The Importance of Followership in Schools: First, Teacher Awareness

Many books have been written about various leadership characteristics, styles, outcomes, and purposes in schools. Much less has been written about followership. But, in order to have leaders, we must have followers. Leadership is the act of motivating a group of people to move towards achieving a common goal. Followership is the act or condition of following a leader. As a former long-time school and district administrator, I would like to draw attention to the issue of followership.

Robert Kelly is an early pioneer of followership and the author of The Power of Followership; his thoughts provide a framework for this brief discussion.[1] A healthy, effective school environment involves a dynamic between teachers, students, school administrators, parents, and support staff. I suggest that, as central players in this dynamic, teachers are both leaders and followers in their classrooms, schools, and learning communities.[2] Greenleaf, who coined the term servant-leadership (a moral, service-first approach to leadership), wrote about the importance of effective followers.

They express in different ways my wish that leaders will bend their efforts to serve with skill, understanding, and spirit, and that followers will be responsive only to able servants who would lead them – but they will respond. Discriminating and determined servants as followers are as important as servant leaders, and everyone, from time to time, may be in both roles.[3]

We must understand the functions of both leadership and followership in our schools and realize that the motivation of followers will have an impact on the effectiveness of the school and specifically on the organizational leadership.

Followership Styles in Schools

Although schools are about learning, development, values, and ethos, I suggest all of these components are really about relationships. Authentic relationships require work to build, strengthen, and maintain. This is an ongoing and constant issue that must be a priority if a sense of inclusivity, respect, collaboration, transparency, and caring is to be developed and valued in schools.

Kelly describes seven follower paths that help us understand the role each member of the school team plays in the leadership-followership relationship: apprentice, disciple, mentee, comrade, loyalist, dreamer, and lifeway.[4] With the move toward democratization in our schools and the use of school teams to develop policy, curriculum, school plans, and school celebrations, the relationship between team leaders and followers has become critical in achieving planned goals and outcomes.

With the move toward democratization in our schools … the relationship between team leaders and followers has become critical in achieving planned goals and outcomes.

If we relate Kelly’s seven followership paths to the internal school personnel groupings, we see that in most schools, the principal is the master-leader, and often a first-time vice-principal is his or her follower or apprentice, learning how to be a strong leader by following the principal’s example. Today, many vice-principals choose to remain in their role. They, like many of their teacher-colleagues, are comfortable with themselves and in their roles, and just want to contribute to the school goals. These disciples can carry the message of a particular school culture and represent the ideas of the formal leader (principal). There are certain rules that all school staff follow – for example, related to issues of safety. I suggest that, in these situations, all staff act as disciples.

There are other teachers who want to change themselves through personal growth (mentees). Each year teachers develop a personal growth plan, and study or develop a new skill to strengthen their teaching in the classroom. New teachers often are assigned a mentor to guide them and act as a resource, especially during their first year in a classroom; others use a mentorship model to achieve interpersonal and intrapersonal goals; some aspire to lead. Mentorship is closely related to apprenticeship, which is directed toward mastery of specific skills – as in the case of the vice-principal.

Comrades are happiest expressing their followership by bonding with others in situations where many talents are needed to accomplish a goal, such as in a curriculum development committee.

Loyalists can have a particularly powerful impact on the success of a leader. A school principal may have a broad following that contributes to his or her success – or vice versa. Loss of loyalty can contribute to an unpopular or ineffective principal’s demise.

Dreamers follow their own ideas, their guiding force, not necessarily those of the leader. Such staff are “outside the box” and may “do their own thing”.

The last of Kelly’s followership paths is that of the lifeway; this person is convinced that the chosen path of service or helping others provides the best or most satisfying way of living.

Lifeways and Servant-Leadership

Kelly directly links the lifeways path to Robert K. Greenleaf’s philosophy of servant-leadership, an ethical-moral, transformational form of leadership-followership-service:

The servant-leader is servant first. It begins with the natural feeling that one wants to serve. Then conscious choice brings one to aspire to lead. The best test is: do those served grow as persons; do they, while being served, become healthier, wiser, freer, more autonomous, more likely themselves to become servants?[5]

Greenleaf suggests that we are actually on a continuum during our lifetime.[6] At one end of the continuum is leadership and at the other end is followership. We move back and forth along this continuum and neither one nor the other is better. It is only when we stop moving along the continuum that we stop growing and learning, and become stagnant. Thus, if a school is truly developing and growing, and if learning is collaborative, each person is leader and follower at various times. “Even the ablest leaders will do well to be aware that there are times and places in which they should follow.”[7]

If a school is truly developing and growing, and if learning is collaborative, each person is leader and follower at various times.

Let me share this example. Many years ago, when I was principal in a K-5 school, the computers went down across the school on a Monday morning. The technical support teacher was absent. No one else on staff was able to help. Out of complete desperation, I went to the Grade 5 classroom and asked who knew a lot about computers and three boys stood up. I then asked which one of them knew the most. Two of the boys turned and looked at the same boy. I then explained the situation. This student then went room to room, and by morning recess all the computers in the school were up and running. I was the follower and this student was definitely the leader in that situation.

Perhaps by understanding the motivation of the various follower paths, administrators, team leaders, and general school personnel could develop greater understanding and improved interpersonal connections within a school community.

Where are you now?

A simple dialogue between colleagues can reveal personal preferences for circumstances that encourage either leadership or followership and an appreciation for individual and group strengths and weaknesses. The question is, “Where are you now?”

In response to school administrator and school superintendent requests, I initiated a journey of self-discovery within an individual school staff of 35, and later with a school district of 410 teachers and principals, with the following questions:

- What is your greatest strength?

- How have you used this strength in your daily life?

- What is your greatest area of weakness?

- How has the weakness caused you problems in the past?

- Describe a situation where you were leader.

- Describe a situation where you were follower.

- Have you a preference? Leadership or followership? Explain your choice.

- Describe a situation where you relied upon your moral and/or ethical leadership to deal with a difficult decision?

- How do you prepare to make a decision?

- How do you react if the decision turns out to be wrong?

This process provided participants with early steps to learning about each other; to building stronger teams; to understanding the strengths within the group; and to understanding themselves and their values. It is useful for all school staff to become aware of the various ages and stages, strengths, challenges, and values of the members of their group, and working with school staff in this way may provide occasion for the identification of the seven types of follower paths and related motivations. Such opportunities can strengthen the connections that bind a school together. The opportunities for school members to participate in the ebb and flow of shared information, and to develop greater understanding and appreciation for each other as leaders and followers, will reinforce an atmosphere of transparency, trust, and authenticity. A small sample of the feedback from the previous self-discovery questions included:

- A good leader must be a good follower and a good listener.

- Use your strengths to help rectify your weaknesses.

- Introduce students to leadership-followership roles in the classroom. Talk about them. How do they feel as a leader? How do they feel as a follower?

- Leaders and followers are both part of the whole puzzle that makes up our school.

- I can be myself and I have lots to offer my school community.

- The roles of leaders and followers constantly change.

- I must continually remind myself of students being on a continuum at the same time as I am.

Such responses seem to support the investment of time in such activities.

Followership Questionnaires

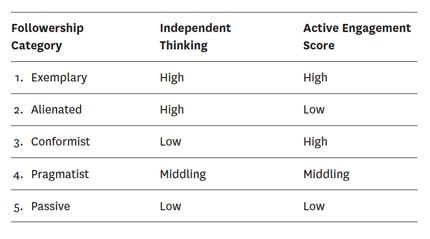

Kelly has developed a Followership Questionnaire to help people determine the kind of follower they are and to identify their strengths and areas that need improvement.[8] Independent thinking and actively carrying out one’s role were identified as critical to followership. Briefly, Kelly identified five categories of followership, and assigned each a score for independence and active engagement.

It seems to me that understanding the leadership-followership dynamic that exists in the school may promote inclusivity, transparent interaction, and authenticity for all members of the school community. Such clarity helps to develop trust and loyalty. If the relationships within the school are authentic, then the school community will also be authentic, there will be honesty and openness, and a sense of trust and safety will prevail. Wheatley compares these relationships to a spider’s web:

Most of us have had the experience of touching a spider web, feeling its resiliency, noticing how slight pressure in one area jiggles the entire web. If a web breaks and needs repair, the spider doesn‘t cut out a piece, terminate it, or tear the entire web apart and reorganize it. She reweaves it, using the silken relationships that are already there, creating stronger connections across the weakened spaces.[9]

Conclusion

Kelly emphasizes the importance a leadership-followership balance in healthy, democratic schools, where webs of relationships are developed by reaching out to each other; by trying to understand and be true to ourselves (authentic); and by trying to understand and appreciate one another. These same understandings can be applied to children in the classroom. Educators must become students of their students.

Effective leaders, says Kelly, are people who “have the vision to set corporate goals and strategies, the interpersonal skills to deliver consensus, the verbal capacity to communicate enthusiasm to large and diverse groups, the organizational talent to coordinate disparate efforts, and above all, the desire to lead.”

Effective followers “have the vision to see the forest and the trees, the social capacity to work well with others, the strength of character to flourish without heroic status, the moral and psychological balance to pursue personal and corporate goals, and above all, the desire to participate in team effort for the accomplishment of some greater common purpose.”[10]

We need both in our schools.

EN BREF – De nombreux livres traitent des différents styles, caractéristiques, résultats et finalités du leadership dans les écoles. On a beaucoup moins écrit sur le suivisme. Or, pour qu’il y ait des leaders, il doit y avoir des suiveurs. Comprendre la dynamique leadership-suivisme d’une école peut donc promouvoir l’inclusivité, l’interaction transparente et l’authenticité pour tous les membres de la communauté scolaire. Cette clarté contribue à développer la confiance et la loyauté. Robert Kelly décrit sept voies de suivisme qui contribuent à comprendre le rôle que joue chaque membre de l’équipe-école dans les rapports leadership-suivisme : apprenti, disciple, protégé, camarade, loyaliste, rêveur et mode de vie. Compte tenu du virage vers la démocratisation des écoles et du recours aux équipes-écoles pour développer des politiques, des curriculums, des plans d’écoles et des célébrations scolaires, les rapports entre les leaders et les suiveurs d’une équipe sont devenus critiques pour réaliser les objectifs et les résultats visés.

[1] Robert Kelly, The Power of Followership: How to Create Leaders People Want to Follow and Followers who Lead Themselves (New York: Doubleday Currency, 1992).

[2] Carolyn Crippen, “Serve, Teach, and Lead: It’s all about Relationships,” Insight: A Journal of Scholarly Teaching 5 (2010): 27-36.

[3] Robert K. Greenleaf, Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness (Mahwah: Paulist Press, 1977): 3-4.

[4] Robert Kelly, “In Praise of Followers,” Harvard Business Review (November, 1988): 51.

[5] Robert K Greenleaf, The Servant as Leader (Indianapolis: The Robert K. Greenleaf Center, 1970), 7.

[6] Greenleaf, 1977.

[7] Larry Spears, ed., The Power of Servant-leadership: Essays by Robert K. Greenleaf (San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc., 1998): 114.

[8] Kelly, 90-97.

[9] Margaret Wheatley, Leadership and the New Science: Discovering Order in a Chaotic World (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc., 2006), 145.

[10] Kelly, 1998, 142.