishing, 1999).

2 D. Jardine, On the Nature of Inquiry: The individual student (Galileo Education Network, 2002).

http://galileo.org/teachers/designing-learning/articles/the-individual-student