Duty to Report

What every teacher should know about reporting child abuse

Teachers are in a unique position to notice that child abuse may be occurring due to the extensive amount of time that they spend with their students. Yet teachers are often not adequately prepared by their school boards on issues relating to detecting and reporting child abuse.1 This article provides essential information regarding a teacher’s duty to report children in need of protection, including: when teachers are required to report child abuse, common legal questions, signs and indicators of abuse, how to respond to disclosures of abuse, how to make a report, and what happens after a report is made. Teachers should also refer to their board’s specific policy on reporting children in need of protection. If you suspect that a child might be in need of protection, contact your local Children’s Aid Society.

The requirement to report

Everyone is legally required to report when they suspect child abuse has occurred. No province or territory requires the person who suspects abuse to collect evidence to support their claim.

Signs and indicators of abuse

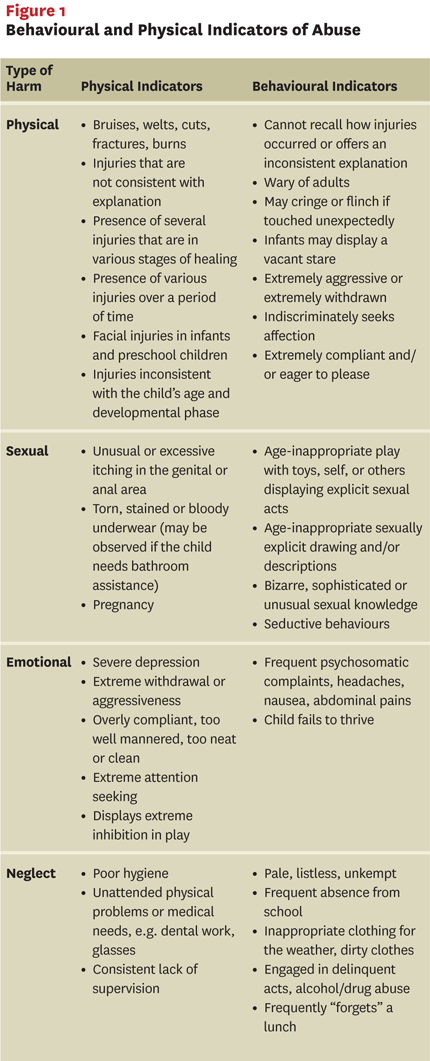

Figure 1 (see below) provides a list of common physical and behavioural indicators of abuse. Recognition of child abuse is not normally based upon the detection of one or two indicators, but rather relies on the recognition of several indicators over a period of time. It is important to remember that some indicators, both physical and behavioural, may be the result of something other than abuse.

Keeping records

Keep a journal that contains observations of your students, including observations of unusual behaviour or worrisome physical symptoms. Keeping records serves two purposes. First, your notes over time may provide enough information to warrant you to suspect that a child may be in need of protection. Second, this information can be subpoenaed in court if a case arises. Therefore, records must only contain facts, observations, and direct conversations with the child. In addition, each entry should be dated and signed.

What if you are unsure?

If you are unsure that abuse has occurred, you have three options:

1. Consult colleagues. Get support and advice from your colleagues and supervisors. Compare notes and brainstorm possible strategies.

2. Call the local Children’s Aid Society. An intake worker at the Society will listen to your concerns. At this point you do not have to provide your name or the name of the child. The intake worker will let you know if your concerns warrant opening a case. If the intake worker believes there is suspected abuse, you will be asked to provide identifying information on the child and yourself.

3. Speak with the child. Use open-ended questions, for instance, “How did you get that bruise?” It is critical that you do not use leading questions or probe for answers. Child abuse cases can be dismissed in court if it is felt that the initial interviewers biased the children. Be aware that asking questions may result in the child disclosing abuse has occurred.

When a child discloses

It is essential for teachers to understand how to properly respond to students who have disclosed they were abused. If a student discloses abuse to you:

Stay calm and listen. Let the child tell his or her story. The child needs to know that it is okay to talk about what happened. If a disclosure is made during class time, have someone relieve you of your class duties so that you can continue talking with the student privately.

Go slowly. Let the child tell you what happened in his or her own way. Record what the child says verbatim. Do not adjust the child’s use of language.

Be supportive. Let children who confide in you know that:

- They are not in trouble and have not done anything wrong;

- You believe them and they did the right thing by telling you;

- They are not to blame for what happened;

- You will do everything you can to help;

- You know other people who can help them.

Don’t probe for details. It is sufficient to get only general information or the basic facts. The child will have to tell his or her story to a child protection worker, and potentially the police.

Explain to the child what will happen next. Let the child know you will need to report the abuse or neglect, and that you will be talking to a child protection worker who may need to come and talk to the child.

Be honest. If the child asks questions, answer what you can. If you do not know the answer, it’s okay to say, “I don’t know.”

Do not make promises you cannot keep. Don’t promise to keep the abuse or neglect a secret.

How to report suspected abuse

1. Make notes; date and sign your entry.

2. Locate your school board’s policy or procedure on reporting suspected child abuse. Some boards have reports that must be filled out when a call is made to a Children’s Aid Society.

3. Inform your principal that you will be making a report. If the principal is not available, continue on with the reporting process and contact the principal as soon as reasonably possible.

4. Call the local Children’s Aid Society. You will need to provide the following information to the intake worker:

- Child’s name, age, gender, address, and names and ages of any siblings who live with the child;

- Parent’s name and address;

- Nature and extent of the injury or condition observed;

- Prior injuries/suspicions and when observed;

- Actions taken by the reporter (e.g. talking with the child);

- Where the act occurred;

- Your name, location, and contact information (your name will not be given to the parents; however, the caseworker will say the report came from the child’s school).

There are also questions you should ask the intake worker:

- If a case will be opened;

- If someone will be coming to the school to interview the child;

- Who is responsible for contacting the parents;

- When updates on the case will be provided;

- Any other questions you may have.

What happens next?

There are several possible scenarios that may occur after a report is made. First, the Children’s Aid Society (CAS) must either reject or accept the case. The report will be rejected if the victim is not considered a “child” under provincial legislation. The report will also be rejected if it is determined that the allegation does not meet the standard for abuse or neglect.

If CAS determines the report meets the requirements for an investigation, CAS will assign a social worker to the case. The social worker has 60 days to investigate and reach a finding. Most calls that require further investigation fall into two categories – those that must be responded to within 12 hours, and those that must be followed up within seven days. The level of risk for the child involved determines the response times. If the child is deemed to be in immediate danger of being further abused, the child will be removed from his or her home. However, it is the goal of CAS to keep families together. In 92 percent of investigations, the child will remain with his or her family.2 If there is a high risk of further abuse, the family may be required to participate in court-mandated services. If it is deemed that there is little chance of further abuse, CAS may suggest that the family participate in voluntary, preventative services. The investigation may also result in no credible evidence of abuse or neglect being found. In this situation, the case may be closed, or the family may choose to voluntarily enroll in preventative services offered by CAS.

Common legal questions about reporting abuse

Can I be held civilly liable by the child’s guardians if I make a report but the investigation reveals there was no abuse?

No, as long as the report was made in good faith, you cannot be sued.

What happens if I fail to make a report of suspected abuse?

You may be convicted of an offence for failing to report suspected abuse. Depending on the province, you may face anywhere from $250 – $50,000 fine and up to 24 months imprisonment. Moreover, you may face professional misconduct charges from your professional organization.

En Bref – En raison de la grande quantité de temps qu’ils passent avec leurs élèves, les enseignants se trouvent dans une position unique pour remarquer les signes possibles de maltraitance. Pourtant, les enseignants ne sont pas bien préparés par leurs conseils scolaires, en ce qui concerne très souvent les questions relatives à la détection et au signalement d’abus des enfants. Cet article fournit des informations essentielles concernant le devoir d’un enseignant de signaler les enfants ayant besoin de protection, notamment les cas où les enseignants sont tenus de signaler la maltraitance des enfants, les questions juridiques courantes, les signes et indicateurs d’abus, les manières de répondre aux divulgations d’abus, la rédaction d’un rapport et ce qui arrive après la transmission d’un rapport.

Photo: Milan Markovic (istock)

First published in Education Canada, September 2015

1 Samantha Shewchuk, “Children in Need of Protection: Reporting policies in Ontario school boards,” Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy 162 (2014).

2 Nico Trocmé, B. Fallon, B. MacLaurin, V. Sinha, T. Black, E. Fast, C. Felstiner, S. Hélie, D. Turcotte, P. Weightman, J. Douglas, and J. Holroyd, Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect 2008: Major findings (Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada, 2010), 2-3.