Four Literacies for Responsible Global Citizenship

A framework for global citizenship education

In recent years, because of globalization, the world has become increasingly small and interdependent. No longer confined by place of birth or residence, citizens have a collective responsibility to participate in a globalized society.

In 2015, the UN General Assembly recognized this responsibility by adopting the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The resolution includes 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that seek to promote far-reaching social, health, environmental, and political change.

At the same time, several Canadian ministries of education have stressed the importance of integrating the UN SDGs and contemporary world issues into the curriculum as part of a field of study known as global citizenship education (GCE). As a discipline, GCE aims to provide students with the knowledge, skills, and values to address critical global challenges. These include the alarming spread of misinformation, a global health crisis, climate change, and a growing threat to the liberal international order. While some provinces have incorporated GCE into their curricula, most do not offer it as a stand-alone course.

More Canadian ministries of education should adopt a required half-year course at the secondary level on responsible global citizenship. They should seek to equip students with critical thinking skills, including media and information literacy (the ability to find and evaluate information), health literacy (the ability to make informed health decisions), ecological literacy (the ability to identify and take action on environmental issues), and democratic literacy (the ability to understand and participate in civic affairs). Various stakeholders have a vested interest, including school administrators, teachers, curriculum writers, policymakers, scholars, and professors.

Responsible global citizenship

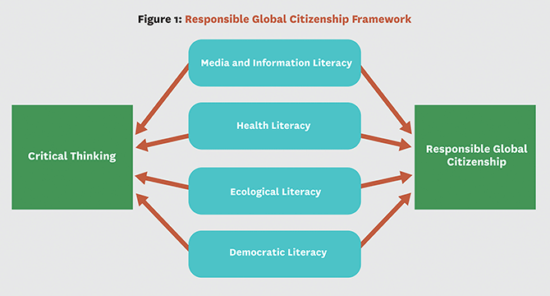

The conceptual framework below (Figure 1) ties responsible global citizenship to critical thinking through four literacies:

- media and information literacy

- health literacy

- ecological literacy

- democratic literacy

As the framework reflects, critical thinking is a necessary skill to achieve responsible global citizenship. The UNESCO International Bureau of Education (IBE) (2013) defines critical thinking as a “process that involves asking appropriate questions, gathering and creatively sorting through relevant information, relating new information to existing knowledge, re-examining beliefs and assumptions, reasoning logically, and drawing reliable and trustworthy conclusions” (p. 15). Critical thinking skills help global citizens make responsible choices when consuming information about the media, health, environment, and democracy. These skills are necessary to evaluate the abundance of information (and misinformation) in the digital age. They also play a central role in making evidence-based health decisions, provide a foundation for exploring today’s complex and interdependent ecosystem, and encourage the kind of civic engagement and participation needed to preserve a functioning democracy.

Media and information literacy

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, Canadians have spent more time on the internet and their smartphones. A recent survey found that 98 percent of Canadians aged 15 to 24 years old use the internet (Statistics Canada, 2021). The survey also noted that 71 percent also check their smartphone, at a minimum, every half hour (Statistics Canada, 2021).

While Canadian youth have unprecedented access to knowledge and information, they are at the same time exposed to more misinformation and disinformation than at any other time in history. This makes it even more critical that students receive media and information literacy training at an early age.

Several organizations, including UNESCO, have taken notice. A decade after publishing the first edition of its media and information literacy curriculum, UNESCO (2021) released Think Critically, Click Wisely: Media and information literate citizens. The more-than-400-page document provides a curriculum and competency framework, along with modules divided into separate units. It also includes useful pedagogical approaches and strategies for teachers.

Meanwhile, in Canada, other organizations (e.g. the Association for Media Literacy, the Canadian Association of Media Education Organizations, and MediaSmarts) have promoted media and information literacy instruction. And for more than three decades, Canadian provinces and territories have incorporated such content into their curriculum. However, as the only Western nation without a federal department of education, Canada has a media and information literacy curriculum that varies by province and territory.

This moment requires increased focus and attention to help Canadian students learn how to think critically when evaluating the media and its information sources and distinguishing between fact and fiction while using information tools. As such, ministries of education should consider adding the following topics in the proposed media and information literacy unit:

- introduction to the media landscape, research process, and critical thinking

- print media versus digital media

- navigating through misinformation and disinformation

- the ethical use of information.

Health literacy

The COVID-19 pandemic is shining a light on the importance of health literacy. The Public Health Agency of Canada defines it as the “ability to access, understand, evaluate and communicate information as a way to promote, maintain and improve health in a variety of settings across the life-course” (Rootman & Gordon-El-Bihbety, 2008, p. 11). This form of literacy requires both knowledge and competence in health-related disciplines.

It should come as no surprise that Canadians lacking health literacy skills are less likely to retrieve reliable information or make informed choices. In fact, limited health literacy (or health illiteracy) can directly impact whether individuals comply with data-driven public health guidance. What’s more, the rapid dissemination of COVID-19 misinformation has placed them at an even greater health risk.

At an organizational level, public health agencies have struggled to manage the current “infodemic” (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2021). In a Public Policy Forum report, University of Toronto professors Eric Merkley and Peter Loewen (2021) provide five recommendations, including to:

- “track misinformation and debunk when needed”

- emphasize “accuracy-focused messaging”

- use “targeted persuasion focusing on downstream behaviours”

- “build relationships with trusted community leaders”

- “start early” (pp. 22–23).

Additionally, medical professionals should provide up-to-date, credible information to large audiences through a strong social media presence.

At the school and board level, teachers and administrators should promote more health literacy instruction. While the concept of health-promoting schools dates back nearly three decades, there is an even greater imperative for students today. In fact, the World Health Organization and UNESCO (2021) recently proposed a whole-school approach to encourage student health and well-being, ranging from school policies and resources to a greater focus on community partnerships and a positive social-emotional environment.

Adopting these standards will help to facilitate cooperation among ministries of education, schools, and civil society organizations. Accordingly, a health literacy unit should include:

- introduction to personal and organizational health literacy

- navigating and evaluating online health information

- responsible and shared decision-making on health and well-being

- pandemic prevention/preparedness.

Ecological literacy

Being a responsible global citizen also requires ecological literacy – defined as “a way of thinking about the world in terms of its interdependent natural and human systems, including a consideration of the consequences of human actions and interactions within the natural context” (Manitoba Education and Training, 2017, p. 15). On top of the combined infodemic-pandemic, an ecological crisis continues to deteriorate. Earlier this year, the federal government released a 768-page document (Health of Canadians in a Changing Climate: Advancing our knowledge for action) that examines the serious threat climate change poses to Canadians’ health (Berry & Schnitter, 2022). The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2021) report, in particular, details the negative impact of greenhouse gas emissions, which is causing increasing temperatures and frequent natural disasters. Additionally, more than half of the world’s key biodiversity areas remain unprotected while pollution levels keep rising (UN, 2021).

A recent poll conducted by Ipsos (2021), in collaboration with the Canadian Youth Alliance for Climate Action (CYACA), examined the views of young Canadians 18 to 29 years old on climate change. The study found that Canadian youth consider climate change to be a top-five issue of concern after housing, COVID-19, health care, and unemployment. Upon reviewing each province’s secondary school science curriculum, sustainability researchers Seth Wynes and Kimberly Nicholas (2019) conclude that there is insufficient focus on scientific consensus, impacts, or solutions to climate change. Government leaders may be more likely to fulfill their climate action promises if Canada does more to develop responsible environmental citizens through climate change education.

Ecological literacy, however, is not limited to climate change education and will require students to acquire skills and competencies in other areas. In addition to climate change, this unit should include:

- environmental ethics

- responsible consumption and production

- energy conservation.

Democratic literacy

The COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on the Canadian way of life has contributed to the discontent many feel. According to a Pew Research Center survey, while only 29 percent of Canadians at the beginning of the pandemic believed the country was more divided than before the outbreak, 61 percent held that view by the following year (Wike & Fetterolf, 2021).

Pandemic fatigue, however, should not serve as an excuse for undermining democratic institutions and norms. Indeed, in the latest edition of The Economist Intelligence Unit’s (2022) Democracy Index (global democracy rankings), Canada dropped seven spots (5th to 12th place). The report highlights a troubling trend – one in which Canadian citizens express an increasing level of support for non-democratic ideas and values.

Civically literate citizens are more likely to understand the inner workings of the democracy and participate through voting, peaceful assembly, or other forms of engagement (The Samara Centre for Democracy, 2019). The Samara Centre for Democracy (2019) report explains that civic literacy can be developed during the Canadian citizenship process, at home, in schools, and outside the classroom. Schools are a particularly important forum through which Canadian youth can learn about civic participation and engagement.

In a civics unit, students should have the opportunity to hear diverse perspectives, make informed opinions, and actively participate in the community. Democratic literacy content should include a discussion on:

- liberal democratic governance and values

- civic rights and responsibilities

- civic engagement and participation

- challenges to the liberal democratic order (e.g. the rise of populism, authoritarianism).

As teachers prepare students for a post-pandemic world, a one-size-fits-all approach cannot address the needs of every student. Yet, there should be a common framework.

The responsible global citizenship framework can serve to guide ministries of education seeking to implement practical and relevant GCE-related courses and content. To develop responsible global citizens and critical thinkers requires the advancement of media and information, health, ecological, and democratic literacies. These four literacies are critical for Canada’s future success and relevance in a global society.

Illustration: iStock

First published in Education Canada, September 2022

References

Berry, P., & Schnitter, R. (Eds.). (2022). Health of Canadians in a changing climate: Advancing our knowledge for action. Health Canada. https://changingclimate.ca/site/assets/uploads/sites/5/2022/02/CCHA-REPORT-EN.pdf

The Economist Intelligence Unit. (2022). Democracy index 2021: The China challenge. www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-2021

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2021). Climate change 2021: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University. www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/

Ipsos. (2021). Young Canadians’ attitudes on climate change. www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2021-10/CYACA%20Report%2020211004_0.pdf

Manitoba Education and Training. (2017). Grade 12 Global Issues: Citizenship and Sustainability.

https://www.edu.gov.mb.ca/k12/

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2021). A vision to transform Canada’s public health system. Government of Canada. www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/state-public-health-canada-2021/cpho-report-eng.pdf

Rootman, I., & Gordon-El-Bihbety, D. (2008). A vision for a health literate Canada: Report of the expert panel on health literacy. Canadian Public Health Association. https://swselfmanagement.ca/uploads/ResourceDocuments/CPHA%20(2008)%20A%20Vision%20for%20a%20Health%20Literate%20Canada.pdf

The Samara Centre for Democracy. (2019). Investing in Canadians’ civic literacy: An answer to fake news and disinformation. www.samaracanada.com/docs/default-source/reports/investing-in-canadians-civic-literacy-by-the-samara-centre-for-democracy.pdf?sfvrsn=66f2072f_4

Statistics Canada. (2021). Canadian Internet use survey, 2020. www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/daily-quotidien/210622/dq210622b-eng.pdf?st=O5mYsIgz

United Nations. (2021). The sustainable development goals report 2021. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2021/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2021.pdf

UNESCO. (2021). Think critically, click wisely: Media and information literate citizens. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000377068

UNESCO-IBE. (2013). IBE glossary of curriculum terminology. www.ibe.unesco.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Publications/IBE_GlossaryCurriculumTerminology2013_eng.pdf

Wike, R., & Fetterolf, J. (2021). Global public opinion in an era of democratic anxiety. Pew Research Center. www.pewresearch.org/global/2021/12/07/global-public-opinion-in-an-era-of-democratic-anxiety

World Health Organization & UNESCO. (2021). Making every school a health-promoting school: Implementation guidance. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000377941

Wynes, S., & Nicholas, K. A. (2019). Climate science curricula in Canadian secondary schools focus on human warming, not scientific consensus, impacts or solutions. PLoS ONE, 14(7), e0218305. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218305