Propelling Beyond Boundaries

An Exemplary Classroom at Work

Paige Fisher

As a teacher educator at Vancouver Island University, I take my student teachers on an assessment field trip so they can witness the ways that inquiry and formative assessment can be embedded in instructional practice. We go to a local elementary school to visit an exemplary classroom. Mary-Lynn Epps and Kerry Armstrong share this Grade 7 classroom – Mary-Lynn as the enrolling teacher, and Kerry in the role of learning and technology support and science instruction.

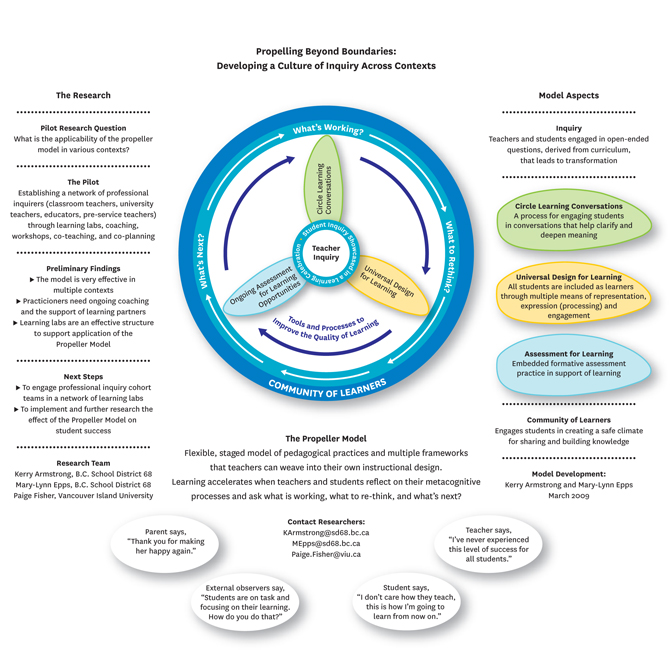

These teachers have developed a small network of inquiring teachers within their school and at other schools in their district, and they are collaborating to develop powerful learning environments for their students and to inquire into their own instructional practices. They have reflected deeply on what has been working in their classrooms and created a metaphor for their practice, which they call the Propeller Model (see diagram). Their work is having a significant impact on their learners as well as on their own understanding of teaching/learning processes. I am hopeful that exposure to this classroom will deepen my students’ understanding of powerful learning environments as they move forward in their teacher education.

I have informed my students that, although it may not be apparent at first glance, some of the students in this classroom have profound and diverse learning needs. When we arrive, we file into a fairly typical classroom. There are posters and criteria sheets covering the walls, desks arranged in small groups, a bank of four computers, and a large meeting table at the back of the room. Mary-Lynn is in the process of organizing the group for the upcoming work period. We are asked to observe while she gives the students their instructions, then we are invited to listen to student and teacher conversations, or to interact with the students.

“Ok everyone,” Mary-Lynn says, “the student teachers are here to observe, and they might want to ask you questions, but this is a working period, so try to stay focused on your responsibilities. We have information circle meetings today, and you need to be prepared with your notes before you come to the meeting. Get together with someone else in your working group and share your notes with each other. That way you can add to your own sheet and you can help make sure your partner is prepared. Remember the inquiry question is ” One well, one wish. Water has the power to change everything. What will you do to transform yourself and others to ensure there is a well for the future?”

“Use the posted criteria to make sure you’re on the right track”, she says, “and I would like you to use the A-P-E strategy to give each other feedback. Could someone please tell the student teachers what this means?”

Megan puts up her hand. “It’s, um, it’s the thing where each of us has a job, like Adviser, Presenter, and Encourager. We have to take turns being each one and give each other feedback using the criteria.”

“Thank you Megan. While each group meets with me, the rest of you will do A-P-E with your working groups. If you finish that, please begin to add more details to your Mind Maps. We should be able to get through at least three group meetings this period.”

One group of students moves to the meeting space at the back of the room while the rest of the students settle in and a productive buzz pervades the room. I can hear students sharing information and giving each other feedback on their work in progress. I follow one of my teacher education students, who is moving to join a working group. “I never did this kind of thing when I was in school,” she says to one of them. “How do you like working together like this?”

“Well, the best thing about working with other people is how they have other ideas and how that makes my ideas bigger and better,” replies a boy in the group. “I feel like I learn a lot from the other kids and it helps me see all the different ways there are to do things.”

One of the other boys in the group is sharing notes that are stored on his laptop. “Wow, you’re allowed to use a computer?” my student asks.

“Yeah, anyone can use the computer if they want to, but I really need it. This graphic organizer I’m using helps me to organize my thinking. The computer helps me put my thinking on paper, and that is a good thing because I can come back to it, then I have something to share with the rest of my group. I have a hard time with reading and writing and I used to fall behind. Mrs. Armstrong showed me how to get the same textbooks as the other kids from files on the computer, and I use read-aloud programs like ‘Wordtalk’ and ‘Kurzweil’. Now I can copy and paste important words and ideas and even the pictures from the textbook into my graphic organizer so that when I go to Information circles, my notes are complete.”

My students and I are shaking our heads in amazement. We are struck by the environment of collaborative productivity and purposeful focus that seems to pervade the room.

Another one of my students ventures over to the group. “Can I ask you a question?” she says to one of the girls. “How does this inquiry question thing work?”

“Oh that,” she says. “It’s kind of like the main idea of what we’re doing. So, when you’re reading fiction or nonfiction, you know the idea is important if it can relate back to the inquiry question.”

“Yeah,” chimes in another girl. “Inquiry in this class helps you know what you are looking for so you don’t write down just random information. We get all this information in our groups and we share it at the information circle meeting. Then we get to come up with our own question and we have a showcase where we invite other kids and our parents and we show all the work we’ve done and what we learned. For our last unit on Healthy Living, I did this cool inquiry about whether computer games were making people more or less healthy. I really believe I was able to change other people’s opinions on health.”

My students and I are shaking our heads in amazement. We are struck by the environment of collaborative productivity and purposeful focus that seems to pervade the room. The students are eager to talk about their work, and to show us the things that are supporting their learning. We are especially impressed by the sense of ownership they express through their responses – not just ownership over their learning processes, but ownership of the learning of their peers as well. I know that Mary-Lynn and Kerry have worked hard to establish a Community of Learners culture in this room, and the evidence of this facilitation is playing out in the interactions my students and I are observing.

At the back of the room the first group gathers around a large table with Mary-Lynn and the information circle meeting begins. Students have been asked to share the information they have gathered so far about water. “Would someone please volunteer to start by sharing the key points you’ve brought to the meeting? As you share, be sure to summarize how the information is meaningful to the overall inquiry. Think about your connections and how they help you to transform your thinking and beliefs about water. The rest of you remember that your job as a listener is to ask questions to help you understand and to jot down ideas that you think will help you to answer the inquiry question.” We hover at the edges of the meeting and listen in. Throughout the meeting, Mary-Lynn facilitates the discussion by providing descriptive feedback, asking probing questions, and inviting responses from each member of the group.

“Great work, everyone” I hear Mary-Lynn say as the meeting concludes. “I’ve been really impressed with what you’re bringing to the circle, and the way you’re adding to all of our learning. Make sure you complete the self-assessment of your group participation before you go back to your desks please. Once you get there, remember your first job is to do a reflective write on what you learned during the meeting. Then you can move on to your Mind Maps.

I quickly follow some of the students back to their desks so that I can ask them about the meeting. “Could you please tell me a little bit about your circle meetings?” I ask. “What are they like for you?”

“It helps me,” says Christopher, “Because when there is a part of the book that you don’t understand you can just ask someone in the group or bring it up and it will make it easier to understand and they’ll like describe it to you so you get a better grasp of the idea.”

“I really like it too,” says Tran. “Information circles help me with my learning and on my tests because every time I go to a meeting I always get a good idea back. Like if other people talk about things that I don’t have on my paper I can write it down, and when I have a test I can use the things I wrote down on my paper to get a full score.”

I shift my attention to a group that is working on their Mind Maps. One of the student teachers is asking what they are and how they work. The group is eager to respond. “They’re kind of like a word web, but we use pictures and symbols to help make sense of ideas, and then we look for connections between them.”

“How do they support your learning?” she asks.

Blake replies, “They help me because you don’t have to go through the tedeism of writing down a huge list of words on paper and then forgetting what half of them mean by the end of the day. They let you write pictures down and to organize your words and your pictures in a convenient way so you can remember them all.”

Other students in the group comment on how they are able to use their Mind Map to help them study for tests. “I can look at a picture or symbol and it helps me make connections to other facts about the inquiry. It’s an easier way to remember ideas without trying to memorize a list of notes.”

“How do you know what to put on them?”

“We look at lots of examples and we set criteria with the teacher. We get lots of chances to share our ideas, and we get lots of feedback when we do peer and self-assessment and from our teacher.”

“This is so cool!” one of my students comments. “What happens if you go to Grade 8 next year and none of your teachers does stuff like this?”

“I don’t care how they teach me next year, this is how I’m going to learn from now on,” one of the girls responds vehemently. “This totally works for me!”

I am astonished at these students’ ability to talk about their own learning processes and I am consistently impressed by their enthusiasm and the ownership they seem to feel. They convey a real sense of pride when we show interest in their learning.

The bell rings for the lunch break, and we all move to a debriefing session. The teachers show us their Propeller Model of Learning, and they relate each component back to the classroom experience we have just had. The student teachers are bursting with questions and full of enthusiasm for the possibilities they have witnessed in this classroom. For the next several weeks we will refer back to this classroom visit as we explore the possibilities inherent in classrooms that embrace formative assessment and inquiry.

The Propeller Model

Kerry Armstrong and Mary-Lynn Epps

The Propeller Model of Learning is built upon the concept of the Community of Learners. At the beginning of each year we take the time to develop a vision with the students that outlines the attributes we would need to ensure the success of everyone in the class. The students can then begin to develop the metacognitive skills to help them take responsibility for their own learning. This classroom culture is necessary for the group to continue evolving in their ability to use the learning processes outlined throughout the entire model.

Propeller Model processes revolve around inquiry questions that guide the momentum of learning throughout each inquiry. We begin by designing an overarching question based on concepts derived from provincial learning outcomes. Our goal is to transform students’ thoughts, actions, and beliefs related to the overall topic. Once students have enough background knowledge, they begin to create their own inquiry questions that align to the larger question by focusing on a specific area that is relevant and meaningful for them.

Surrounding the centre of the model are three frameworks that support learning (see diagram above): Circle Learning, Universal Design for Learning, and Formative Assessment.

The formative assessment used in these classrooms is built around six strategies: learning intentions, criteria, peer and self-assessment, descriptive feedback, questioning, and ownership. Each of these elements is woven as much as possible throughout each learning opportunity.

Circle learning has become a process for teachers to engage students in conversations that help them clarify meaning through the sharing of ideas and questioning. When teachers facilitate and coach those conversations by asking probing questions, students are able to make the connections that enable them to apply their thinking as they seek to answer the inquiry question. The concept is based on Faye Brownlie’s work with Literature Circles, and has expanded to include Information Circles and Numeracy Circles.

The formative assessment used in these classrooms is built around the Six Big Assessment for Learning (AFL) Strategies and B.C. Ministry of Education Performance Standards that are promoted through the Network of Performance Based Schools and the B.C. Ministry of Education. Based on the original work of Black & Wiliam, the strategies are: learning intentions, criteria, peer and self-assessment, descriptive feedback, questioning, and ownership. Each of these elements is woven as much as possible throughout each learning opportunity.

Our approach to Universal Design for Learning (Rose & Meyer) is derived from the implementation of UDL work by CAST (Center for Applied Special Technology) and David Edyburn. The principles of UDL remind us that our students have diverse learning needs, and help make it possible to value and support these differences. We use UDL guidelines to ensure that we have multiple ways to engage learners, to process learning, and to represent learning. Technology is used to support learning whenever possible and all students are respected as learners with potential.

Surrounding the model are three driving questions that teachers and students use to fuel their reflection: What’s working? What do we need to rethink? What’s next? These questions help teachers and students to engage in ongoing reflection that moves learning forward.

The Showcase

Paige Fisher

Several weeks later, the Grade 7 students come to the University to visit us. They bring along their completed inquiry projects so that we can host their learning showcase. All of the teacher education students are invited and they eagerly interact with the Grade 7 students as they talk about their completed inquiries. The celebration of learning that we witness is an example of the showcases that culminate each inquiry project. It is an opportunity for students to share their best examples of work and provides an authentic audience for their perspectives on how the inquiry has transformed their thoughts, actions, and beliefs. My hope is that there has also been a transformation of the thoughts and beliefs my students hold about what is possible in their future classrooms.

EN BREF – « C’est comme ça que j’apprendrai à partir de maintenant… Ça fonctionne vraiment pour moi! » – Le modèle de propulsion de l’apprentissage est fondé sur le concept de la communauté d’apprenants. Au début de l’année scolaire, les enseignants développent avec les élèves une vision des attributs requis pour assurer la réussite de chaque personne de la classe. Les élèves peuvent alors commencer à acquérir les compétences métacognitives qui les aideront à prendre en charge leur propre apprentissage. Cette culture de classe est nécessaire pour que le groupe puisse continuer d’utiliser les processus d’apprentissage énoncés tout au long du modèle – tournant autour de questions guidant l’élan d’apprentissage de chaque sujet. Ils commencent par l’élaboration d’une question globale fondée sur des concepts dérivés des résultats d’apprentissage provinciaux. Le but consiste à transformer la réflexion, les actions et les croyances des élèves à propos du sujet général. Une fois que les élèves ont acquis suffisamment de connaissances de base, chacun peut créer ses propres questions, alignées avec la question globale, en approfondissant un aspect précis qui lui est pertinent et significatif.