The Creativity Question

Does schooling really kill creativity?

Why do children’s scores on creativity tests decline steeply through their schooling years? Schools have been blamed for stifling creativity, but Gerber argues there are other factors: in particular, the development of the capacity for logic and reason.

Have you ever had one of those moments where, in what seems to present itself as a sudden flash of insight, you recognize that something you had previously considered to be an unequivocal truth might not hold up quite so strongly? I have, and I’m still thinking about it, so I’d like to invite you on my journey up to this point.

Schools should foster creativity, and there are very few people who would assert otherwise. Education reform speakers call for increased focus on creativity development, and the B.C. curriculum places creative thinking as an essential target for core competency development. Yet in the last two decades it has often been suggested that schools, unfortunately, have precisely the opposite effect – that schools kill creativity.

Sir Ken Robinson made this idea popular in his viral Ted talk, “Do Schools Kill Creativity?”1 Citing research that sought to measure creativity in populations of people, Robinson projects a wonderfully impactful chart which illustrates the percentage of people who score at the genius level by age group. The trend is staggeringly clear; a straight down-angled line connects the data points between five-year-olds who score in the genius range for divergent thinking (at 95 percent), ten-year-olds (32 percent), and 15-year-olds (10 percent). “There is something happening to our children,” Sir Ken remarks. “School kills creativity, and that has to change.”

The polemical nature of the “school kills creativity” proclamation is effective for instilling a passion for change and better serving students, but it also causes me to wonder: are schools, in fact, the raison d’être for the decline of students’ creativity as they proceed through the education system?

Or is it possible that we are not considering the larger picture?

Think back to when you were young, as far back as your memory allows. I recall running about the house with a towel adorning my shoulders – convinced, unequivocally, that human flight was in my immediate future. One more push, a more forceful thrust of my arms, or jumping a little higher… I knew it was only a matter of when and not if I would fly like Superman. I’m guessing that you can also recall examples that showcase your childhood creative genius and belief in possibility. I can’t imagine that our God-given abilities are so easily lost as a result of our education system.

There are some things other than schooling that take place during those years of growth that, I believe, may have more to do with explaining our diminishing creativity – something less sinister, and something more sinister. Let’s consider these in turn.

The dawn of reason

First, as we age we grow in our ability to think, or to ratiocinate, which literally means to process and consider rationally and logically. When I was a child, I believed that a hero-esque endowment of flight was possible, and I acted according to that belief. I jumped. I leapt. I bounded into the air off flights of stairs, couches, and bookshelves. Over time – thankfully not too much time – the bruises and sprained ankles taught me that my belief might not reign within reasonable expectation. And as I think of this, I recognize something profound: reason tempers creative expression. I wonder, is it possible that Sir Ken’s measurement of creativity, exemplified by how many uses an individual can think of for a paper clip, favours quantity and not the quality of divergent thinking?

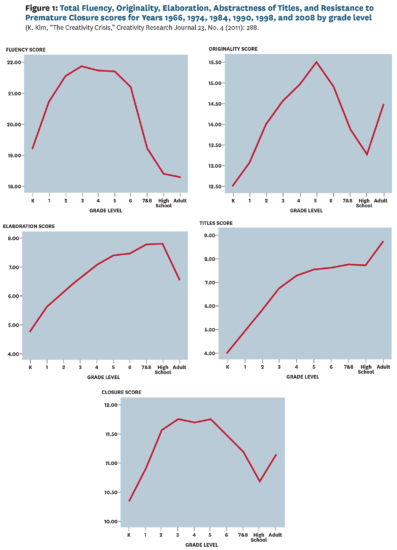

As one’s ability to think and reason increases, we should expect that many creative inclinations are filtered. I have bad, yet innovative ideas frequently, but I don’t act on or share them because I recognize that they don’t merit an audience. Older people will presumably not think of as many uses for a paper clip because they know what a paperclip can (and can’t) do, and thus discard possibilities that seem to lack value. The expression of creative ideation is reduced as a natural consequence of growth, development, and the maturation of logical thinking – not necessarily by being choked out by the hands of schooling. In fact, Kyung Hee Kim’s research shows that although a student’s creative Fluency score decreases as he progresses through the grade levels, his ability to elaborate on ideas, diversify areas of consideration, and stick with and develop ideas increase over the same timeframes.2 (For graphs of every measure tracked in this study, see below:)

Embracing possibility

But there is also something more sinister which comes into play – something that begins as a small weed and often grows over the years, potentially muting our willingness to engage our innate creativity. As many of us age, we stop believing in possibility, an essential ingredient fueling curiosity, the desire to explore,3 and one’s investment in creativity. Schooling, as Sir Ken Robinson points out, plays a significant role in shaping the thinking habits of children. Many teachers focus on the attainment of specific knowledge and thereby perpetuate a foundational ideological alignment with the idea that there always exists a “right” answer. Being “right” is rewarded. Being “wrong” is stigmatized and often penalized. Too often, content-focused teaching fails to recognize that a student’s ability to be “wrong” is an essential ingredient for seeing and pursuing possibility.

Creativity empowered breeds revision. It is fostered through a willingness to try, recognizing that there is always more we can learn through experiencing failure.

Failure left uncelebrated feeds into new conceptualizations of limitation. My dream of human flight died with my final plop to the floor, accompanied by the laughter and ridicule of siblings. What might have become of my passion if I had been encouraged to rework the idea, to trade in the towel-cape and seek out increasingly reasoned approaches? (Perhaps the Wright brothers had similar beginnings.) Creativity empowered breeds revision. It is fostered through a willingness to try, recognizing that an idea only dies when we accept our last failure as final.4 There is always more we can learn through experiencing failure.

It is, then, the role of the teacher to foster seeing possibility by reframing failure, to take time to consider whimsy, and to teach students how what might first be regarded as a bad or weak idea can often be reworked into a good one. Focus on asking questions over providing answers – on exploration over giving directives. Provide students with time to reason through the merit of their ideas. Facilitate and coach students to think by considering the answers to the questions, “What if?” or “How might?” or “What’s next?”5

I have never met a teacher who entered the profession with a vision of producing die-cut student minions. Instead, they became teachers because of a deep desire to help students live into and reach their potential. We learn (and teach) so that we might expose new potential solutions, insights, or abilities and then press into, or live into, those possibilities. Teachers strive to recognize possibility within the landscape of every student’s individual giftedness, then work to nurture their unique complement of talents.

How do we do this?

Spend time dreaming, on your own and with your students. Acknowledge that sometimes the dreams that seem crazy may just be the seed of the next idea that changes the world, then empower an attitude to try. Shakespeare said it well in Measure for Measure: “Our doubts are traitors and make us lose the good we oft might win by fearing to attempt.” If we give up on something, it is finished. Where we continue to believe in possibility, creativity knows very few limits.

Photo: iStock

First published in Education Canada, June 2020

NOTES

1 TEDTalks: Sir Ken Robinson, “Do Schools Kill Creativity?” (New York, N.Y: Films Media Group, 2009).

2 K. Kim, “The Creativity Crisis: The decrease in creative thinking scores on the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking,” Creativity Research Journal 23, no. 4 (2011): 285-295.

3 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, How People Learn II: Learners, contexts, and cultures (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2018), 149.

4 R. Beghetto, “Taking Beautiful Risks in Education,” The Arts and Creativity in Schools 76, no. 4 (2018): 18-24.

5 Kolb, David & Kolb, Alice. (2017). The Experiential Educator: Principles and Practices of Experiential Learning.