Guided Physical Play in Kindergarten

Building foundations for literacy and numeracy

Five-year-old Nancy is busy with clay. At first the chunk she pulls off is too hard to shape, but she’s learned to warm and knead it until it’s softer. She rolls it into a long cylinder and coils the tapering “bug” to attach to her leaf. Then she pulls off two larger bits of green clay to make more leaves for her growing tree. “Too big,” she mutters, and pulls them off again. She cuts one of the balls in half and tries again, this time using her fingers to spread the clay into a thin leaf shape perfect for her imaginary tree.

Play is often described as “the work of childhood.” While the idea of play eludes any single definition, the thread that unites various types of childhood play is pure and simple pleasure. It is its own reward and is self-reinforcing.

In this short article, we make a pitch for a greater focus on fine motor control through guided exploratory play in the Kindergarten program, emphasizing the importance of direct tactile experiences – handling and manipulating objects or materials in the real world in real time. This type of play fulfills several important goals of early childhood learning. First, body-object interaction (BOI) supports the development of stable, internalized models for learning the world: its shape, size, speed, distance, texture, structure, and whole-part relationships, for example. Concepts of shape and size are key to alphabet recognition and the type of reasoning that is foundational for early numeracy understandings in Grades 1 and 2.

Second, guided physical play promotes fine motor control. The Kindergarten years are the time to afford opportunities for play with tweezers, popsicle sticks, crayons, markers, and clothes pegs to strengthen the muscles and the neuropathways for the demands of written literacy, beginning just around the corner!

Finally, BOI develops the associated vocabulary as children learn to name and describe their interactions with the material world.1 Children with nimble fingers are found to have a larger developed lexicon of concrete objects, and interestingly, of more abstract concepts, too. Suggate and Stoeger suggest that “embodied cognition” enjoys a processing advantage, and that the connections between cognition, language and physical contact with the material world provide distinct benefits to youngsters who have had rich opportunities for these types of experiences in early life.

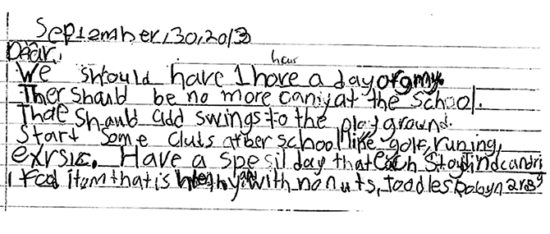

Figure 1: Writing Sample

We find plenty of evidence, however, that Canada’s young children are generally not sufficiently engaged in this type of play prior to their arrival in Kindergarten. The Early Development Instrument (EDI) analyzes Pan Canadian data on five-year-old children on five domains.2Outcomes indicate fewer than 50 percent of Canada’s young children are developing as they should along all five domains of early development. The ParticipACTION 2016 Report Card reports that only nine percent of Canada’s young children are getting the recommended amount of daily exercise, and increased numbers are not getting enough sleep.3 Our own work with Grade 2 children who are gifted revealed their overall lack of readiness for the demands of early written literacy learning, as noted in their distinct, belaboured printing efforts.4 (See Figure 1: Writing Sample.) Our intervention of explicit printing instruction using a programmatic, developmentally progressive approach can, we found, change the slope of the educational trajectory. However, remedial or “catch up” teaching is more difficult and time consuming than “just right teaching” might have been in the sensitive window of time in Kindergarten and Grade 1. Hence our motivation to focus on guided physical play at a much earlier stage in the educational experiences of young students.

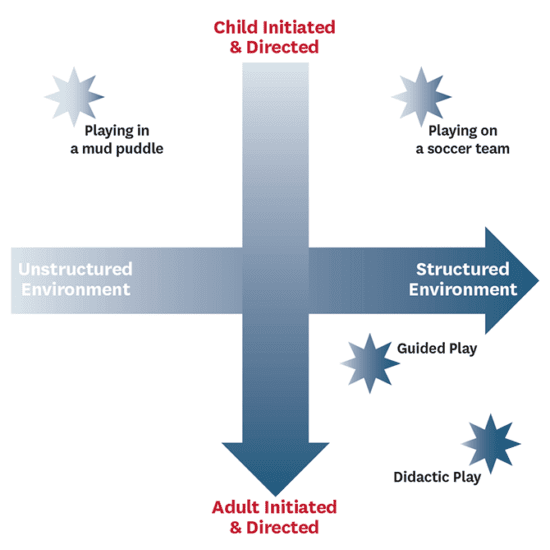

Figure 2: Matrix of Types of Play

We position various types of play by way of a framework we have organized around two continua: from child-initiated and directed to adult-initiated and directed; and from unstructured to structured play. (See Figure 2: Matrix of Types of Play.) We locate guided play in the mid-zone of the lower right quadrant, and define it as:

Purposefully designed activities and tasks that we think will be engaging and fun, are directed to some learning goal, and reflect a sense of pedagogical intent. Children’s motivation, curiosity, desire for mastery and their choices for how they interact with the materials are elements of the design. Children are actively involved in advancing embodied cognition and neuro-motor skills relevant and necessary to early language and literacy learning.

The research literature on play-based learning places a much heavier emphasis on inquiry, pretend, imaginative, discovery, fantasy, creative, and socio-dramatic play that is child driven, all types of play that would be located in the upper left quadrant. We advocate for a more balanced approach in the Kindergarten program.

Inspired by Montessori’s5 ideas about the role of the prepared environment and the importance of the materials children play and work with, we suggest the following 11 activities as a starting point to our colleagues in the field who might also be thinking of re-aligning their Kindergarten program. The possibilities are limited only by a teacher’s imagination, though!

- Blocks, bricks: Play with blocks and bricks promotes spatial reasoning as children develop concepts of size and shape, stability and structure.

- Lego pieces: Shapes that fit together and can be taken apart to create something new help to develop the concept of parts to a whole. Meanwhile, all that pushing together and pulling apart of little pieces develops fine motor skills and strong fingers. My friends who are architects and civil engineers say Lego was their favourite toy as children.

- Bits and pieces: Something as simple as a jar of buttons and a tray are enough for children to handle and sort for size, shape, colour, and then create sequences and patterns. As mentioned earlier, these foundational concepts developed through nimble fingers are crucial for numeracy and literacy learning.

- String and beads: Make a necklace! This can include making a pattern or sequence of coloured beads.

- Paper, scissors, crayons, markers, glue sticks, collage materials: Fold, cut, decorate, and print a simple message to make a card for Grandma’s birthday.

- Real-life objects: Using tweezers, clothes pegs, and chopsticks, children develop a good pincer grip through guided experiential play that simulates everyday tasks.

- Shared storybook reading: Books such as Rosie’s Walk (Hutchins, 1971) promote “languaging” around directional words, and imagining and drawing objects in space. Henry’s Map (Elliott, 2013) and Lucy in the City: A story about developing spatial thinking skills (Dillemuth, 2015) may serve as a bridge to learning activities that promote spatial reasoning through finger tracing and drawing maps.

- Play with clay: Kneading, molding and manipulating plasticine clay gives little fingers a great workout! Can they shape their ball of plasticine into an object that will float in a tub of water? Children delight in trying various shapes, with those “ahead of the curve” figuring out that weight and shape both play a role in whether the object will float.

- Origami for kids: folding and creasing, concepts of pattern, symmetry, sequence. There are dozens of simple projects for children to do: flowers, frogs, airplanes… the list is extensive.

- What’s in the bag? Fill a bag with “mystery” objects. Children take turns reaching in, focusing on one object, and describing the object by size, shape, structure, texture, what it might be used for, etc. for the class. Who’s the first to get it right?

- Slime! A current craze among kids is making and playing with magic slime. It is made with just a few easy-to-obtain ingredients, such as glitter glue and powdered fibre supplement. This strengthens small fingers. It also teaches procedural language and provides a simple chemistry lesson.

The human hand is complex and versatile – elegantly and exquisitely unparalleled in design to do the work of gripping, grabbing, holding, folding, pushing, pulling, punching, kneading, threading, stacking, rolling, throwing, squeezing and squishing.6Through our sense of touch and our tactile connection to the world, we learn the world and engage with it, constructing the stable internal models that are necessary for numeracy and literacy development. These experiences need to be mediated through elaborative and collaborative talk between adult and children. As educators, we are responsible for preparing children for literacy and numeracy learning by engaging little fingers in guided play that lies at the intersection of cognitive, linguistic and neuro-motor integration: embodied cognition. Guided play can make this mandate fun, exciting and productive.

We want to know what you think. Join the conversation @EdCanPub #EdCan!

Photo: iStock

First published in Education Canada, March 2018

1 Sebastian Suggate and Heidrun Stoeger, “Do Nimble Hands Make for Nimble Lexicons? Fine motor skills predict vocabulary of embodied vocabulary items,” First Language 34, no. 3 (2014): 244-261. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0142723714535768

2 Magdalena Janus and Caroline Reid-Westoby, “Monitoring the Development of all Children: The Early Development Instrument,” Early Childhood Matters 125 (2016): 40-46.

3 ParticipACTION Canada, “Are Canadian Kids too Tired to Move?” The ParticipACTION Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth (2016). https://www.participaction.com/sites/default/files/downloads/2016%20ParticipACTION%20Report%20Card%20-%20Full%20Report.pdf

4 Hetty Roessingh and Michelle Bence, “Intervening in Early Written Literacy Development for Gifted Children in Grade 2: Insights from an action research project,” Journal for the Education of the Gifted 40, no. 2 (2017): 168-196. http://journals.sagepub.com/eprint/Qh7ZS5zKKStQgesK4ibZ/full

5 Angeline Lillard, “Playful Learning and Montessori Education,” American Journal of Play 5, no.2 (2013): 157-186. www.journalofplay.org/sites/www.journalofplay.org/files/pdf-articles/5-2-article-play-learning-and-montessori-education_0.pdf

6 Jerry Bergman, “The Human Hand: Perfectly designed,” Creation Research Society Quarterly 50 (2013): 25-30. www.creationresearch.org/members-only/crsq/50/50_1/CRSQ%20Summer%202013%20Bergman.pdf