Manitoba’s Moratorium on School Closures

What has it achieved, what is next?

In 2008, school boards in Manitoba had identified nine out of the province’s roughly 700 schools for possible closure. Four of those schools were in the Louis Riel School Division in southeast Winnipeg. The schools were small but they were viable. In response to vigorous community concern, the provincial government passed legislation that imposed a province-wide moratorium on school closures and required Ministerial approval for any planned closure or consolidation. That measure effectively halted the closures in Louis Riel – but it also halted closure discussions everywhere in the province. Some school divisions were forced to maintain schools whose enrolments weren’t viable, to the point where parents literally walked away, abandoning the school.

Like all other Canadian provinces, Manitoba has had to address the challenges of matching school facilities and programs to shifting student enrolments. Decisions about whether or not to close or consolidate existing schools, and/or open new ones, often have far-reaching consequences, especially in rural communities. This article examines how the Manitoba moratorium has impacted on these critical decisions.

Bill 28: The Strengthening Local Schools Act

Bill 28: Strengthening Local Schools (Public Schools Amendment Act) was introduced without consultation in April 2008 and enacted into Manitoba law on June 12. Under the heading “Moratorium on closing schools,” this legislation states that, “except with the Minister’s written approval under this section, a school board may not close a school that pupils attended in the 2007-08 school year.”1 Laying down the conditions under which approval might be given, the legislation states that Ministerial approval may be forthcoming if the school board demonstrates to the Minister’s satisfaction that:

(i) the closure is the result of a consolidation of schools in the area or community;

(ii) there is a consensus among parents and residents of the area served by the school that the school should be closed; or,

(iii) it is no longer feasible to keep the school open because of declining enrolment and, despite having made reasonable efforts, the board has been unable to expand the use of the school building for appropriate community purpose.

In addition, the Bill required school divisions to use their best efforts to ensure that children’s travel time to and from school did not exceed one hour each way and added, “schools whose future sustainability and viability is threatened by low enrollments” to the criteria for schools that might have access to provincial community schools programming and funding. The legislation also signaled the government’s intent to provide new school closure regulations.

Peter Bjornson, then-Minister of Education, Citizenship and Youth, cited the importance of local public schools to the quality of educational experience for young children, and to the overall life of communities, as a rationale for the Act.2

Suggesting that the moratorium was a temporary measure, the Minister further stated that “over time, possibly several years, the power of school closures will be returned to school divisions, but with a new regulatory framework that emphasizes the need to work to ensure the viability of schools and their surrounding communities.”3 He also gave notice that notwithstanding the conditions for approving school closures laid out in the legislation, Bill 28’s primary purpose was the imposition of a moratorium, stating, “… I want to make it clear that the primary objective of this bill is to help keep schools open, not to find alternative ways and means of closing them.”4

Minister Bjornson clarified that he would only consider consolidation as a justification in rural Manitoba and it would only apply to the merging of an elementary school with a neighbouring high school to form a Kindergarten to Grade 12 school – and only then in an extreme case where one school could clearly not remain viable.5 Further, it was made clear to school boards that “consensus among parents and residents of the area served by the school” meant very close to if not total endorsement of any school closure plan. This was a “hard” moratorium.

The response to Bill 28

School closures are more often than not contentious, and it was no surprise that Bill 28 provoked strong responses, with nearly 50 presentations and submissions made to the legislative Standing Committee on Social and Economic Development at the second reading of Bill 28.6 Opposition to the legislation was led by school boards as well as the Manitoba Association of School Trustees and the Manitoba Association of School Superintendents, while parents and parent councils generally supported the bill.

School boards asserted that in the face continuing declining and shifting enrollments, they needed the option of school closures or consolidation as one way of addressing local circumstances in a way consistent with local community and taxpayers’ needs. They also argued that the one-hour busing limitation failed to recognize the geographical realities of certain communities and could prevent vocational programming for some rural students. Further concern was expressed that the Minister did not provide for the additional costs borne by the divisions for keeping very small schools open, and that the legislation did nothing to address the underlying causes of school closures.7

Parent Councils and individual parents speaking in favour of the Bill cited research on the benefits of small schools and highlighted the negative impact that school closures are likely to have on families and the surrounding community. They expressed concern about the negative educational effects and safety issues associated with busing children long distances to school. Several presentations argued that although the pre-existing guidelines called for extensive community consultation before school closing, this was not always happening and that school boards could too easily manipulate the process. Further, it was suggested that the proposed School Closure Regulations could provide an opportunity to address a perceived imbalance between the authority of school boards and communities and to restore ministerial oversight.8

The impact of Bill 28

Minister Bjornson described Bill 28 as providing a period of stability to allow governments, school boards and communities to develop better solutions to declining enrolment and cost pressures.9 Nine years later, the moratorium is still in place. So how successful has the legislation been in 1) slowing down school closures in the province, and 2) developing creative ways to sustain schools with declining enrolments in ways that are both educationally and financially viable?

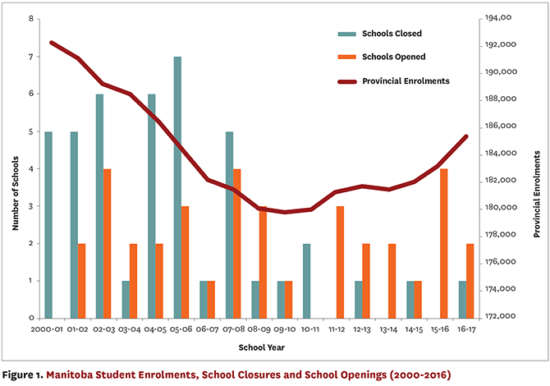

The moratorium has not completely ended school closures in the province, but it has substantially reduced the number of schools being closed and extended the time it takes to actually close those schools that are approved. According to data from the annual Manitoba Student Enrollment reports, in the eight years before the 2008-09 school year, some 37 schools were closed across the province. In the eight years from 2009-10 to 2016-17, only six schools were closed (see Figure 1).

Five of those schools were rural – all with enrolments of under 20 students – and they closed less as the result of sustained planning than because “parents voted with their feet and took their kids to larger schools, leaving schools empty.”10The impact on Winnipeg divisions has been more marked. Faced with the likelihood that even after a lengthy consultation process, any divisional proposals that involved a school closure or consolidation would not receive Ministerial approval, urban school divisions essentially took closure and consolidation off their agendas and since 2008, only one Winnipeg area school has been closed.

The extent to which these developments can be taken as evidence that the moratorium has stimulated school divisions to rethink their approaches to managing their facilities in ways that sustain the educational and economic viability of small schools is a more complex question to answer. The moratorium has certainly discouraged school boards from seeing school closure, or even consolidation, as anything but a “last resort” option (if it ever was anything else), and it also made more rigorous the expectations of parental and community consultation, in which divisions must present a detailed and compelling justification for their proposals and from which they must demonstrate to the Minister strong community support.

Below, we look at two cases that illustrate quite different impacts from the moratorium. In the Louis Riel School Division, a revisiting of facilities and programming enhanced the viability of community schools previously scheduled for closing, while in the Pembina Trails School Division, the effect may have been only to delay the closing of a school – at a substantial cost and without any obvious benefits.

Reconfiguring divisional programming

The moratorium on school closures effectively halted a significant reorganization of schools in Louis Riel School Division that had included the closure of four smaller schools. All had enrolments between one and two hundred. Seven years later, in 2015, Louis Riel faced enrolment dilemmas similar to those faced in many urban divisions: Enrolment was growing in new subdivisions and shrinking in older neighborhoods. French Immersion enrolment was up; English program enrolment was down. Louis Riel initiated a broad community consultation process. After ten large-scale community forums involving the input of thousands of parents and community members, Louis Riel implemented a reorganization that changed catchments, grade configurations and language designations for several schools. Today, all four schools originally identified for closure are still open. Three of the four were positively affected by the 2015 reorganization and by subsequent neighbourhood development, and are more viable today than they were in 2008. The fourth school remains small but is still viable. This more recent reorganization was supported by the provincial government, as the school division sought to rationalize its existing facilities rather than ask for new ones.

The closing of Chapman K-6 School in Winnipeg

Chapman School had been scheduled for closure when Bill 28 was introduced. With a capacity for 225 students, this Winnipeg K-6 school had some 87 students registered in 2007 – only half of whom actually lived in the school’s catchment area. The divisional plan was to move the Chapman students to the neighbouring Royal School, which had a capacity for some 500 students and an enrolment of around 200. All of the students living in the Chapman catchment area also lived within 1.6 km of Royal School. The position of the board was that the quality of education would be equal or superior at Royal School for Chapman students, while the annual incremental cost of keeping Chapman School open was approximately $500,000.

Under the moratorium, requests to the Minister to close Chapman School were rejected on the grounds that there was not a supporting consensus among parents and community members. In the words of Superintendent Ted Franson, “the Minister made it clear that consensus meant everyone.” During the 2015-16 school year, the Chapman School Parent Council initiated a conversation about closing their school along with some requested accommodations related to moving their students to Royal School. These requests were agreed to, and all 31 parents of children registered at Chapman School asked that their children be transferred to Royal School. A request to close the school in June 2016 was submitted to the newly appointed Minister of Education, the Honourable Ian Wishart, and approved.

When Bill 28 was introduced, the Minister indicated that it was intended to be in place only for a few years, after which authority over closures would be returned to school boards, framed by a new set of provincial Regulations. The moratorium is now in its ninth year of operation and there are no Regulations. In April 2016, the provincial election saw the New Democratic Party government, which had been in power since 1999, replaced by a Progressive Conservative government. With the new government comes the possibility of a reconsideration of the moratorium and the development of a set of regulations to structure the process of review and closure or amalgamation of schools.

The complex array of community settings across remote, rural and urban contexts in the province call for flexible and creative thinking about the funding and delivery of high-quality school programs to all Manitoba students. The moratorium on school closure in Manitoba has, however, framed the discussion of small schools as “to close or not to close,” narrowing to a single and sometimes stark choice the question of how we make prudent use of our capital and operating dollars and maintain strong, vibrant schools. It is this broader discussion that the province now needs to engage in more fully.

En Bref : En 2008, le Manitoba a imposé un moratoire, encore en vigueur, sur les fermetures d’école. Les auteurs de cet article retracent l’historique du moratoire et expliquent son impact sur les écoles manitobaines.

Photo: iStock

First published in Education Canada, June 2017

1 For this and all subsequent quotations from the Act: Government of Manitoba, Bill 28: The Strengthening Local Schools Act (Public Schools Act Amended), 2008.

2 Government of Manitoba, “Bjornson Introduces Legislation that Would Place Moratorium on School Closures (April 28, 2008: Manitoba Government News Release). http://news.gov.mb.ca/news/index.html?item=3588

3 Manitoba, Legislative Assembly, Debates and Proceedings (Hansard), 39th Leg, 2nd Sess. Vol. LX, No 40B (May 13, 2008), 2101.

4 Manitoba Legislative Assembly (May 13, 2008), 2101.

5 “Closure Ban Has Boards Confused,” Winnipeg Free Press (May 12, 2008): A4.

6 K. Antonyshyn, “Bill 28, The Strengthening Local Schools Act (Public Schools Act Amended),” Manitoba Law Journal 34, no. 3 (2011): 1-34.

7 Antonyshyn, pp. 22-3.

8 Antonyshyn, pp. 19-21.

9 Manitoba Legislative Assembly (May 13, 2008), 2101.

10 “Advice on School Closings Ignored: Report,” Winnipeg Free Press (July 27, 2016). www.winnipegfreepress.com/local/advice-on-school-closings-ignored-report-388496241.html