Learning from the Inside Out

A new approach to learning disabilities

I heard the bells ringing and saw the children running towards the door. There was something terrifying about walking into this class. We were nicely dressed in our uniforms; my hair was done, my tie neatly knotted in a Windsor knot and I looked like I fitted in. It was my first day of school in England. I had moved from Canada to Birmingham and everything was new – the uniform, the people, the accents, and my house. However, one thing remained the same: the ever-nagging questions. “What do I do when she asks me to read?” “What will I do if I have to spell?” I could not hint that school was going to be a problem; at the age of nine I was learning about who I could trust in the classroom and who I could not. Some days I could not even sound out the words, some days the words moved around, and on others I was too tired to even try. I had to make friends with better brains than mine. So began my journey from the inside out…

Nearly 30 years later, on the other side of the world, I completed my dissertation work for Walden University at a small children’s home on the north side of the island of Mindanao, Philippines, where I was introduced to a unique group of children. I had hypothesized that the longer the children were in care and the more exposure to trauma they had, the lower their academic achievement would be. However, I was surprised to find that, in fact, it did not matter how long the children had been in care or how much trauma they had sustained – they all achieved 70 percent or above. Quite remarkable! What was different about this place, these children, these teachers and caregivers? The key difference was that these children were not adopted or discharged at 18, but rather could stay in the home right through university.

Both my own experience and that of the children in Mindanao had three things in common:

- secure attachment (despite attachment injuries)

- optimal learning environments to retrain the brain (I achieved this through after-school tutoring; in Mindanao, the children had a school program within their home.)

- a stable community (For me this was a consistent, loving two-parent home; the Mindanao children experienced this through a program that never gave up on them.)

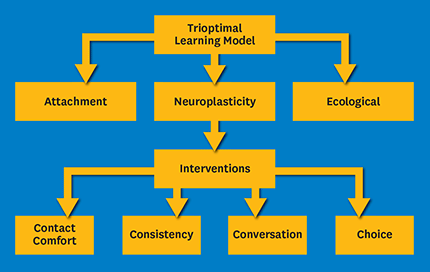

Identifying these three factors led me to the creation of the TriOptimal Learning Model.™

The TriOptimal Learning Model™

The TriOptimal Learning Model™ is a comprehensive approach to providing all learners with the opportunity to excel in the classroom, graduate high school, and become successful members of society. It is built around the following three concepts:

1. Attachment

Early childhood attachment and adult attachment are important factors in the development of secure bonds, both with caregivers and with our romantic partners. The model insists that the teacher/social worker/caregiver look at their own attachment experiences, begin to understand their own attachment style, and learn how it impacts the relationship that they are having with children. While the importance of relationship in education has been acknowledged for decades, we go one step beyond relationship to look at how adult attachment impacts student learning. One teacher told me, “This is completely different. In 25 years of teaching I have never stopped to think about how my desire to be conflict avoidant has influenced how I deal with students who have misbehaved in the classroom.”

2. Retraining the brain: neuroplasticity

A 16-year-old girl asked to speak to me one afternoon. She started to cry as she showed me her math test. She had scored 100 percent. She said that it was the first time that she had felt smart in school. She thanked me for training her brain differently and helping her to see that her brain could learn.

Neuroplasticity is the brain’s capacity to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections over the lifespan. The more opportunity students are given to receive, pattern, and consciously manipulate new information, the greater the stimulation and regeneration of brain pathways.1 I remember the first book I read at the end of Grade 9: To Kill a Mockingbird. It took me three times as long as the others but I read it. I read it by myself. My brain was beginning to regenerate the language pathways in my brain.

3. Ecological systems theory

Systems theory is the third pillar of our model. The more connected the systems (community, government, friends and family) are in surrounding a child with a learning disability, the better chance there is for an optimal learning environment to occur and for children to overcome their disadvantages. For example, when children come into my practice they often have no one left who believes they can succeed. We try to bring that belief back. We tell the child, teacher, and parent that we are going to believe in the child for them until they are able once again to believe. As children see others believing in them, their confidence soars and they are able to achieve so much more than was ever expected of them.

Each pillar of the model is needed in order to create the optimal environment for learning.2 Training is very important, because this is not just a new strategy or technique to be done to or with a child. This is a philosophical shift – first in how caregivers/teachers understand their own attachment traits; second, in believing that the child’s brain can change; and lastly in building a relational system from the individual through to the government level that believes in the child’s right to be securely attached in the classroom. Although we know that we can’t effect change in the whole system, we recognize that every single interaction with a child can slowly build change.

Pilot project and research

Glencorse Family Therapy Inc. opened the first TriOptimal Learning Community in March 2016, in Calgary, Alberta. This is an after-school program (four to eight p.m.) that matches children and teens experiencing learning struggles with an educational coach and social/emotional coach, who work with the children to improve their educational outcomes. The coupling of social/emotional and educational support, facilitated by both a therapist and teachers, is what makes TriOptimal communities different from traditional tutoring programs. We have seen preliminary improvements in the areas of math, reading and writing, but more importantly in self-efficacy and executive functions (working memory, behaviour control and initiation of task). My favourite comment is from a Grade 9 student, who said, “The TriOptimal Community has given me a reason to try.” His mother says that they no longer have to fight with him to do his homework.

Research is underway to follow youth in this program and track their achievement progress. More research is needed in order to determine the long-term efficacy of the model in a variety of contexts as we continue to strengthen and improve its implementation. We hope for opportunities to bring the TriOptimal Learning Model™ to more schools, residential treatment programs, and social programs for youth and children in Canada and internationally.

I was told in Grade 9 that I should apply for a job in a fast food restaurant, as that was the best I could hope for in employment without being able to read. Instead, my parents worked hard to ensure that I got the support I needed to retrain my brain. Now it is my turn to ensure that children with learning struggles – who can become our most marginalized and left-behind students – will be able to challenge the curriculum and graduate with their classes.

For more information

TriOptimal Learning Communities can be built in any school or community. On-site training, site licenses and online support and consultation are offered. http://trioptimallearningmodel.com

En Bref : Ayant surmonté des troubles d’apprentissage et rédigé une thèse sur une maison d’enfants dans les Philippines, Heather Macdonald a puisé dans sa propre expérience pour élaborer le modèle d’apprentissage tri-optimal (TriOptimal Learning ModelMD). Le programme vise à aider les enfants et les jeunes à surmonter des difficultés d’apprentissage en utilisant trois soutiens essentiels : 1) un lien sécurisant; 2) la possibilité de reprogrammer le cerveau en traçant de nouvelles voies neuronales; 3) un environnement multidimensionnel manifestant la confiance dans le potentiel de l’élève.

Chart: Dave Donald

First published in Education Canada, June 2017