Myths & Facts about ADHD in Children

Implications for educators

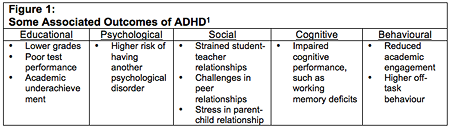

From time to time, all children are inattentive, hyperactive, and impulsive. In fact, it is normal and expected at various developmental stages to exhibit more or less inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. At mild to moderate levels, these characteristics and behaviours tend to be transient and do not significantly interfere with normal functioning. However, when inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity become severe and persist across different settings, they can have detrimental effects on many aspects of a child’s functioning. Children who meet diagnostic criteria for Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) experience more severe symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity and consequently tend to experience significant challenges in various domains (psychological, behavioural, social, etc.) and across multiple settings. Figure 1 provides some examples of various outcomes associated with ADHD in relation to different areas of functioning.

With regards to school functioning, children with ADHD experience significant impairments with far-reaching and lifelong implications. At the preschool level, children with high levels of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity face challenges in their relationships with their teachers and peers, as well as difficulties building basic literacy, math, and language skills. At the elementary school level, these difficulties often persist and can even become more severe, resulting in continued academic struggles for these children. Not only do they experience lower grades, poor test performance, and academic underachievement, they are also more likely to be placed in special education and to be suspended or expelled for behavioural problems. This trajectory often continues at the high school level, where teenagers with ADHD continue to struggle. They tend to have lower academic attainment, as well as more behavioural and academic problems. In adulthood, those whose difficulties persist face challenges in developing and implementing the skills necessary to succeed in postsecondary education and stable employment.2

Myth #1: Hyperactivity and impulsivity are the main causes of academic problems for children with ADHD.

Hyperactivity and impulsivity can be very challenging to deal with in the classroom, and one might assume that these symptoms are the key cause of the school-based difficulties faced by children with ADHD. This is not the case. Rather, research consistently shows that inattention is the most significant factor associated with the academic problems faced by children with ADHD.3 This has important implications for how ADHD is addressed in the school setting. This is not to say that these behaviours should be ignored, but rather that interventions targeting problematic behaviours should go hand in hand with interventions designed to target inattentive symptoms.

Myth #2: ADHD is a behavioural disorder

Another misconception about ADHD surrounds its classification. Given the behavioural manifestations of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, one might conclude that ADHD is a behavioural disorder and until recently it was classified as such. However, an abundance of neuroscience research now unequivocally demonstrates that ADHD originates in the brain. As such, ADHD is now classified in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as a neurodevelopmental disorder,4 emphasizing its neurological and biological origins in the childhood period.

Myth #3: ADHD symptoms are localized to a single brain region

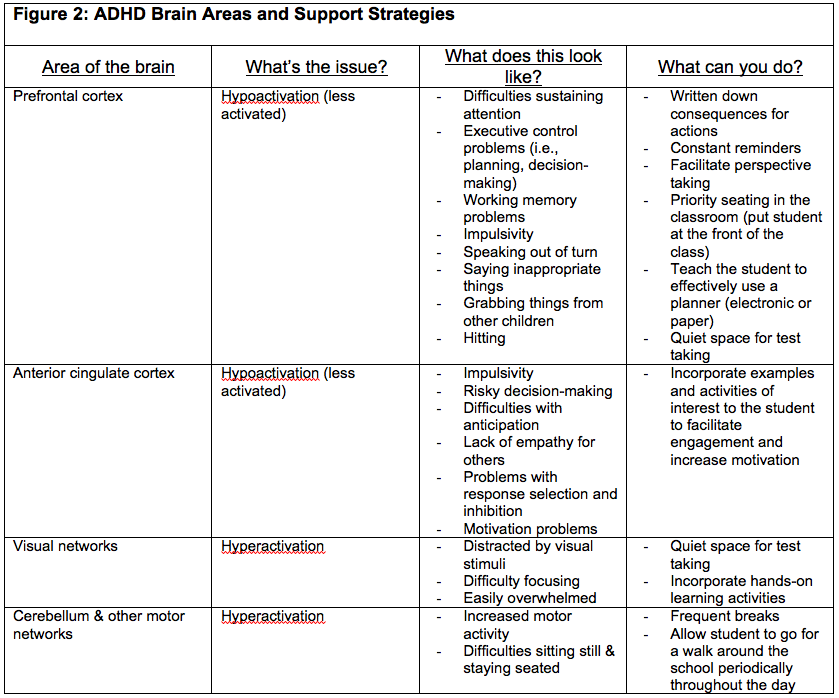

ADHD does not involve just one part of the brain, but rather is related to dysfunction in several areas. Previous understandings of the neurobiology of ADHD suggested that only the frontal-striatal circuits were dysfunctional; however, new research suggests that several other areas of the brain contribute to ADHD symptomatology,5 specifically, the cortical regions, subcortical regions, and the cerebellum. Specific areas within each of these regions are related to different symptoms and behaviour.

These diverse brain areas are associated with an array of behaviours and functions. We can understand how these areas of functioning relate to ADHD by examining what is happening in each of these areas in individuals with ADHD. This is done by using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to look at the activation patterns in the brains of individuals with ADHD, and comparing the patterns to those without ADHD. It is also important to note that individuals with ADHD often have co-occurring problems that may also impact the structures and functions of other brain regions.

Myth #4: ADHD only involves over-activation of associated neural areas

There is a popular misconception that brain areas are over-activated for individuals with ADHD, likely because many overt behaviours associated with ADHD involve overactivity and hyperactivity. In fact, it has been established that ADHD actually involves both hypoactivation (underactivation) and hyperactivation (overactivation) of brain regions.6 Different patterns of activation are seen in different areas of the brain.

For instance, the prefrontal cortex has been found to be hypoactivated (less activated) when required to engage in inhibitory responses in individuals with ADHD compared to those without ADHD.7 Hypoactivation of the prefrontal cortex causes executive function and working memory impairments. Further, the anterior cingulate cortex has also been identified as being hypoactivated in individuals with ADHD.8 The anterior cingulate cortex is involved in anticipation, impulse control, empathy, decision-making, and emotion. Therefore, hypoactivation in this area results in impulsivity, poor/risky decision-making, difficulty anticipating rewards/consequences and right/wrong, as well as problems with regulating emotion.

By contrast, the visual systems and motor systems within the brains of individuals with ADHD appear to be hyperactivated. Hyperactivation of these areas results in increased distractibility, and increased motor movements and behaviours, such as fidgeting, moving around, and appearing as if the child is being run by a motor. Figure 2 summarizes the various areas of the brain that have been identified as being hypoactivated or hyperactivated in individuals with ADHD and provides some strategies that educators can use to address these difficulties.

Myth #5: The neurological correlates of ADHD are completely understood

There is still much to be discovered about the neurobiological origins of ADHD. Although many brain regions have been implicated in the development and presentation of ADHD, there has been some disagreement on which areas are most influential. Furthermore, ADHD often co-occurs with other disorders, meaning that when a child is diagnosed with ADHD, it is very likely that they have another diagnosis, such as a learning disorder or a behavioural disorder.9 Co-occurring disorders make it difficult to distinguish which brain areas are involved with each disorder.

Myth #6: Biological treatments are the only option for children with ADHD

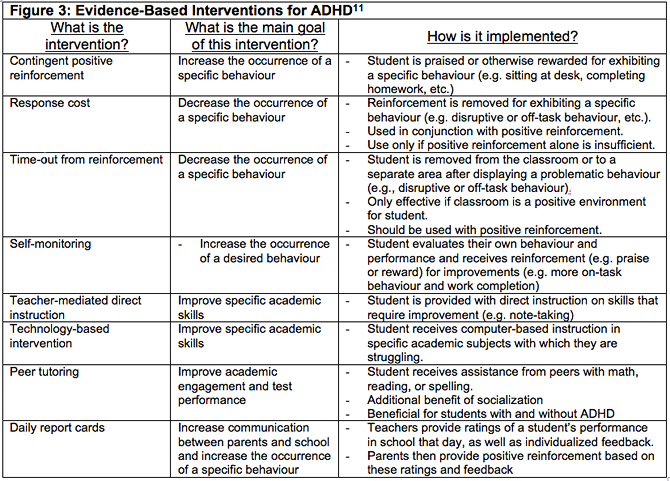

Indeed, there are many things that parents and educators can do to help their students with ADHD. The research has shown that behavioural and psychosocial interventions can be effective for treating ADHD symptoms.10 While medications also have their place in treating ADHD, the message here is that there are school-based options available that can be implemented by educators themselves. Figure 3 provides a summary of some evidence-based interventions for ADHD, as well as tips on how they can be implemented.

THOUGH MUCH REMAINS to be learned about the neurological correlates of ADHD, it is clear that ADHD is a complex disorder that affects many aspects of functioning, both in and out of the school setting. Educators have a critical role to play in the life of a child with ADHD and are ideally situated to implement helpful strategies to improve academic performance and behaviour, consequently benefitting the well-being and learning experiences of children with ADHD.

Special thanks to Stacey Kosmerly, Julia Boggia, and Natt Dugan at the University of Ottawa’s ADHD & Development Lab for their invaluable contributions and assistance in the preparation of this article.

The Importance of Positive Relationships

Emerging research suggests that strained or negative relationships with parents and teachers can adversely affect the learning outcomes for children with ADHD.11 In the school context, new research suggests that educators can enhance immediate and long-term success in their students with ADHD by improving their relationship with these students. Strategies for strengthening the teacher/student relationship can include:

- Make an effort to connect with students on an emotional level.

- Show interest in your students’ progress.

- Offer encouragement and support.

- Support your students’ autonomy to make their own choices and take ownership of their education.

- Avoid controlling language.

- Avoid using coercion and punishment, when positive alternatives can be used instead.

- Reach out for support for yourself in your role as an educator.

- Work on building a positive parent-teacher relationship.

1 Maria Rogers, Julia Boggia, Julia Ogg, and Robert Volpe, “The Ecology of ADHD in the Schools,” Curent Developmental Disorders Reports 2, no. 1 (2015): 23-29.

2 D. Daley and J. Birchwood, “ADHD and Academic Performance: Why does ADHD impact on academic performance and what can be done to support ADHD children in the classroom?” Child: Care, Health and Development 36, no. 4 (2010): 455-464.

3 A. Garner, B. Connor, M. Narad, L. Tamm, J. Simon, & J. N. Epstein, “The Relationship between ADHD Symptom Dimensions, Clinical Correlates and Functional Impairments,” Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 34, no. 7 (2014): 469–477.

4 American Psychiatric Association and American Psychiatric Association DSM-5 Task Force, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, 5th ed. (Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

5 E. M.Valera, S. V. Faraone, K. E. Murray, and L. J. Seidman, “Meta-Analysis of Structural Imaging Findings in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder,” Biological Psychiatry 61, no. 12 (2007): 1361-1369.

6 H. McCarthy, N. Skokauskas, and T. Frodl, “Identifying a Consistent Pattern of Neural Function in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A meta-analysis,” Psychological Medicine 44, no. 4 (2014): 869-880.

7 McCarthy et al., “Identifying a Consistent Pattern of Neural Function in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.”

8 George Bush, “Cingulate, Frontal, and Parietal Cortical Dysfunction in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder,” Biological Psychiatry 69, no. 12 (2011): 1160-1167.

9 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5.

10 G. A. Fabiano, W. E. Pelham, E. K. Coles, E. M. Gnagy, A. Chronis-Tuscano, and B. C. O’Connor, “A Meta-Analysis of Behavioral Treatments for Attention-deficit/hyperactivity Disorder,” Clinical Psychology Review 29, no. 2 (2009): 129-140.

11 George J. DuPaul, Lisa L. Weyandt, and Grace M. Janusis. “ADHD in the Classroom: Effective intervention strategies,” Theory into Practice 50, no. 1 (2011): 35-42.

12 Maria Rogers and Fiona Meek, “Relationships Matter: Motivating students with ADHD through the teacher-student relationship,” Perspectives on Language and Literacy (2015): 21-24