Language “By Hand”

Why printing and spelling are important to early literacy learning

THE END OF GRADE 2 and early Grade 3 are recognized as important milestones in young learners’ written literacy development. At this juncture, children are expected to have “language by hand” under sufficient control to participate in an array of literacy demands, increasingly for school-related work and the transition to academic literacy.

THE END OF GRADE 2 and early Grade 3 are recognized as important milestones in young learners’ written literacy development. At this juncture, children are expected to have “language by hand” under sufficient control to participate in an array of literacy demands, increasingly for school-related work and the transition to academic literacy. This includes both printing and spelling, generally described as the transcription elements of early literacy achievement.[i]

Neuroscience research can inform our instructional approaches to helping young learners gain control over early written literacy. Specifically, it illuminates the role of automaticity in relation to working memory; I also discuss the importance of kinesthetic or embodied “knowing” as a consequence of printing; and finally the importance of pre-writing activities, especially drawing and colouring, as these influence a young learner’s ability produce quality text by the end of Grade 2 or early Grade 3.

The human brain: Lessons from the neurosciences

Research in neuroscience over the past 25 years has produced invaluable insights into the interplay between the neuromotor, the cognitive and the linguistic systems. The footprints of children’s written literacy development are imprinted on their neurocircuitry and are visible in their written efforts.

For children to successfully convey their thoughts and ideas via print mode, they must have firm control over printing and spelling. Printing and spelling must come automatically – almost unconsciously or effortlessly. Only then can sufficient working memory space be made available to generate thoughts and encode them in just the right words at the right time for the task at hand. Too many competing demands on working memory places constraints on this cognitive real estate – it is scarce as well as fleeting, especially among young learners. In short, the brain cannot multi-task.[ii] By off-loading printing and spelling – the transcription skills – young authors can allocate working memory space to finding words and other elements of conveying meaning.

The physical act of printing engages the neuromotor system, leaving behind neural pathways that, with practice, become ingrained over time.[iii] There is a difference between printing the letter ‘d’ and touching it on a keyboard. Children who first learn to print transfer this skill more readily both to letter recognition, a key element of spelling, and to keyboarding.[iv]

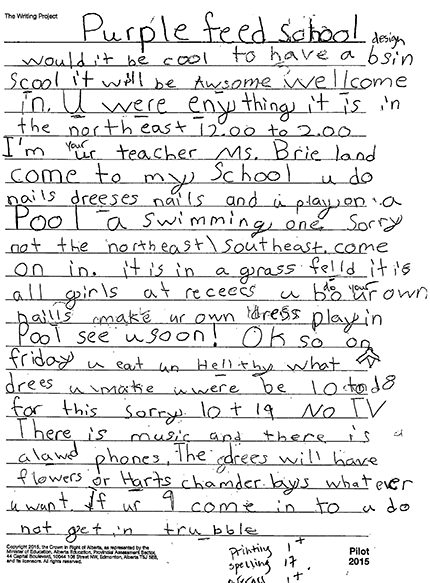

Figure 1 reflects the belaboured efforts of a young learner in the early part of Grade 3. For this assignment, students were asked to describe their ideal school. This youngster has average word knowledge as measured by a standard vocabulary test. Imagine the frustration of having to over-focus on the sheer physical demands of printing, leaving no working memory resources available for organizing and connecting ideas. In 143 words (87 percent correct spelling), several fragmented ideas are suggested about a design school. Common spelling patterns and sight words are inconsistently produced: dress, nails, school, welcome. Reversals are evident – design, do – as is unevenness in letter shape, size and spacing. Better control over language by hand would give this young author the opportunity to maintain topic control, offer details, retrieve vocabulary and develop ideas more fully.

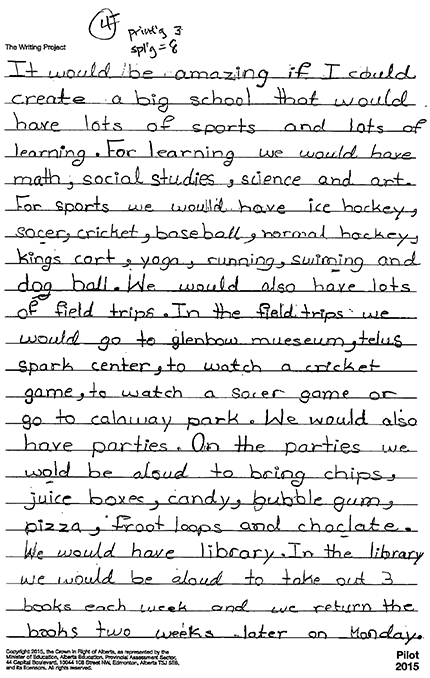

Figure 2 was written to the same prompt in early Grade 3 by a student with average word knowledge – about the same as that of the author of the sample in Figure 1, also matched for age. The second sample reflects good control over the demands of printing and spelling (98 percent correct in 248 words on the page). The number of words is taken as a proxy for fluency in early writing, a key contributor to overall quality of writing at this stage. The writer opens and closes appropriately and develops the idea of a school for sports and learning. Vocabulary use includes rare words such as create, museum and creatures.

In early literacy development, all young authors deploy the high-frequency words in their oral repertoire. The use of more sophisticated vocabulary choices is an important emerging feature of Grade 3 writing, as control over printing and spelling are assumed.

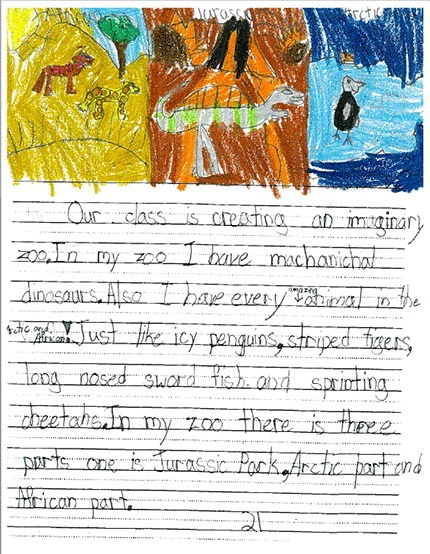

For a young writer in the early stages of literacy development, it is a long, long way from encoding thought into words, to the neuromotor demands of printing. Colouring, drawing and various “brainstorming” tasks such as semantic webbing serve multiple purposes in this journey. These activities may lessen anxiety about the writing task to come. Drawing may help in retrieving key vocabulary – a type of lexical priming activity. And webbing can display connections and relationships, holding them steady as an external memory support for the writing.

Figure 3 below illustrates the effective use of drawing and colouring as a pre-writing task. Note the clear connection between the two elements in the writing process.

Reframing literacy learning

Printing and spelling are often associated with memory work, copying, drill, mindless and decontextualized repetition from lists, and bored youngsters. It need not be so. Far from being a mechanistic exercise, both printing and spelling require the active engagement of the neuromotor, linguistic and cognitive systems. Spelling is essentially a pattern-seeking endeavour – a type of puzzle that unlocks the meaning of words: rowed, road and rode are not interchangeable. Once children “crack the code” and make these connections, their efforts can be allocated to finding just the right word at the right time to express their thoughts. In my experience, young children enjoy “puzzling”– looking for patterns – and take pride in mastering something, including printing and spelling.

There are short cuts to realizing good achievement outcomes in early literacy learning. Achieving an acceptable “hand” that is both legible and fluent enough to allow the writer to allocate attention to the other demands of text generation does not have to take a lot of time. A recent study undertaken in the Calgary Board of Education suggests that direct and consistent instruction of about 20 minutes a day for 40 consecutive days can have a tangible impact on the quality of children’s printing.[v] With instructed support, 95 percent of young children are capable of legible printing by the end of Grade 2.[vi] From a neuromotor perspective, the sensitive window of time to introduce printing is the second half of Grade 1. At this young age, it is important to be mindful of the range of developmental readiness there may be within a single class setting: it is easily possible to have an age range up to 18 months.

Adopting developmentally appropriate practices and differentiating printing instruction is necessary to avoid frustrating or overwhelming those who are still developmentally “young” for their grade placement. Parents have various reasons for choosing when to place their child in school: “hold-backs” may be sensitive to their child needing time to mature, since a gap of 18 months represents an enormous slice of a child’s life in the beginning years of their schooling, when both cognitive and linguistic growth occur rapidly.

There is good news for young writers who either did not receive instruction in the early years, or who continue to struggle with language by hand into the upper elementary grades. Even at this age, good results can still be realized for these students.

Similarly, a developmentally progressive approach to teaching letter recognition and spelling patterns can have distinct and positive results.[vii] At the end of Grade 2, look for 85 percent accuracy in spelling; and by the end of Grade 3, 95 percent accuracy in spelling. In a study Susan Elgie and I conducted,[viii] a key finding was the correlation between printing, spelling and the number of words on the page with overall quality writing standard in late Grade 2/early Grade 3, findings that reinforce those of others in the research community cited in this article.

Room for improvement!

Research, outcomes from formative assessment data shared with me, work in the field with classroom practitioners and my work with large sample sizes of children’s writing is telling: our young learners are not achieving as they might in their early written literacy development.

Teachers can benefit from an array of professional development opportunities, including workshops and involvement in school-based Professional Learning Communities that focus on early literacy teaching and learning. A more systematic approach to studying assessment data can also inform instructional practices.

Teachers need to know not only what to teach, but why what they do is important and how it contributes to children’s literacy development. Connecting the dots between research and practice can lead to a more informed instructional stance, and in turn, enhanced outcomes for our young learners.

6 ideas for improving early literacy outcomes

1. Direct and explicit instruction: Printing and spelling must be taught directly. A three-step progression – I do, we do, you do – is advocated. While commercially prepared materials and programs are available, web-based resources are also available. Teachers should choose and implement what works for them.

2. Mindful, effortful practice: Printing and spelling involve cognitive and neuromotor learning that needs to be practiced. Teacher encouragement and feedback are the key.

3. Consistency and making time: Short periods of time – 20 minutes a day – is recommended. Children can only focus for so long. Consistency in program choice within a grade team, and across grades is also important. Schools are encouraged to adopt a programmatic approach so that children hear the same language and practices throughout the K – 3 years.

4. Developmentally appropriate and progressive teaching: Each stage of printing and spelling achievement builds on what came before, and entails a certain amount of “readiness.” While the second half of Grade 1 is recognized as a major threshold point for printing, many occasions for literacy engagement would have come before: colouring, scribbling, and drawing are all ways that children learn to represent their thoughts before they have the fine motor abilities for printing. In the earlier stages, playing with building blocks, playdough and other activities that build finger strength and dexterity are important.

5. A process approach to writing that includes drawing and colouring before the writing task: Upon completing their writing, children can be asked to reflect on something they did well and like about their writing, and something they could work more on.

6. Continued focus on vocabulary teaching and learning, starting at a young age: While all children become literate with a relatively small vocabulary, those youngsters who demonstrate excellent writing are using more sophisticated and rarer words to convey their thoughts with precision and efficiency. Linguistically vulnerable children, for example, children raised in poverty and those who are immersed in another language at home, may benefit from enriched experiences at school.

First published in Education Canada, September 2016

[i] M. Joshi, R. Treiman, S. Carreker, and L. Moats, “How Words Cast their Spell: Spelling is an integral part of learning the language, not a matter of memorization,” American Educator (Winter 2008/09): 6-8, www.aft.org/pdfs/americaneducator/winter0809/joshi.pdf

[ii] Jon Hamilton, “Think You’re Multi-tasking? Think again,” Transcript from Morning Show (NPR Radio: 2008).

www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=95256794

[iii] Gwendolyn Bounds, “How Handwriting Trains the Brain,” Wall Street Journal (October 5, 2010).

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704631504575531932754922518.html

[iv] Maria Konnikova, “What’s Lost as Handwriting Fades?” New York Times (June 2, 2014). www.nytimes.com/2014/06/03/science/whats-lost-as-handwriting-fades.html?_r=0

[v] G. Roberts, A. Derkach-Ferguson, J. Siever and M. Rose, “An Examination of the Effectiveness of Handwriting Without Tears® Instruction,” Journal of Occupational Therapy 8, no.2 (2014): 102-113.

[vi] Hetty Roessingh and Susan Elgie, “From Thought, to Words, to Print: Early literacy development in Grade 2,” Alberta Journal of Educational Research 60, no. 3 (2014): 576-597.

http://ajer.journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/ajer/article/view/1508/pdf_16

[vii] Ken Stahl, “New Insights About Letter Learning,” The Reading Teacher 68, no. 4 (2014/15): 261-65.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/trtr.2014.68.issue-4/issuetoc

[viii] Roessingh and Elgie, “From Thought, to Words, to Print.”