Boys Do Cry

Why conversations about gender are crucial in schools

As a young boy, I never quite fit the mould for masculinity placed before me. Singing the latest Spice Girls songs and playing with my Furby came naturally to me, as did exuberantly expressing my various emotions. As a result, I was sometimes deemed “too sensitive” or “soft.”

While I never questioned my gender identity, I still felt that my own way of expressing my masculinity was unique and different. Due to this, I faced ostracism and shame for my interests and emotional expressivity, and experienced continual gender policing and surveillance from both teachers and other students throughout my years at school.

The effects of various instances of gender policing still haunt my subconscious to this day. Experiences of being told, “Boys don’t sing and dance,” “Boys don’t cry,” and “Boys don’t run like that” repeated themselves throughout my formative years. I frequently flung my wrists around – this still hasn’t changed – but this form of effeminate behaviour received much criticism and commentary from my classmates. Other students often told me that I was “girly,” that the way I walked was for sissies; even my musical and artistic tastes were denigrated. Moreover, I was continually told to not be quite so “sensitive” by my teachers as I fought to rationalize my feelings. In short, I was deemed, to use the words of writers Ivan Coyote and Rae Spoon, a gender failure.1

When I decided to come out as gay at age 20, I thought I’d be entering a queer community that would embrace my effeminate and effervescent nature. Instead, I encountered a community that has elements of heavy hyper-masculinization in both embodiment and emotional detachment.2 While I eventually made wonderful gay male friends and learned to manoeuver through the ins and outs of gay male culture, it appeared to me that even in the community where I anticipated acceptance, I often found pressures to conform to masculinized expectations that did not match my own personality and sense of self.

Theorists have attributed these pressures to growing up in a society that invalidates visible gender nonconformity in childhood while upholding heterosexual masculinity as the ideal.3 Thus, cultural lessons about gender expression begin in early childhood, and conversations about gender at a young age are key to creating safer spaces for children to develop their gendered selves naturally and authentically.

Why talk about gender?

From a very early age, the gender expression of students is commonly policed by peers, teachers, and even parents.

As an educator who has worked with children and youth of all ages throughout my career, I see how gender is a foundational piece of a child’s identity and sense of self. Children experience a tremendous amount of societal pressure to conform to gendered ideologies. Whether inhibiting which articles of clothing are worn, refraining from crying or expressing emotions, or choosing not to engage in certain sporting and/or extracurricular activities, gendered behaviour is embedded within the social fabrics of the lives of children.

Within my own writings on gender and sexuality in schooling, I have tried to explore the ways in which we police and regulate genders and sexualities in school climates4 and argued that schools can and should be more gender transformative spaces for students. Why is this important?

We need more nuanced analyses of boys’ achievement in schooling that take into consideration factors of race, socioeconomic status and sexuality, along with the ability to comprehend which specific boys struggle in schools and how to engage in culturally relevant teaching.5

Boys who present themselves as effeminate are often (and often mistakenly) presumed to be gay. The stigma around gender nonconformity is often related to homophobia, while homophobia perpetuates the policing of students who are presumed to be gay.6

A school focus on gender as a social construct and fluid spectrum (rather than dichotomized sex) can break the binary that is often instilled between male and female, and foster understanding of the ways in which students have their gender expression policed and regulated.7

Children are frequently heterosexualized and subjected to rigid gender norms based on the desire to ensure heterosexuality as an “outcome” and norm. Moreover, products and media marketed towards children, such as Disney films, often propagate heterosexualized love storylines with idealized forms of masculinities and femininities embodied in the main characters.8

What to do?

Based on my own experiences as an effeminate boy in the school system, teachers need to take better notice of incidents of gender policing in schools and actively engage with their students in open and critical conversations about gender to question preconceived notions.

From a very early age, the gender expression of students is commonly policed by peers, teachers, and even parents. It is important that teachers create safer classroom climates by affirming students’ gender expression and identities (including checking students’ preferred pronouns on a regular basis and using gender neutral phrases to refer to groups of students). Dialogue about how gender is embedded within our social relations in schools and educator self-reflection are essential starting points for creating safer school climates for students to express themselves.

We want to know what you think. Join the conversation @EdCanPub #EdCan!

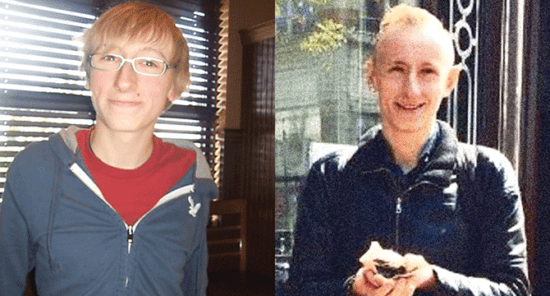

Photos: courtesy Adam William John Davies

First published in Education Canada, March 2018

1 Ivan E. Coyote and Rae Spoon, Gender Failure (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2014).

2 Francisco J. Sánchez, J. S. Westefeld, W. M. Liu, and E. Vilain, “Masculine Gender Role Conflict and Negative Feelings About Being Gay,” Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 41, no. 2 (2010): 104-111; Jeremy Alexander, “Fellow Gay Men, Stop Glorifying Toxic Ideals of Masculinity,” Huffington Post (November 22, 2016), www.huffingtonpost.ca/jeremy-alexander93/lgbtq-bro-%20culture_b_13154426.html

3 Alan Downs, The Velvet Rage: Overcoming the pain of growing up gay in a straight man’s world (Da Capo Lifelong Books, 2012).

4 Adam W. J. Davies, Evan Vipond, and Ariana King. “Gender Binary Washrooms as a Means of Gender Policing in Schools: a Canadian perspective,” Gender and Education (2017): 1-20.

5 Wayne Martino, “Boys’ Underachievement: Which boys are we talking about?” Ontario Ministry of Education (April 2008). www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/literacynumeracy/inspire/research/Martino.pdf

6 Elizabeth J. Meyer, “Lessons from Jubran: Reducing school board liability in cases of student harassment” (British Columbia Teachers’ Federation, 2006). https://bctf.ca/uploadedFiles/Social_Justice/Issues/Homophobia/JubranCAPSLEPaper.pdf.

7 Lee Airton, “From Sexuality (Gender) to Gender (Sexuality): The aims of anti-homophobia education,” Sex Education 9, no. 2 (2009): 129-139.

8 Karin A. Martin and Emily Kazyak, “Hetero-romantic Love and Heterosexiness in Children’s G-rated Films,” Gender & Society 23, no. 3 (2009): 315-336.