The Foundational “R”

Self-regulation underpins reading, ’riting, and ’rithmetic – and so much more

“School days, school days

Dear old golden rule days

Readin’ and ’ritin’ and ’rithmetic

Taught to the tune of the hickory stick…”

“School days, school days

Dear old golden rule days

Readin’ and ’ritin’ and ’rithmetic

Taught to the tune of the hickory stick…”

So goes the traditional song. Times have changed, however. Though members of the educational community continue to recognize and value the necessity for children to emerge from their elementary school years having met a standardized level of traditional academic achievement in recognized subject areas, there is now a keen awareness of how children’s ability to attain calm and alert states of being impacts their learning and, thus, their overall academic success. Professional education is moving beyond the conventional 20th century construct of learning as reading, writing, and arithmetic to a more progressive, whole-child approach that recognizes the profound impact that these self-regulation skills have on long-term outcomes.

What does self-regulation look like?

On a routine basis, educators engage in practices that specifically reference self-regulation skills. When report cards are composed, when individual education plans are created for children with exceptional strengths or needs, when anti-bullying initiatives are implemented in the school setting, the core skill of self-regulation is foundational. Bruce Perry describes self-regulation as being able to take note of and control basic and complex needs and feelings, such as sleep, hunger, anger, and fear. He emphasizes that “developing and maintaining this strength is a lifelong process. Its roots begin with the external regulations from a caring parent, and its healthy growth depends on a child’s experience and the maturation of the brain.”[1]

Ontario’s Early Learning for Every Child Today[2] (ELECT), a skill- and play-based developmental, pedagogical framework from birth t0 eight years of age, incorporates self-regulation concepts that continue to develop throughout the elementary years. ELECT indicates that self-regulation starts in infancy and goes far beyond just the learned skill of sitting still and paying attention.

Through the course of a child’s development, self-regulation emerges gradually along several domains. As parents respond with sensitivity and consistency to a baby’s cues indicating the need for comfort, feeding, diapering, and/or stimulation, the infant begins to show formative signs of emotional regulation, for example by “fussing” (instead of crying) to express mild discomfort. Through these sensitive interactions, emotional regulation begins to unfold. In toddlerhood, self-regulatory development starts to extend into the realm of behaviour regulation as young children begin to respond to cues given by adults to stop or start behaviours, show an emerging impulse control with peers, and the ability to delay gratification for brief moments of time. Attentional regulation typically follows at around three years of age as preschoolers start to demonstrate the ability to focus attention, avoid distraction, delay gratification, persist when frustrated, use language to express and regulate emotions, and utilize effective strategies to self-calm. Continued and reliable acceptance and unconditional support from adults actively contributes to the ongoing evolution of these self-regulatory competencies, which continue to develop throughout childhood. The acquisition of these foundational skills and the ability to self-regulate emotions, behaviour, and attention unquestionably sets the trajectory for lifelong learning, happiness, and success.

Current understandings of self-regulation

Calm, Alert, and Learning,[3] authored by distinguished research professor Stuart Shanker, is a recent and seminal publication in the field of self-regulation. It expresses the notion that an enhanced professional understanding of self-regulation, and the implementation of appropriate strategies to support these skills, will lead to both enhanced learning capacities and “the skills necessary to deal with life’s challenge.” Shanker encourages all professionals working with children, especially elementary teachers, to enhance their students’ self-regulatory skills by integrating educational strategies that boost their ability to cope with the stressors of everyday life. The result, Shanker says, has potential to lead to an increased capacity to:

“attain, maintain, and change one’s level of energy to match the demands of a task or situation; monitor, evaluate, and modify one’s emotions; sustain and shift one’s attention when necessary and ignore distractions; understand both the meaning and variety of social interactions and how to engage in them in a sustained way and connect with and care about what others are thinking and feeling – to empathize and act accordingly.”[4]

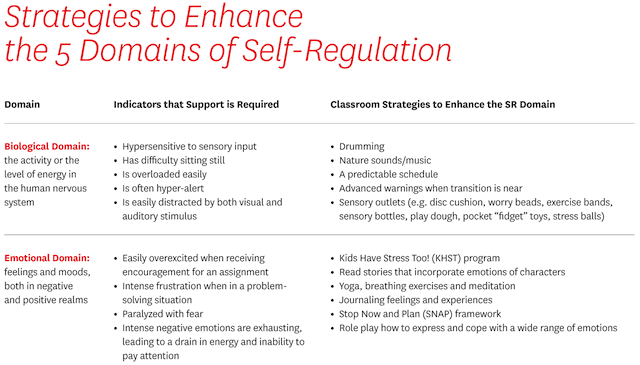

In order for all of these very complex skills to be fully cultivated, it is essential that each of the five interconnected domains of self-regulation – biological, emotional, cognitive, social and prosocial – are supported. The chart, Strategies to Enhance the 5 Domains of Self-Regulation, defines typical characteristics of each domain and offers tangible classroom ideas that support self-regulatory development, adapted from Shanker’s work.

Click the image to view the full chart

Classroom-based self-regulation teaching and learning

Upon entering Allison Labatt’s Grade 2 classroom at Westmount School in Ontario’s District School Board of Niagara (DSBN), it is immediately obvious that she takes recommendations like Stuart Shanker’s to heart. Labatt, now on her ninth year of teaching – including five years at the preschool level – supports her students equipped with both Ontario Certified Teacher and Registered Early Childhood Educator designations. Since 2012, students in her classroom spend the first few months of school explicitly immersed in the learning skills necessary for classroom-based success, as part of a detailed program developed in close collaboration with Ann Milligan, one of DSBN’s board-based instructional coaches.

The first picture book she utilized to support self-regulation was Lilly’s Purple Plastic Purse,[5] a perfect springboard for discussions about what self-regulation looks like, feels like, and sounds like – or what it does not. But a one-time effort is not enough. Labatt continually re-emphasizes concepts (e.g. self-regulation in the classroom, community, playground, and home environment), and utilizes a range of practical instructional strategies (e.g. “Austin’s Butterfly” on YouTube). She posts visual reminders in the learning environment and communicates information to parents and guardians with clear notes outlining this area of knowledge and skill development. Her teaching and tools make this high-level-learning concept clear to her students, who use the vocabulary in their everyday conversations with one another. Her examples of self-regulation are varied and diverse, including:

- Keep your classroom neat and tidy.

- Clean up a mess before you start something else.

- Help your friends if they are going to hurt themselves or if they are hurt.

- Be kind to nature.

- Use a friendly voice, then use a firm voice to solve a problem with peers.

- Be gentle with your things.

- Manage your feelings by taking some time to cool down.

- Make a plan to achieve your goals.

- Don’t cave under peer pressure.

And it doesn’t stop there. Labatt’s classes continually stop to reflect, assess, and set future goals in their own self-regulation development. For example, students rate their own self-regulation skills as excellent, good, satisfactory, or needs improvement, and record both what they are “really good at,” and an area for improvement. They use green highlighter to select examples of self-regulation skills which describe their abilities well, and use yellow highlighter to indicate skills in development. They list what they will need for success with goals related to self-regulation. They interview, role-play, read, discuss, view, listen, collaborate, problem-solve, and prompt one another.

While some students continue to struggle in areas such as everyday transitions, they learn coping skills, such as taking the initiative to move over to the table named “Australia” (after Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day[6]) for a break. As Labatt describes it, self-regulation skills “bleed into everything else” that happens in the classroom – and in life beyond it. Of course, as a professional educator Labatt expects the same of herself as she does of her students. Reflecting on her own needs as a former elementary-aged student, she takes great care in creating a well-organized classroom that models the self-regulation skills she teaches every day. In this classroom and many others, a dedication to self-regulation is clearly evident in the learning and behaviours of the very students who both contribute to, and benefit from, this positive environment that enfolds them.

Photo: Dave Donald

First published in Education Canada, January 2014

EN BREF – Cet article examine l’autorégulation en tant que fondement de la réussite scolaire, particulièrement à l’école élémentaire. Les cinq aspects de l’autorégulation (biologique, affectif, cognitif, social et prosocial) expliqués par Stuart Shanker dans Calm, Alert and Learning sont traités en fonction des éléments suivants : 1) les comportements indiquant la nécessité d’un soutien ou d’une intervention; 2) des stratégies à utiliser en classe pour rehausser le développement de chacun des aspects spécifiques de l’autorégulation en vue de susciter chez l’enfant un état calme et alerte propice à l’apprentissage. L’article inclut une interview auprès d’une enseignante à l’élémentaire ontarienne qui met délibérément en pratique l’enseignement et le modèle de l’autorégulation dans sa classe, et indique comment cette compétence joue un rôle essentiel dans ses interactions, le curriculum et le milieu. Des stratégies et des ressources pour la classe et la collectivité de même que des liens en ligne sont fournis.

[1] Bruce Perry, Keep the Cool in School: Promoting non-violent behaviour in children (2013). http://teacher.scholastic.com/professional/bruceperry/cool.htm

[2] Ontario Ministry of Children and Youth Services, Early Learning for Every Child Today: A framework for Ontario early childhood settings (2013). www.children.gov.on.ca/htdocs/English/topics/earlychildhood/early_learning_for_every_child_today.aspx

[3] Stuart Shanker, Calm, Alert and Learning: Classroom strategies for self-regulation (Toronto: Pearson Education Canada, 2013).

[4] Shanker, Calm, Alert and Learning.

[5] Kevin Henkes, Lilly’s Purple Plastic Purse (New York: Greenwillow Books, 2006).

[6] Judith Viorst, Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987).